1127 Connecticut Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20036

Originalism

November 14 — 16, 2019The 2019 National Lawyers Convention will take place on Thursday, November 14 through Saturday, November 16 at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C. For over three days, the convention will feature four Showcase Sessions discussing the Convention Theme of Originalism, sixteen breakout sessions sponsored by the Practice Groups, the Twelfth Annual Rosenkranz Debate, the Nineteenth Annual Barbara K. Olson Memorial Lecture, and the 2019 Antonin Scalia Memorial Dinner. Register now!

2019 Antonin Scalia Memorial Dinner

With:

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Hon. Brett M. Kavanaugh

Associate Justice,

Supreme Court of the United States

Union Station

50 Massachusetts Avenue NE

Washington, DC 20002

Thursday, November 14, 2019

Reception - 6:00 p.m.

Dinner - 7:00 p.m.

(ticketed event) BLACK TIE OPTIONAL

SOLD OUT

Nineteenth Annual Barbara K. Olson Memorial Lecture

Featuring:

Hon. William P. Barr

The Mayflower Hotel

1127 Connecticut Avenue NW

Friday, November 15, 2019

5:00 p.m.

(ticketed event)

SOLD OUT

Twelfth Annual Rosenkranz Debate

RESOLVED: The free exercise clause guarantees a constitutional right of religious exemption from general laws when such an exemption would not endanger public peace and good order.

Featuring:

The Mayflower Hotel

1127 Connecticut Avenue NW

Saturday, November 16, 2019

12:30 p.m.

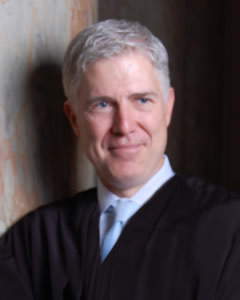

Address by

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Hon. Neil M. Gorsuch

Associate Justice,

Supreme Court of the United States

The Mayflower Hotel

1127 Connecticut Avenue NW

Saturday, November 16, 2019

4:30 p.m.

Showcase Sessions Discussing the Convention Theme:

"Originalism"

Practice Group Breakout Sessions

Up to 20 hours of Continuing Legal Education (CLE) credits available. Direct all CLE inquiries to the Federalist Society's national office - (202) 822-8138 or email [email protected].

The Mayflower has sold out of all available rooms in the reserved room block at our contracted rate of $279. There may still be rooms available at the hotel's prevailing rate, but otherwise we suggest registrants look into other area hotels.

Reserve early! Washington, DC hotels are becoming booked very quickly for the fall convention season. To reserve overnight accommodations for the Convention, please contact The Mayflower directly:

The Mayflower Hotel

1127 Connecticut Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20036

Reservations Toll Free: 877-212-5752

Reservations Local Phone: 202-347-3000

Reservation Link: https://book.passkey.com/event/49941504/owner/1261/home

Cut off Date: October 21, unless rooms sell out sooner.

Inquire about the special rate of $279 per night offered to Federalist Society Convention registrants. Specify "Federalist Society" when contacting the Mayflower. All rooms at this rate are now sold out.

| Sessions Package* | |

| Private Sector Non-Member | $575 |

| Private Sector Active Member | $450 |

| Student/Non-Profit/Government Non-Member | $350 |

| Student/Non-Profit/Government Active Member | $250 |

*The Sessions Package includes all three days of sessions, CLE, and lunches as well as the Annual Rosenkranz Debate & Luncheon.

| Individual Day** | |

| Non-Member | $250 per day |

| Active Member | $200 per day |

| Student Non-Member | $60 per day |

| Student Active Member | $50 per day |

**Individual day purchase includes that day’s sessions, CLE and lunch. It does not include social events.

| Social Events*** | |

| Antonin Scalia Memorial Dinner Non-Member | SOLD OUT $250 |

| Antonin Scalia Memorial Dinner Active Member | SOLD OUT $200 |

| Barbara K. Olson Memorial Lecture & Reception Non-Member | SOLD OUT $150 |

| Barbara K. Olson Memorial Lecture & Reception Active Member | SOLD OUT $100 |

***The social events are now sold out. You may add yourself to the waitlists for the Antonin Scalia Memorial Dinner and the Olson Lecture & Reception. If a spot opens up, you will be contacted and confirmed before any payment is processed.

CANCELLATION FEE OF $100 AFTER MONDAY, NOVEMBER 4.

NO REFUNDS WILL BE GIVEN AFTER MONDAY, NOVEMBER 11.

Media inquiries should go to Peter Robbio at [email protected].

Back to top

2019 National Lawyers Convention

| Topics: | Federalism • Federalist Society • Separation of Powers • State Courts • State Governments • Supreme Court • Federalism & Separation of Powers |

|---|

On November 14, 2019, The Federalist Society opened its 2019 National Lawyers Convention at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, DC with a speech by Governor Ron DeSantis (FL). Governor DeSantis focused his remarks on the Florida Supreme Court and the balance of powers in the federal government.

*******

As always, the Federalist Society takes no particular legal or public policy positions. All opinions expressed are those of the speakers.

Featuring:

Leonard Leo: Once again, good morning. It's my privilege to welcome all of you to this year's National Convention of The Federalist Society. As in years past, the next several days will be a great opportunity to visit with old friends and to make some new ones and, in the Society's long-standing tradition of more than 35 years, to witness all sorts of thoughtful discussion and spirited debates about the current state of our legal culture.

Now this year, we decided to do something a little different: build the theme of the Convention around originalism.

[Laughter]

Now, before you head for the backdoors for another cup of coffee, let me offer two reasons why this evergreen subject is worth exploring here and now and again. First, hard as it may seem to believe, it's been almost four years since the most prominent champion of originalism, Antonin Scalia, passed away unexpectedly.

Since then, there has been ample opportunity for many to feign the mantle of originalism. It's very fashionable these days to talk a high game in terms of embracing originalism, but anyone who followed Justice Scalia's lifelong refinement and defense of this doctrine knows that this is tough and tricky work. Simply saying you're an originalist doesn't make it so. And this Convention's sessions will hopefully define the area more precisely.

The second point I would make is that the broader public needs to understand why some stand up for originalism. Justice Scalia always believed it's because originalism's preservation of the structural constitution is the best means to protecting the individual worth and dignity of every human person, which are at greatest risk when structural limitations on government powers are not respected and enforced. And I suspect there will be some discussion of this as well over the next couple of days.

But before we embark on the panel discussion that addresses the specifics of originalism, we're going to open the conversation with remarks by someone who has long been an adherent of the originalist enterprise, going all the way back to his days as an active member of the Harvard Law School Federalist Society.

Today, he's putting originalism in action as Florida's 46th Governor, just recently appointing two justices to the Florida Supreme Court through a process that placed great emphasis on perspective candidates' fidelity to originalism and textualism and other aspects of the proper judicial role. He'll soon be at it again because President Trump quickly stole his two appointments to the Florida Supreme Court, soon creating another search for committed Floridian originalists.

Please join me in welcoming an individual with an extraordinary record of dedicated public as well as military service, Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida.

Hon. Ron DeSantis: Thank you. Thanks, Leonard. Thank you, guys. Thanks so much. Great to be with you. I get to come back in Washington. I'm a recovering Congressman, and so people will ask me, "Are you happy to be out of D.C.?" And I say, "Is the Pope Catholic?" Of course, I'm happy to be out of D.C. And my swamp is warmer right now than your swamp is; it's about 75 degrees in Palm Beach, so—but it's good to be here.

