Going Rogue: The EEOC Quietly Uses FOIA To Penalize Employers For Adopting Lawful Employment Arbitration Programs

| Topics: | Labor & Employment Law |

|---|---|

| Sponsors: | Labor & Employment Law Practice Group |

Anecdotal reports from employers around the country indicate that regional offices of the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) are denying employers’ Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)[1] requests for files relating to the agency’s investigation of charges of discrimination when a resulting claim proceeds in an arbitral rather than judicial forum.

In short, under the EEOC’s current policy, an employer can receive the EEOC’s investigation file under FOIA only if the employer has declined to exercise its right to use an employment arbitration agreement with an employee. The EEOC’s position is in sharp conflict with the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) and Supreme Court precedent applying it. The FAA not only approves of employment arbitration, it manifests a “liberal federal policy favoring arbitration agreements.”[2]

It is unclear when the EEOC adopted its policy to treat employers differently under FOIA based on whether they use arbitration. What seems clear is that the agency’s position is an arbitrary administrative action without basis in, and contrary to, the governing statutes.

I. FOIA and Title VII

A. FOIA and its Exemptions

FOIA’s purpose is to allow citizens access to government information to ensure “an informed citizenry, vital to the functioning of a democratic society, needed to check against corruption and to hold the governors accountable to the governed.”[3] FOIA’s “‘basic policy’ is in favor of disclosure.”[4]

In promulgating FOIA, Congress provided nine categories of exemptions from FOIA’s disclosure provisions to protect certain governmental interests.[5] The third exemption of FOIA allows an agency to withhold records that are:

specifically exempted from disclosure by statute . . . if that statute (A)(i) requires that the matters be withheld from the public in such a manner as to leave no discretion on the issue; or (A)(ii) establishes particular criteria for withholding or refers to particular types of matters to be withheld.[6]

B. Title VII and EEOC Investigations

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (“Title VII”) proscribes discrimination in employment on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.[7] As a precondition to the commencement of a Title VII action in court, a complainant must first file a charge with the EEOC.[8]

Upon receiving a charge, the EEOC notifies the respondent and investigates the allegations.[9] If the EEOC finds “reasonable cause” to believe a charge of discrimination is true, the EEOC must “endeavor to eliminate [the] alleged unlawful employment practice by informal methods of conference, conciliation, and persuasion.”[10] If informal methods do not resolve the charge, the EEOC has the first option to “bring a civil action” against the employer in court.[11]

If the EEOC determines there is “n[o] reasonable cause to believe that the charge is true,” the EEOC is to dismiss the charge and notify the complainant of his or her right to sue in court.[12] Whether or not the EEOC acts on the charge, a complainant is entitled to a “right-to-sue” notice 180 days after the charge is filed.[13] Within 90 days following such notice, the complainant may commence a civil action against the allegedly offending employer.[14]

C. Title VII’s Non-Disclosure Provisions

Sections 706(b)[15] and 709(e)[16] of Title VII govern disclosure of information relating to the EEOC’s investigation of discrimination charges. Section 706(b) provides in relevant part:

Whenever a charge is filed by or on behalf of a person claiming to be aggrieved, or by a member of the Commission, alleging that an employer . . . has engaged in an unlawful employment practice, the Commission shall serve a notice of the charge (including the date, place and circumstances of the alleged unlawful employment practice) on such employer, . . . (hereinafter referred to as the “respondent”) within ten days, and shall make an investigation thereof. . . . Charges shall not be made public by the Commission. . . . If the Commission determines after such investigation that there is reasonable cause to believe that the charge is true, the Commission shall endeavor to eliminate any such alleged unlawful employment practice by informal methods of conference, conciliation, and persuasion. Nothing said or done during and as a part of such informal endeavors may be made public by the Commission, its officers or employees, or used as evidence in a subsequent proceeding without the written consent of the persons concerned. Any person who makes public information in violation of this subsection shall be fined not more than $1,000 or imprisoned for not more than one year, or both. . . . .

42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-5(b) (emphasis added). Section 709(e) states:

It shall be unlawful for any officer or employee of the Commission to make public in any manner whatever any information obtained by the Commission pursuant to its authority under this section prior to the institution of any proceeding under this subchapter involving such information. Any officer or employee of the Commission who shall make public in any manner whatever any information in violation of this subsection shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof, shall be fined not more than $1,000, or imprisoned not more than one year.

42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-8(e) (emphasis added).

Title VII thus expressly bars the EEOC from disclosing charges and certain related information to the “public.”

D. The EEOC’s Regulations and “Special Rules” on Disclosing Charge Files

The EEOC’s regulations addressing public disclosure state that “[n]either a charge, nor information obtained during the investigation of a charge of employment discrimination” under Title VII and other statutes for which EEOC is responsible “shall be made matters of public information by the [EEOC] prior to the institution of any proceeding under title VII [or other applicable statutes] involving such charge or information.”[17]

But the EEOC’s regulations add that “[t]his provision does not apply to such earlier disclosures to charging parties, or their attorneys, respondents or their attorneys, or witnesses where disclosure is deemed necessary for securing appropriate relief.”[18] Rather, under EEOC’s regulations, “[s]pecial disclosure rules apply to the case files for charging parties” and “entities against whom charges have been filed.”[19]

These “special disclosure rules” are found in EEOC’s Compliance Manual § 83.[20] The manual notes that “providing information to parties from their files is not ‘making public’ as meant by [Title VII §§ 706(b) and 709(e)].”[21]