One of the reasons I ran for governor is because we had three pending vacancies because of age restrictions on our state supreme court. There had been a lot of, I think, positive things that had happened in Florida with respect to limited government, school choice, all these things, but one of the thorns in the side had been you still had an activist majority on the state supreme court who would rewrite laws, rewrite the Constitution, and basically showed very little respect for the political branches.

And that was something that I think was not only was -- I think that was bad for the constitutional system in Florida, but I think it was also bad for some of the things we were trying to do in terms of economic growth because you really didn't have a lot of certainty. The legislature could pass reforms, and they'd be uprooted pretty quickly.

So we had a seven member court, four justice majority, but three of those four were effectively termed out. And so I came in and was able to do, actually, three appointments within my first few weeks of office. Now, in Florida, the way this works is not like it is with federal judicial confirmations. We use what's called a judicial-nominating commission. And so this is actually, I think, still during the governor gubernatorial election where they opened applications because they knew there were these three vacancies would be there so people could apply. The Commission goes through it. I think they interview everybody that applies and then they whittle it down to a certified list.

So they had a certified list that was done sometime in December during the gubernatorial transition given to me. And all you do in Florida at that point is just pick the names, and they're on the court. Sign their documents and they're on. There's no Senate confirmation, no anything beyond that. And so this was something that I took very seriously.

So we had all eleven people came down to Florida. I had a group of people that I trusted, Leonard was one of them. And I wasn't involved at this point. And they just interviewed everyone, gave me an assessment, and then I personally interviewed all 11 one-on-one. And then determined -- so this is some time, probably, in like mid-December, and then at that point, I figured okay, I think I have my three people.

But I didn't tell anyone who I picked, because I knew it would leak and it was a situation where if I were to announce it before I took office, we were just coming off the Kavanaugh thing. I didn't want them to be pinatas and just get attacked or whatever. Once I was in, I could sign it, they’re on the court, and that's just kind of the way it was.

So I didn't tell anyone because I just didn't want it to leak. And my wife even told me, "Just don't tell me." She's like, “I don't want to know what it is.” I'm like, "Okay." So we had it. You know, you're going on. You're doing whatever you need to do to put people at the head of agencies, all these other things, have an agenda, come out of the gate very quickly. So there's a whole bunch of other stuff happening. So we end up going in. I'm inaugurated January 8. You know, you go, you take an oath. You give the speech, whatever. And then you have an inaugural ball.

Well, we did all this stuff. Actually, my son at the time, we baptized him in the governor's mansion right after the swearing in, which was special. So my wife's getting ready for the inaugural ball. I am just sitting in the mansion wondering how did I get here type of deal. But then it dawned on me that the next morning, I was supposed to announce my first Supreme Court pick, but I still had not told anybody who I was going to pick, including the nominee herself.

[Laughter]

And I think she's here, but Justice Lagoa, who as Leonard mentioned, was one of the justices from our Supreme Court who's gotten tapped to be on the Eleventh Circuit and will be confirmed, I think, by the full Senate very quickly, but -- so I called Barbara like 5:30 the day before and said look, if you can show up in Miami at 10 AM tomorrow, I'll put you on the Supreme Court.

[Laughter]

And she did. And she gave a great speech, but she was up late because I did not give her a lot of lead time on that one. So we ended up doing it and then we put two other great justices on the court. One of which, Robert Luck, is also nominated for the Eleventh Circuit. So they will have been on the Supreme Court less than a year, about 11 months. And then they will go up to the Eleventh Circuit, which is well-deserved, and I think those circuit courts are very, very important.

So this was important for Florida. I think that we are on a good path. But I think that it was -- obviously, I took it seriously. But you had a lot of people working through Florida for a long time to develop a really good bench of legal talent. I think we've got a lot of great people. And so as good as Barbara and Bobby Luck have been, I don't know if I'll quite get to that level, but we'll get pretty close because we got a lot of really good people to choose from. So within thirteen months, most likely, because our process now for these remaining two will probably go to February, I will have made five appointments in 13 months

And to put that in perspective, two of my predecessors, Jeb Bush and Rick Scott served a combined 16 years, and they made a combined three appointments in 16 years. So sometimes these things just happen, so I think it's neat. And I also -- obviously, here in Washington, one of the great success stories of the Trump administration has been their federal judicial appointments. You have two, of course, Supreme Court justices and a really fast clip of confirming circuit courts of appeals judges, which many of you know is sometimes just as important given the small caseload of the Supreme Court. And I think that's a great accomplishment for the President.

I think Senators like McConnell and Grassley and Lindsey Graham deserve a lot, a lot of credit for that. And I think there's been an emphasis on finding judges who feel that originalism and textualist approach is the right way to do it. The reason why I think that's the right way to do it is because you have to have some objective measure to go by. It can't just be flying off the seat of your pants, philosophizing and imposing whatever idiosyncratic views you have on society under the guise of constitutional interpretation. So originalism provides a mechanism to cabin judicial discretion, which I think is very, very important.

And one of the frustrations I had in the Congress was I think the Founders were pretty clear about how the constitutional system was arranged and would operate. They viewed -- you had three separate branches. One branch was not necessarily subordinate to the other so when they say they were equal, in that sense they were. But they certainly were not equal in terms of the powers that were assigned to the branches.

There was qualitative and quantitative differences between the branches. Clearly, they believed -- Madison said the legislative authority predominates in a republican system of government. If you look at the powers assigned in Article I of the Constitution, the power of the purse, so the Executive can do what they want. You take away the money, the Executive can't do it.

So the Congress had robust powers, and I think the Founders viewed the Congress as the focal point in constitutional government. They thought the Executive would have an important role, but that would really depend on the exigencies. Obviously, if you're engaging in any type of military conflict, President's Commander in Chief in foreign affairs, President had a very, very important role. But ultimately, even though the president could veto acts, the legislature could check that veto by overriding the veto.

And so the President was important, but they also had just rebelled against the king, and so they did not envision the Executive as it is today with the massive bureaucracy. And then, of course, they thought the courts were important, but as Hamilton said by far the weakest of the three branches because it could exercise neither force nor will but merely judgment. It ultimately depends on the Executive to enforce its judgments. And so that was, I think, their view, so the Court would play a role, but it would not be the dominant role in the constitutional system.

Well, I think today, as we looked and having served in the Congress, to me, Congress is by far the weakest of the three branches. If you look, its most robust power, the power of the purse, it effectively has just put on autopilot by -- a lot of the spending is just automatic anyways. And then the rest, they use continuing resolutions to just basically perpetuate government and perpetuate the status quo.

Very rarely are they actually using the power of the purse to discipline the Executive Branch, to reign in any type of Executive overreach. And that is true regardless of who's in which party or the other has been in. And so you have a really neutered, I think, Legislative Branch. I mean, really, I did more in one week as governor than I did in six years as Con -- and I was active. I worked hard. I just -- they don't use the authority they have in an effective way and I think that the constitutional system is discombobulated as a result.

Of course, the Executive Branch, when you look at what the President's able to do, some of that is just because different circumstances. We're more involved internationally than we were when the Founders envisioned the Constitution. So there's a huge power there but also the bureaucracy.

Most of the people that would come to see me when I was in Congress and had a problem with something with the federal government, did not have a problem with anything we were actually passing in Congress. It was the agencies that were doing this or doing that, and so most of the lawmaking was really being done by the Executive Branch agencies. And so you've had a massive bureaucracy grow, and you have the Executive function really exercising both legislative and in some cases judicial powers, which is obviously not something the Founders would've wanted to do.

And then you have the Court which in some respects -- in some instances, I think, sees itself as being almost superior to the other branches and superior to the Constitution itself even and has gotten involved in a whole host of different things that I think they probably had no jurisdiction to deal with in the beginning. But certainly, the Court has more of an impact than the Congress does day in and day out, even only accepting 80 cases a year.

So that's kind of the system, and so it just caused me to reflect. I think it's great that you have two Supreme Court justices here and all these circuit judges. But the fact that that is viewed as a major achievement, to me, suggests that the courts are exercising too much power in the first place.

You go back and look at --

[Applause]

You go back and look at some of the past -- I think Joseph Story when Madison put him -- nominated -- I think he was confirmed within five days. You look at Stephen Field, during the Civil War, he's a Democrat from California. Lincoln nominates him. Within a week, he's confirmed. Robert Jackson, right before World War II, FDR. And the Court had started to get more active then, but, still, I think he was confirmed in like three weeks.

And so the fact that now we have all these titantic struggles about who sits on that shows that the Court is playing too big a role in our society. And there's some that say well, if we just get enough originalists on the court, then -- on the Supreme Court and the lower courts, then everything can be made right and everything will be good. And I think look, that would be beneficial, don't get me wrong. But I have to think back to Federalist 51.

The whole premise of the system is you're not going to have the right people in the positions of power. That's why they designed the system the way they did because they said, “If angels were to govern men, then no government would be necessary.” And that is something that I think they believed at -- the Founders believed at their core, that you had to have a system of checks and balances to keep each branch in line.

And so, for me, I want to see great judges, I think that's important. But I also want to see a system that works even when you have the wrong people in positions of power. And I think that we see some of the problems here, so I think judicial powers is too robust right now. And I think the checks upon it are just simply inadequate. I think part of it is you can go back to the original design and see the checks on it. But then also the checks that are there really aren't used by the Congress anymore. And I think that one of the areas—and I'm sure you guys will discuss it at this conference—that brings us into focus is the use of these nationwide injunctions by one district judge.

And so you have a national policy that's put in place by the Executive Branch, and then you have a flurry of lawsuits. So the Executive wins in Boston. They win in New York. They win in Atlanta. They win in Minneapolis. They win in Las Vegas, but they lose in San Francisco. And so guess what? You win all those other ones, you lose in San Francisco, so the whole policy is put on ice.

And we can sit there and say oh yeah, these are just rogue districts judges. They're part of the legal resistance. They're resisting Trump and all this stuff. And the Supreme Court will correct it. They have corrected a lot of these. And that is true, but what happens in the meantime? You got two years that goes by where the policy is frozen just because you have one district judge that puts it on hold?

To me, one district judge issuing a nationwide injunction is not a legitimate use of judicial power. I'd like to see the U.S. Supreme Court reign that in, but I think there's things that probably Congress can do to reign it in. But that's just the thing. I think the checks that are there, jurisdiction stripping, hasn't really proven to be that effective. Hamilton said look, if a judge gets off the rails, he'll get impeached and removed from office. That hasn't really proven to be successful.

I think in The Federalist, Hamilton suggests that if the judges get off the rails, then the Executive will just let that decision go but not really enforce it, but again, that's not something that is there. But I think that we're in a situation now where whatever institutional counteraction that the Founders envisioned, that's just simply overwhelmed by the partisan interest that you see now in national politics.

And so there may be something that's detrimental to your branch, but if that's more for your team and the partisanship is going in a good direction, then you're willing to see your own branch diminished in order to achieve the more partisan ends. And that goes with both sides. But I think the Founders believed that where you sit was where you were supposed to stand when it comes to institutional power, but that's not really where it is.

You do not see a robust defense across party lines of Congress's prerogatives, of the Executive's prerogatives, when those prerogatives are challenged. It's all situational. So the Congress really cares about its lawmaking authority when President Obama is doing some of these more legislative-in-nature executive orders. But then the same people that didn't care about that, they now care about it when the president’s different and vice versa. So that, to me, is just not going to be something that's going to be an effective check.

And so I think back -- Lincoln, he had to confront the Dred Scott decision, which is obviously one of the worse cases that the Supreme Court has ever decided, and in his inaugural address, he said that if you have the whole policy of the whole country decided by the Supreme Court based on one lawsuit between two parties, then the people are no longer their own rulers, and they're essentially turning over their authority to this imminent tribunal. And he proceeded to work with Congress.

Dred Scott said you cannot prohibit slavery in the territories. Well, the whole Republican Party was founded to prohibit slavery in the territories. So that's kind of like saying that the Republican Party itself was unconstitutional at the time. And so, Lincoln, they went ahead, and they did ban it in 1862. The Congress did that in spite of Dred Scott. But Lincoln had to wrestle with this before he was president because he says okay, if a decision's made, if we just don't respond, don't honor any decision, then you just have lawlessness. So he always honored it with respect to the parties in the case in Dred Scott, but he said, “I'm just not ready to say that this settles our policy for the whole country infinitum.”

And he went through different factors in his judgment. He believed that a unanimous decision carried more weight than a split decision. I think Dred Scott was 7-2. He said if the decision broke down on party lines, that he'd be less likely to say that that settled policy for the whole country. And then he said if it was a novel interpretation that was at odds with how previous branches had viewed it—so for example, Congress had enacted a lot of legislation that presumed they had the authority to regulate slavery in the territories—that that would be something that he would consider. But, I mean, this was something that he really, really struggled with.

And I don't suggest that there's easy answers to it, but what I would like to suggest is that in our system of government, it's the Constitution that is supreme. It's not the judiciary that is supreme. Courts are part of the constitutional system, but they do not hover above the constitutional system. And the more serious that other political actors take their role, I think the stronger our constitutional system will be.

So, I guess, the point I'll make is originalism, I think, is important to figure out how you do constitutional interpretation, how you apply legislative text. But I think, also, I consider originalism to be the structural Constitution and how different people who are actually in these branches are going to use their authority to preserve their own institutional interest. And if we say originalism is only about interpreting a statute or only about interpreting the Bill of Rights, then I think we're leaving so much on the table.

And, ultimately, even though an originalist judge, I think, would be more respectful of the separation of powers than a non-originalist judge, we're kind of tacitly still saying that the judiciary is superior to the other branches of government. I don't think that's what the Founding Fathers envisioned, and I don't think that that's what's the best for the country.

So members of Congress, if I was still there, I would tell them to take their obligations to protect their institutions seriously and the same thing with the Executive Branch. True originalism means all these branches checking and balancing each other just as the Founding Fathers intended. Thank you very much. Thanks. Appreciate it.

[Applause]

Leonard Leo: Thank you very much, Governor. If everyone could please remain in their seats, and we're just going to call up the panelists for the next session.

2019 National Lawyers Convention

| Topics: | Constitution • Founding Era & History • Philosophy • Supreme Court |

|---|

On November 14, 2019, the Federalist Society hosted a showcase panel for the 2019 National Lawyers Convention at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, DC. The title of the panel was "What is Originalism?"

While originalism is on the rise today, its content has become fractal with different views of what are the methods of determining a constitutional provision's meaning. This panel would look at the many types of originalism and consider the extent to which the theoretical differences will result in different outcomes.

*******

As always, the Federalist Society takes no position on particular legal or public policy issues; all expressions of opinion are those of the speakers.

Featuring:

Hon. Amul Thapar: Good morning, everyone. I want to thank everyone for coming to this event. And we are going to start our panel now. We’re going to have a dramatic entrance by President Wydra, but she’s parking her car. This wonderful D.C. traffic that I don’t miss -- and so she’ll be here momentarily. I’m going to start with an intro.

You may wonder why the moderator is giving the intro. We had a call to plan this, and they unanimously voted that I’d give the intro. In law school, they always said the A students would be professors, the B students would be judges, and the C students would be millionaires.

[Laughter]

And so the A students wanted to hear the B student go first so they could correct all of my misconceptions about originalism. So the name of the panel is “What is Originalism?” And I thought what better to start with than what is originalism? In its most basic form, originalism is the idea that the Constitution’s meaning was fixed at the time of the Founding, and that this meaning constrains judges. There are many strains of originalism. Indeed, many would say for every three originalists, there are four theories of originalism. And you are about to hear six different theories from the A students.

Today, however, many originalists, and especially originalist judges like myself, believe in original public meaning originalism. In practice, when we are doing this inquiry, we are looking at how the people who ratified the words would have understood them since communication needs both a speaker and an audience. After all, to interpret any document, we look at the words of the document.

Think of how communication works in general. To understand what I am saying right now, your mind is interpreting my words as you understand them. If we want to figure out what something meant 100 years ago, we have to look at how people understood the words at the time. Think about a contract between two parties. To understand what the parties meant, we look at how they understood the words at the time. There’s a great law review by Gary Lawson in the front row called “I’m Reading Recipes” that gets to this exact point, and it’s worth reading.

I also believe originalism is compelled by the oath. As a judge -- and here is the dramatic entrance I promised.

[Laughter and applause]

Elizabeth, I said I don’t miss D.C. traffic in Kentucky.

Elizabeth Wydra: It’s terrible.

Hon. Amul Thapar: I also believe originalism is compelled by the oath. And the very first thing you do as a judge is you take an oath. And you should pay attention to the oath. The text of the Oaths Clause in Article 6 supports just that. It says that if we take an oath to this Constitution, it says this being the important word, Constitution, not a constitution of our liking, but this Constitution, again, meaning the words and concepts in the Constitution as ratified and subsequently amended. That is originalism. The Supremacy Clause also uses the word this Constitution. It says this Constitution is supreme and judges are bound by it.

As Randy Barnett says, and I love this saying, “It is the law that governs those who govern us.” In other words, judges and public officials take an oath to this Constitution. Alexander Hamilton made exactly the same point as Professor Barnett in Federalist 27. I think he was kind of reading into the future when he said the Constitution is “the supreme law of the land,” and that “all officers, legislative, executive and judicial will be bound by the sanctity of the oath.”

And the oath is especially important to remember as a judge because as Chief Justice Marshall said, “We have the ultimate say to say what the law is.” And we know all of this because of a more basic point. The Constitution was written, unlike in England. The existence of a written Constitution suggests that we are obligated to follow it. If not, what is the point?

And so now, I will turn to the A students to tell me what I got wrong. And I’ll start with Evan Bernick, who is clerking for the brilliant Judge Sykes.

Evan Bernick: Thank you, Judge. What is originalism? Big question. I spent what was probably an unhealthy amount of time last night trying to formulate a precise and accurate definition that would be uncontroversial. I eventually gave that up and fell asleep and didn’t satisfy myself that I had a definition. So when I woke up this morning, I decided I would set more modest aims for myself. I would say a bunch of things about originalism in general that I believe to be true, some things about my form of originalism that I know to be true, and just see what happens from there. So bear with me.

One way to get a feel for what originalism is is to understand two distinct but related claims that originalists tend to make. The first claim is a descriptive claim: The original meaning of the Constitution is law. The second claim is a normative claim: Public officials ought to follow the original meaning of the Constitution. So if you find yourself in conversation with somebody here today who’s making either or both of these types of claims, you’re probably talking to an originalist. Actually, if you’re talking to anybody in this room today, you’re probably talking to an originalist. That’s a safe assumption.

So what is the original meaning that an originalist says is law? Early originalists tended to talk about the original intentions of the Constitution’s framers. As Judge Thapar pointed out, most originalists today don’t talk that way. They talk about the conventional or public meaning of the Constitution’s text, what a reasonable reader of the Constitution would have understood the various words, phrases, and symbols that make it up to mean at the time that it was ratified. Of course, language is imprecise. Just read Federalist 31. And of course, historical research is hard. It’s not always clear that interpreting constitutional text is going to give you a clear answer to litigated constitutional questions.

So what do you do? Well, originalists disagree. Some originalists argue that originalism’s domain is limited to the interpretation of text, and that whereof originalism cannot speak, it ought to be silent when it comes to the implementation of text. I am not one of these originalists. In my view, following the original law of the Constitution entails not only following the original meaning of the Constitution’s text when it’s clear, its letter, but when it’s not clear, having recourse to the original functions of the Constitution’s text, its original spirit.

So when a public official encounters constitutional unclarity, he should have recourse to the publicly available functions that those who ratified the Constitution into law would have associated with that textual provision at the time it was ratified, and he should formulate a statute, a regulation, or a doctrinal rule that’s designed to implement that text. So there’s the letter, and there’s the spirit.

Now, why should public officials follow either the letter or the spirit of the Constitution? There are a variety of normative arguments for originalism. First is a kind of ontological argument: It follows from the nature of a written Constitution to follow the original meaning of that Constitution. The second is a democratic will or a popular sovereignty type argument: The original meaning of the Constitution expresses the will of the sovereign people, and anything less is undemocratic. The third is kind of a consequentialist argument: Following original meaning will generally lead to results that, all things considered, are better than following some form of non-originalism, whether for the sake of liberty or the rule of law or generalized social welfare.

Picking up on Judge Thapar’s comments, I want to throw one more normative argument into the mix. Originalism equips public officials to fulfill a promissory obligation. Promising is a valuable social institution. Most people think that they ought to keep their promises and that other people ought to keep their promises to them. Every public official makes a promise pursuant to Article 6 of the Constitution to support this Constitution. And there’s no compelling reason to believe that the original public meaning of this Constitution that Judge Thapar has just described differs substantially from the contemporary public meaning of this Constitution that public officials take. You very rarely see public officials claiming that they are bound to support a different Constitution than the one that went into effect in 1788 as validly amended, that they took an oath to a different fundamental entity than did Washington. As a consequence, both the original public meaning of the Constitution and the contemporary public meaning of this Constitution refer to a historically situated document that received its meaning when it was ratified into law.

Now, not all promises carry a significant moral obligation. Think of an assassin’s promise to kill someone. And I’m prepared to say that had we an evil Constitution that required systematic injustice, I’m not necessarily sure that a promissory obligation could be supported on the basis of an oath to follow it. However, we have a reasonably, if imperfectly just Constitution that provides for a scheme of social cooperation that secures the liberty and the welfare of the people who live under it reasonably well, better than any reasonably available alternative. And that’s enough to support a moral obligation on the part of public officials to do as they have promised to ensure that the Constitution delivers on its promises. Originalism equips public officials to discharge that moral obligation.

[Applause]

Hon. Amul Thapar: Thank you. Next, we’ll have Professor Balkin, who is the Knight Professor of Con Law and the First Amendment at Yale Law School.

Prof. Jack Balkin: Hello, everyone. I am delighted to be here. It is nice to see you all. I thought I would tell you a little bit about my own theory of originalism. I guess we’re all going to tell you about our own theories. My theory has different names. Sometimes it’s called framework originalism. Sometimes it’s called living originalism. But I’ll try and explain what this is all about.

So framework originalism; so what’s a constitution for? Well, a constitution like ours is basically serves many functions, but one function it serves is the following: It helps make politics possible. In other words, it helps people to have a framework in which they can struggle over power and whatever else they want through constitutional limits instead of just a free-for-all. So constitutions are designed to make politics possible. And they make politics possible by constraining politics within a framework. And so the idea of framework originalism is to figure out what’s in the framework, and here’s my view. The framework is the original meaning of the words and phrases in the Constitution and the adopter’s choice of rules, standards, and principles. That’s what the framework is.

Now, why do I mention rules, standards, and principles? Very simple. If you and I were going to design a constitution together, we would find that sometimes we wanted hard-edged rules that were very difficult to get around and didn’t take much work to apply. But we would also find, especially if we were designing a Bill of Rights, for example, or some other parts of the Constitution, we’d have to use standards; unreasonable searches and seizures. Sometimes we’d even have to use principles; freedom of speech, freedom of religion. And so if you look at constitutions around the world written after the American Constitution, you’ll see they have a combination of rules, standards, and principles. The framework is the original meaning plus that choice.

And then there are a bunch of other basic principles that you’re very familiar with that are also part of the framework. In the American Constitution, we have separation of powers. We have federalism. We have the rule of law. We have a commitment to democracy and a commitment to a republic; that is, a republican form of government. These things are not always directly stated in text, but they are implicit features of the kind of constitution we have.

Okay. What it means to be an originalist from my perspective is to be faithful to that framework. Now, it turns out that history plays a big role in what it means to be faithful to the framework. History matters in figuring out what the original meaning of the words and phrases is. History matters in deciding whether we have a rule, a standard, or a principle. History matters in deciding what principle we have. And history also matters in the next phase of constitutional interpretation, which is what is sometimes called construction because when you have a constitution that has gaps or silences, or has rules, standards, and principles that require some degree of judgement to basically apply in new situations, you will have to use the text in order to judge.

Now, when the text has a rule, you apply the rule because that’s what the text says. When the text has a standard, you apply the standard because that’s what the text says. When you have a principle, you have to apply the principle because that’s what the text says. But when you apply a principle, sometimes there’s more than one possible answer. That’s why you need construction. Construction is an action of judgement. It requires that you spend time thinking about how best to be faithful to the Constitution.

How do you engage in construction? Well, I could write a whole book on this. In fact, I’m writing one right now. But, very simply, lawyers are not at a loss when they engage in construction. There are a bunch of standard techniques and kinds of arguments that lawyers use, and those are the ones that you’re supposed to use when you engage in construction. You know them all. You make arguments from structure. You make arguments from precedent. You make arguments from custom. You make arguments from convention. You make arguments from the history of the United States and its traditions. You make arguments from the nature of the American Constitution and the nature of the constitutional compact. These are all very familiar arguments. You know them all. If you went to law school, they are basically second nature. This is the task of people who are engaged in construction.

Now, here’s the last idea I want to give you. Mine is also called living originalism, which is a mixture of living constitutionalism and originalism. That may seem very strange to you. You thought they were opposed. No, not at all. In fact, they are two sides of the same coin. But my version of a living constitution is a little different than the version of a living constitution that you may have heard of or thought about.

All I mean by living constitution is this: In each and every generation, it is the obligation of that generation to apply the Constitution’s rules, standards, and principles in their own time based upon the tradition that they have received from the past generations. That is their duty. As they do it, as new laws are passed and as new decisions are rendered, as new constitutional controversies arise, they will be adding to that constitutional tradition. They will be producing something to what they had before. That process of addition, of construction over time is what we should call a living constitution. Understood in that way, there is no contradiction or conflict between the idea of fidelity to original meaning, that is, the framework, and the construction of the Constitution over time, which is the proper way to think about what we have when we talk about a living constitution. Thank you.

[Applause]

Hon. Amul Thapar: Thank you, Professor. Now, we’ll move to Professor John McGinnis, who is the George C. Dix Professor in Constitutional Law at Northwestern University.

Prof. John McGinnis: Well, thanks very much. I’m going to explain what Mike Rappaport, who I write with about these matters, and I think is the best form of originalism, and it’s called original methods originalism. And I can do that, I think, a little bit by contrasting our position with Evan’s and with Jack’s.

First, I don’t agree that it’s an analytic truth that originalists should seek the public meaning of a provision. As Evan notes, some have thought the proper objective interpretation is the intent of the Framers. I don’t think we can decide that question as a matter of contemporary linguistics or philosophy. It depends, crucially, on the methods of interpretation that were expected to be applied at the framing, those original methods.

One colloquial way of, I guess, expressing this is I’m in favor of originalism squared. We not only look for the original meaning, we look for it through those original methods. These methods were key for both positive and normative reasons. Positively, the meaning of a text, particularly a complicated text like the Constitution, must be a function of the methods that were used to decode it. Otherwise, you will get some other meaning. You won’t get the meaning that was fixed at the time where overusing these methods is normatively attractive. After all, it was the meaning as fixed by the applicable interpretive methods that got the supermajority of votes that makes our Constitution fundamental law and likely good law.

And as a matter of historical fact, I do agree that the object of interpretation at the time of the framing was intended to be the public meaning of the document. That’s what the jurists at the time showed they wanted. But it doesn’t follow that the meaning was what a casual reader would have understood it. To the contrary, context is what is essential to meaning. And the most important context for the meaning of the Constitution is its legal context, which implies that the key meaning of it is often its deliberated legal meaning. Sometimes, that meaning coincides with what a layman would ascribe to it, but sometimes it’s supplemented by a meaning that would be completely clear only in a legal context. We understand that in ordinary life where often people say, “Well, I think this is what it means, but really, for a detailed answer, ask a lawyer.”

The centrality of the legal context for the meaning I think is clear from the history and document itself. The Constitution wasn’t created ex nihilo but against a background of legal texts like statutes and, indeed, state constitutions. On its face, the U.S. Constitution declares itself to be law. It was put into final shape by the Committee of Detail. And who was on that Committee of Detail? The greatest lawyers of the convention. It has scores of terms — I’ve counted them — that are obviously legal and hundreds others — I’ve counted those as well — that might be legal, depending on our rules of interpretation.

It even contains provisions that embed legal interpretive rules. One of those is the so-called non obstante legal interpretive rule contained in the Supremacy Clause; anything to the contrary notwithstanding. That rule eliminates another legal rule that might have been applied that favored harmonizing state and federal law, even when they were in tension. Thus, the substantial legal context, legal references, and legal vocabulary of the Constitution all show that it was expected to be interpreted according to the relevant legal interpretive rules of the time.

As a result, I have to say I do disagree with those like Jack who think the Constitution is essentially an open-ended framework to be filled in, often by construction. The view of the Constitution as a general framework was certainly accurate as applied to Britain’s unwritten constitution. But as William Patterson, one of those great lawyers on the Committee of Detail, said the glory of the American Constitution was, quote, “it was reduced to written exactitude and precision.” There’s simply no evidence from the early republic that judges were thought to have a power of construction separate from interpretation. That suggests that they had a rich understanding of what could be gleaned from the words of the Constitution.

And to the question of the work of each generation, the Constitution sets that forward itself. Each generation adds to the Constitution fundamentally through the amendment process. To be sure, the proof that the Constitutional law can be generated mostly by determinate legal meaning is ultimately an empirical one.

But I’d end by noting that we really live in a golden age of originalism. Scholars are continuously finding more precise meaning by looking at clauses that might have been thought to be open-ended and indeterminate like due process, the Eighth Amendment, privileges or immunities, and yes, even unreasonable searches and seizures, and finding that these actually have relatively clear legal rules when understood in the legal context. What they are doing is they are resisting the idea that when clauses are not clear on their face, we go to construction.

Instead, what they’re doing, as I think the interpreters of the Constitution did at the time, they’re choosing the better interpretation based on all the available method, even if that interpretation is only somewhat better than the alternatives. Indeed, I think today, the greatest achievement of originalism is the meticulous unpacking of carefully drawn provisions of the original Constitution and its all-important amendments. Thank you.

[Applause]

Hon. Amul Thapar: Thank you. Next, we’ll go to Professor Sachs, who’s a Professor of Law at the Duke University School of Law to reconcile all of this and give us a theory.

Prof. Stephen Sachs: Sure thing.

[Laughter]

Thank you all very much for taking time out of your Thursday to come hear us in the morning. I’ve seen at least one former student in my originalism seminar, so I apologize to him if some of this is familiar.

Trying to sum up what’s gone thus far and reducing it to some extent to slogan form, I’d say that originalism is following the Founder’s law. Or to have a slightly longer slogan and stealing a page from Chris Green at Mississippi, you could say that America has the oldest continuously operating written constitution in the world, is another way to state originalism, that we have the oldest continuously operating written constitution in the world. If you think that, and many people do, you might be an originalist.

So what do I mean by that? Let’s start at the end: written constitution. We do not have an evolving customary common law tradition that is our Constitution. We are a common law country, we do have common law rules, but we do not have a common law constitution. Instead, our Constitution is an enactment. It’s a legal document that was adopted at a particular time and added some rules to the legal system, and those rules stay as they are until they are lawfully changed.

In order to figure out what the Constitution added, we have to look back at the original law. So if I could add one more level on top of John’s, if he’s going to do originalism squared, I’d say originalism cubed. We used the original law to find out what original methods are properly used to read this original text and find its original meaning. I’m sure we can get up to fourth and fifth powers later on.

Second, originalism says that we have a continuously operating Constitution. The written Constitution, that old one from back then, is still good law. When you’re making a legal argument in the American tradition, you can’t say the way they might say in France, “Well, that was the Fourth Republic. This is the Fifth Republic, and we just do things differently now.” You can’t say, “Well, the Supreme Court went the other way,” or “Well, the New Deal happened.”

Nobody in our system is given legal authority to change the Constitution except in the way the Constitution actually lays out. The Supreme Court can — I know it’s shocking to say — sometimes be wrong on the law. But the Constitution of 1788 can’t be wrong on the law, although it can be amended. That means that you’ve got to have some theory for how you get lawfully from the Founders and the Founder’s law to today. This is a claim not just about how you read the text or how texts have to be read. You can read the Constitution lots of ways. You can read it as a prose poem. You can use it to line a bird cage. It’s about preserving the rules that the Constitution laid down and that remain in force over time. The text is there to preserve whatever rules the text actually made at the time that it was adopted.

And finally, we have the oldest continuously operating written Constitution. We’re looking at a very old document. That means it might turn out sometimes to be bad policy. It might not do the things we want it to do. But while the Constitution might turn out to be bad policy, it can’t, as I said, be wrong on the law. And when we follow the Constitution, we’re not necessarily following it because we think everything it does is good or that everyone who made it was good any more than we follow ERISA because of some sort of patriotic piety toward the Ninety-third Congress and President Gerald Ford. They might have been great, but ERISA is law today because it was enacted and has never been repealed. And that’s how things work for enacted documents in our system.

The same is true of the Constitution. And that’s why if we’re talking emoluments or impeachment or the Take Care Clause or recess appointments, arguments very naturally fall into an originalist register because whatever powers George Washington has, the occupant of the White House has today. Whatever powers Congress had in the First Congress, the current Congress does too. This is the orthodox way of defending legal claims in our system, and that’s what makes originalism our law.

So many of you may have felt already that you were originalists. Some might be surprised to discover that you are originalists, sort of like the character in one of Molière’s plays who is surprised to discover, “Wow, I’ve been speaking prose all my life.” You might have been making originalist arguments all your life and only realize it now because all that originalism is is following the Founder’s law. Thank you.

[Applause]

Hon. Amul Thapar: Next, we’re going to hear from President Wydra. Elizabeth Wydra is the President of the Constitutional Accountability Center, and she’s going to tell us why everyone before her is wrong.

Elizabeth Wydra: [Laughter] Thank you so much, Judge. And thank you so much to everyone for being here this morning. I always enjoy coming to speak to The Federalist Society, in part because of great discussions like these.

So one thing that I’ve heard a lot of from the folks who’ve spoken already is talking about the powers of President Washington or the First Congress. And while I consider myself to be a progressive originalist, perhaps one of the most important things that I feel is left out of the originalism discussion generally is the whole Constitution. The amended Constitution is just as much part of the Constitution as the Constitution as it stood in 1788.

We the people over time have taken advantage of the Founder’s genius in putting in the amendment process to make the Constitution over time more democratic, more inclusive, more just. And I think that is an incredibly important thing to keep in mind when we think about who we are as a nation, when we think about what our Constitution means because there were some systematic injustices at the Founding.

Fortunately, we the people remedied them through the constitutional means given to us. We got rid of chattel slavery through a constitutional amendment. We ensured that women and people who were of low economic means who couldn’t afford a poll tax were included in democracy through the amendment process. We made sure that equal citizenship was enshrined in the Constitution through the amendment process. And so to privilege the original Constitution over the whole Constitution is something that I think is a grievous error and something that happens sometimes when we talk about originalism but is something that we should all keep in mind when we’re making legal arguments, when we’re making value arguments about constitutional democracy.

I think it’s also important to remember the whole Constitution when we talk about federalism because federalism was one of the great inventions of the 18th century Constitution. But it was drastically changed by the Second Founding, as some of us call it, after the Civil War when we enacted the Fourteenth Amendment, when we gave Congress enforcement powers under the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and then subsequent rights-enhancing amendments. Obviously, we still have a federalist system, and thank goodness for that, allowing us to have state and local innovation as well as national power to provide national solutions to national problems. But that federalism was changed after the Civil War, and to not recognize that, I think, means that you aren’t actually a real so-called originalist, someone who cares about the meaning of the words of the Constitution.

But I think that everyone here is not wrong. I think that the methods and the ways that we talk about how we do originalism is an important conversation. But I think that in some ways, we have more in common than we have differences between us.

Now, I’m not going to say I’m doing originalism squared or cubed or taking the square root of it or whatever, but I think as the good judge said, if not, what’s the point? People from all sides of the ideological spectrum should be grappling with, should be arguing about the words of the Constitution. If not, what was the point? What was the point of our Founders writing it down? What was the point of these generations pouring blood, sweat, and treasure into changing the Constitution if we aren’t going to take it seriously? And I love talking about that with more conservative or libertarian audiences like this morning. I love talking about that with my fellow progressives at those gatherings. And it’s something that I think we should all agree on.

Also, because as Jack said, it fosters better politics, frankly. When the Affordable Care Act was first passed, I did a lot of debates across the country, particularly with Randy Barnett. And we would get up there and we would argue about the Committee of Detail and what they meant when they gave the Commerce Clause power and all of these things. And not only did it make for, I think, a better conversation, but also, if he got up there and talked about that, and I got up there as a progressive and said, “Who cares?”, that’s not a very good debate. I guess you’d get to dinner faster, but that’s not a very good discussion. That’s talking past each other rather than grappling with what does it mean to have a limited government? What does it mean to also want to provide for quality, affordable health care? So I think that it fosters better politics, as Jack said.

But one thing that I think is hard to get past when I talk about the idea of how all of us should come together around the text of the whole Constitution is that the label originalism does carry some baggage, especially for folks from the leftward side of the ideological spectrum, which is where I sit. Very few people these days actually practice the caricatured vision of originalism where you do a séance to try to think of what James Madison would think about applying Fourth Amendment protections to the internet. No one really does that. We talk about different ways in which you could do it, and there can be some methodological differences about how you practice originalism, but no one really does that caricatured version of originalism.

And so then we talk about, well, what was the original meaning of these words? What was the original meaning of due process? How does that change things? That’s a real debate that I think everyone should be having. And frankly, the idea that only conservatives are originalists and liberals aren’t is just wrong, and you can look at the Supreme Court to see that. You can disagree with the way that folks on one side or the other apply it, but as we’ve heard from Justices Kagan and Ginsburg, if you’re talking about looking to the text and history of the Constitution, they’re originalists too, and they’ve said that at various points.

So I think that, again, there’s more that we have in common than divides us on this particular question. Maybe on the left, I’ll have to think up a new word since originalism kind of gives everyone hives, but I haven’t come up with that slogan yet. We can talk about workshopping some of those things.

But finally, I just want to say in terms of the, “If not, what is the point?”, the words of the Constitution are also valuable to us because they give us a North Star. It took the Civil Rights Acts to bring reality to the promises of the Fourteenth Amendment. We are constantly working to live up to the words of our Constitution. And so in that sense, I think thinking about the original purpose of the Constitution is not just important as a legal matter but inspiring as an American.

[Applause]

Hon. Amul Thapar: Thank you very much. Finally, we will hear from Professor Christina Mulligan. She’s the Vice Dean for Academic and Student Affairs and Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School, and she’s going to clean all this up.

Prof. Christina Mulligan: [Laughter] Only kind of. The previous speakers have spoken about what originalism is, but these comments are going to address more what originalism is not, or at least does not have to be, not presenting a separate theory, but presenting a way of approaching the theories that we’ve just heard.

Many critics of originalism discount it or see it as illegitimate because they perceive it to be a tool for conservative white men to maintain their power over legal society. And it certainly does seem like originalists are largely conservative or libertarian or Republican, largely white, and largely male, but that’s not what originalism has to be. Originalism can be more diverse in many ways, and that diversity can be leveraged to make originalism better while sticking to the values of fixation and constraint central to originalism.

Now, talking about diversity and originalism with different audiences is a really interesting experience because different audiences are inclined to embrace and reject different parts of these claims. So with this audience, I expect the notion that originalism is a valuable method to be a relatively easy sell. You might reasonably think, “Listen, either originalism is the correct way to interpret the Constitution or not. That doesn’t change if the people who like originalism right now are conservative or white or male. If that’s how the law works, originalism is just what we’re legally obligated to do.”

But I expect the harder sell is this: that originalists can learn from the critiques of originalism that say it has problems with sex and race because those concerns get at something real and important that we can address today while still being originalist. Or maybe in other words, just because you disagree with how some people on the left talk about race and gender doesn’t mean there’s nothing to talk about.

The key insight for originalism is to recognize that some criticisms of originalism are about the past, and some criticisms of originalism are about the present. The criticisms about the past, that the Framers were white, that the Framers were male, that the Framers are dead, are things that we can argue about the relevancy of, but we can’t do anything about them. But focusing solely on the identity of the Framers misses most of the weight of the criticism of originalism surrounding sex and race. Counterintuitively, many criticisms of originalism’s relationship with sex and race are actually about what originalists do in the present.

So what are these present day criticisms? First, that originalists are homogenous in terms of their political beliefs and social experiences, and so we’re all more likely to interpret constitutional text the same way, perhaps more likely to see what we would expect, given our own beliefs and experiences, rather than what the Framers or what the amendment-ratifying era populations actually did believe. Second, that originalists focus too much on sources by the Founding era elite in contrast to other historic populations. And the third criticism, that originalists and people associated with them today, Republicans, conservatives, libertarians, just don’t really care about the rights and liberties of women and people of color. So why trust originalists if they advocate for a document that ostensibly symbolizes these racist and sexist problems?

So each of these concerns can be addressed today while being faithful to originalist methods, and I think addressing each of these concerns makes originalism better on its own terms. So for example, a less biased originalism is one in which those doing the interpretation come from a variety of perspectives. So it’s important to value having a diverse population doing originalist interpretation for its own sake. Elizabeth brings a different perspective than John, and while neither is more likely — Elizabeth and John on this panel, not like a hypothetical Elizabeth and John — and while neither of them is more likely to be right based on who they are or based on the fact that they are female or male or progressive or conservative, the fact that they look at the same evidence with a different eye increases the likelihood that they’re going to be able to see different things and correct each other’s mistakes.

A better originalism is also one that looks to a variety of historic sources. Black people and white women were present and speaking and writing throughout the Constitution’s history, most especially during the discussion and adoption of the Reconstruction amendments. They constituted the public that makes the public meaning as much as anyone else. And we can pay more attention to them. Even though many of these authors are relatively obscure, they’re there. And self-promotion alert, discussions of some of these texts appear in my article “Diverse Originalism” if you want to look it up after the panel.

Finally, and most challenging, we can start to address the alienation that many people feel from originalism and from the Constitution in a couple ways. First, we as originalists can be conscientious about applying our enthusiasm for originalism equally across legal issues. If you believe the original meaning of the Second Amendment protects a right to bear arms, make a point of emphasizing that equally, whether a gun owner in a particular case is white or black.

Second, we can be more careful to separate the morality of the Constitution from the feelings of the people who wrote parts of it. To analogize from a simpler case, whether the Declaration of Independence espouses good values does not depend on whether Thomas Jefferson was a good person. Thomas Jefferson spoke with excruciating clarity about his belief in the inferiority of black people in his Notes on the State of Virginia. Yet, the Declaration will always be a beacon that reminds us all men are created equal.

So to answer the original question of what is originalism, it’s a method by which we interpret legal meaning today through appropriate reference to yesterday. And to the extent we choose how to approach that interpretation today, we have a great deal of latitude in how well we can be originalist and how big a tent we can build.

[Applause]

Hon. Amul Thapar: Thank you very much. And for those of you that were trying to scribble fast, it’s called “Diverse Originalism,” is Christina’s article, and it’s worth reading.

So I’m going to start with the questions. Justice Scalia’s looking down on all of us and smiling because he used to say that when he was an originalist, people would go running from the room. And when we announced this panel, everyone kept streaming into the room. But as Elizabeth pointed out, some people now get hives when they hear the term originalism. So do you think originalism is a useful label and why? And after hearing all of your theories, are you all really under the same tent? And I’m going to start with Professor McGinnis and then have Professor Mulligan comment.

Prof. John McGinnis: So I think it is a useful label. Larry Solum, who’s a professor at Georgetown, says originalists are of a family of theories, and they do agree on certain things. They agree that the meaning of the Constitution was fixed, either analytically or perhaps as Steve and I do, contingently because of original methods or the law, and that’s a very important matter. The meaning of the Constitution was fixed at the time it was enacted. And secondly, we think it should at least contribute to the constitutional law today.

The difficulty, of course, is that even in families, there are black sheep. And also in families, the other difficulty is we don’t agree on who are the black sheep. And so there are a lot of divisions within originalists. And so I would just note three large matters that may, while that analytic point is absolutely true, that may divide us more in practice than unite us in theory. And so let me just lay them out very briefly because I think you should look for them. This will be discussed throughout the conference.

I think the first is how thick the meaning of the Constitution is; how much is done by interpretation and is fixed, how much is done by construction and is more open-ended. We saw a big difference between Jack and myself on that. Another question is how much should judges be aggressive in using the Constitution to invalidate the views of other branches; judicial engagement versus judicial restraint. How can that be fixed in the meaning of the Constitution? And finally, precedent. There are just thousands of Supreme Court cases, not all of them originalist. What is the theory originalists have with respect to precedent? Many of us have very different theories with respect to precedent. Some have no weight to precedent. Others give it a great deal of weight. So those practical issues, I think, actually divide originalists more than unite them, but there is a core that we all share.

Hon. Amul Thapar: Thank you. Christina?

Prof. Christina Mulligan: So I took this question from a little more of a PR perspective in does originalism as a label do the work that we want it to do? And I don't know the way out of this, but a challenge with the label originalism is that it evokes this kind of Founder worship and wanting a historical golden age to return that people more left of center might find suspicious, even though it’s not really core to what originalism is and is doing. And I get where it comes from, that it comes from rejecting a free-wheeling living constitutionalism and trying to situate it in a particular thing, place, and time. But I get a lot more mileage out of not emphasizing the original part.

So one of my colleagues before I came here says, “Why would anyone be originalist?”, like this is just some completely wild idea. And I was like, “Well, how do you interpret a statute that was passed in 1905?” And that led off into a discussion of this is just how law works, much as Steve Sachs and Will emphasize in their work a lot. And so emphasizing more this is -- we’re just doing law, this is how law works, I think makes it easier from a public relations perspective or an expansive perspective to convince people who are very nervous when they hear the word originalism because they think it means having to embrace other aspects of the 1780s. That’s not what is has to be. I don't know what other word we would use because it’s the word, but I think it’s something to keep in mind.

Hon. Amul Thapar: Thank you. So let’s answer Christina’s colleague’s question. Why should someone be an originalist? And Evan and Jack, why don’t you all tackle this? So Evan, you want to go first?

Evan Bernick: So yeah, I think that as an initial matter, just figuring out what the law is is a useful thing, regardless of whether you think the law is good or bad. Steve brought up ERISA. Simply knowing where you stand before the coercive apparatus of the state is a valuable thing, if only because to the extent that you don’t understand it, you can’t see what’s wrong with it, and you can’t change that in ways that would be more conducive to your normative convictions.

The other way, though, that originalism is valuable, at least to me, and the reason that I’m an originalist is I think that the original Constitution is pretty good. It sets up a just scheme of social cooperation. It’s worth preserving insofar as I’m interested in establishing justice, securing the blessings of liberty, providing for the common defense, and all that stuff in the preamble. Those are non-controversial, largely, political goods that the Constitution has served well in its amended form to secure over the course of at least the last several decades. And I think that’s good enough to support a commitment to the original meaning of the Constitution.

Prof. Jack Balkin: To answer that question, you need to divide it into two. First question is why does the Constitution become law? Second question is why does it continue to be law today? Answer to the first question is very easy. Constitution becomes law because of an act of popular sovereignty; actually, a series of acts of popular sovereignty, the original Constitution and then the amendment process. And then the second question is why does it continue to be law today? And that reason has already been given by several of the people on this panel; that is, it’s rule of law reasons. That is, once you make something law in our system, it continues to be law until such time as it’s lawfully changed.

Now, of course, there will be various disputes about interpretation and construction that follow on to how to apply that law. But the basic idea that the law, once enacted lawfully, continues to be the law until it’s lawfully changed is a very reasonable postulate of our system.

Hon. Amul Thapar: Elizabeth, in your comments, you talked about how maybe more people should be originalists and how you were going to try and help us host this panel at ACS, but my question is why do you think more people should be originalists? Do you believe public officials and judges should be originalist? And what about private citizens?

Elizabeth Wydra: Yeah, absolutely. And you know, we did kind of do this panel at the ACS convention, but we -- what was the title? It was “Let’s Talk about Text.”

[Laughter]

It has a little jazzier beat under it. But I think that absolutely not only should people from the left and right focus on the words of the Constitution, but I think that absolutely judges and public officials and private citizens should because, yes, the people who swear an oath to the Constitution, one would hope, would be very devoted to those words that they swore to uphold, but also, all of us live as part of the Constitution. All of us live in a country that is formed by the Constitution, and it frames our values.

And so I think that this is also where I take inspiration from the arc of progress that we’ve seen through our Constitution. I wasn’t included in democracy when the Constitution was written initially, but we expanded who is part of democracy through caring about the Constitution and changing its words. And so private citizens, I think, can take inspiration from that to see the values, the North Star in the Declaration of Independence’s great words that we are constantly struggling to make a reality for all.

And I think that public officials would do well to speak in the terms of the Constitution because they resonate with people. The average American cares about the Constitution. There’s, I think, an interesting point about you could talk to someone on the street about free speech or the Second Amendment, and they’re not lawyers, but they know what you mean. I would like people to have that resonance when we think about the rights and values of the Fourteenth Amendment, but I think it goes to illustrate just how powerful the Constitution is.

Hon. Amul Thapar: Professor Sachs, what are your thoughts on this?

Prof. Stephen Sachs: So I think the Constitution is definitely for more than just judges. And if the Constitution is for more than judges, than originalism is too. I think one of the worst things that can happen to a legal system is for it to be thought of as just the province of judges. I think a while back, there was a pamphlet that you could even get at the Supreme Court that was explaining “What is this thing?” for tourists that would say Congress makes the laws, and the Executive enforces the laws, and the Supreme Court interprets the laws.

And I think that’s actually not quite how it goes because the Supreme Court or any court interprets laws only because a case has come up that they need to decide in accordance with the law, whatever that law might be. And they have just as much and only as much province to interpret it as anyone else has who needs to find out the legal answer to a given question in a particular case. When Chief Justice Marshall was saying that it’s the province and duty of the courts to say what the law is, it’s because they have to figure it out in order to give a legally appropriate judgement. That doesn’t mean that their voice is the only voice at the table or that whatever the courts say goes. So originalism is for anyone who wants to know about our law, and that is far, far more, and has to be far, far more than just our judges and courts.

Hon. Amul Thapar: Professor Sachs, do you think originalism encourages activism or restraint? And that came up in some of your comments -- I mean, the panel’s comments. And in answering that question, can you define those terms, activism and restraint? And Professor Mulligan, be thinking about it because I’m coming to you next.