Under Section 83, EEOC states that it will thus honor “requests for disclosure from charge files by aggrieved parties” where the “charging party or other aggrieved person [has] received a Notice of Right to Sue that has not expired.” EEOC Compliance Manual §§ 83.1 & 83.3(a). However, the Compliance Manuals adds that EEOC will “[d]eny requests when a Notice of Right to Sue was received and more than 90 days have passed without suit being filed.”[22]

With respect to respondent-employers, EEOC’s Compliance Manual simply directs: “Honor a respondent’s Section 83 request only if it is a named defendant in a pending private lawsuit based on the charge.”[23]

II. The EEOC’s Two Rationales for Denying Employers’

FOIA Requests for Charge Files When A Resulting Claim Proceeds in Arbitration

EEOC regional offices appear to be offering two different rationales for denying employers’ FOIA requests when a resulting discrimination claim proceeds in arbitration rather than court.

A. EEOC’s First Rationale for Denial

In recently denying one employer’s FOIA request, a regional District Office claimed that Title VII barred the EEOC from producing the charge investigation file to the employer under the circumstances. The EEOC explained:

The Commission cannot release charge file documents to the respondent unless litigation based on the charge against respondent was commenced within 90 days of issuance of a Notice of Right to Sue. Title VII States that EEOC cannot make charge information public “prior to the institution of any proceeding under this subchapter,” also explaining that within 90 days of issuance of a Notice of Right to Sue “a civil action may be brought”. See Section 709(e) and Section 706(f). Section 706(f) discusses the Commission’s authority to bring “a civil action . . . in the appropriate United States District court,” and later in the same paragraph describes an aggrieved party’s right to bring a civil action. It is the EEOC’s position, based upon the statutory text, that a “proceeding under this subchapter” refers to a civil suit based upon the charge investigated by the EEOC and filed in a court of law within the 90 days. If no such suit is filed during that period, the charging party and respondent are then considered to be members of the public for purposes of FOIA, and EEOC is therefore prohibited from disclosing to them the information in the charge files.

. . . Arbitration is not a proceeding under Title VII, as such, your client is deemed to be a member of the public. We cannot disclose the information in the charge file, therefore, your request is denied.

U.S. Equal Emp. Opportunity Comm’n, District Office, Letter of FOIA Request Denial (on file with author) (emphasis added).

But the EEOC’s reasoning here does not justify its defiance of FOIA. Nothing in Title VII says the EEOC “cannot release charge file documents to the respondent unless litigation based on the charge against respondent was commenced within 90 days of issuance of a Notice of Right to Sue.” Rather, Title VII says that EEOC cannot “make public” information obtained by EEOC “prior to the institution of any proceeding under this subchapter involving such information.” And the respondent is not the public.

The Supreme Court said as much forty years ago in EEOC v. Associated Dry Goods.[24] There, the EEOC sought to enforce a subpoena served on an employer, which refused to produce requested documents unless the EEOC agreed the documents would not be disclosed to charging parties. The EEOC refused to give this assurance, explaining its practice, pursuant to its regulations and Compliance Manual, of making limited disclosure to a charging party of information in his and other files when the charging party needs that information in connection with a potential lawsuit. The respondent-employer sued seeking a declaration that the EEOC’s policy of making such pre-litigation disclosures to parties was unlawful under Title VII.

Examining Sections 706(b) and 709(e) of Title VII along with the EEOC’s “special rules,” the Supreme Court concluded that EEOC’s policy of making disclosures to charging parties relating to charge files was lawful. The Court expressly rejected the argument that charging parties (and respondents) were the “public” to whom Title VII prohibits the disclosure of charges and related information. The Court explained:

Congress did not include charging parties within the “public” to whom disclosure of confidential information is illegal under the provisions of Title VII here at issue. Section 706(b) states that “[c]harges shall not be made public.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b). The charge, of course, cannot be concealed from the charging party. Nor can it be concealed from the respondent, since the statute also expressly requires the Commission to serve notice of the charge upon the respondent within 10 days of its filing. Thus, the “public” to whom the statute forbids disclosure of charges cannot logically include the parties to the agency proceeding.[25]

The Court further concluded that “Congress intended the same distinction when it used the word ‘public’ in § 709(e), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-8(e).”[26]

The EEOC’s first rationale for denying an employer’s FOIA request when the resulting claim proceeds in arbitration thus fails because an employer-respondent is not the “public” for purposes of Sections 706(b) and 709(e).

Moreover, even assuming for argument’s sake that Section 709(e)’s prohibition against “mak[ing] public” EEOC charge information “prior to the institution of any proceeding” applied to employer-respondents, the EEOC’s rationale for why arbitration does not qualify as a “proceeding” is also contrary to law.

The EEOC notes that Section 706(f) refers to the EEOC’s pursuing a “civil action” in a “United States district court” and to a charging party’s initiating a “civil action.” The EEOC thus states that “based upon the statutory text,” a “‘proceeding under this subchapter’ refers to a civil suit.”

But reading Title VII’s reference to a “civil action” to exclude arbitration proceedings ignores decades of Supreme Court precedent. In CompuCredit Corp. v. Greenwood, for example, the Court rejected the argument that a statute’s use of “the terms ‘action,’ ‘class action,’ and ‘court’” meant that Congress mandated that claims under that statute must proceed in an “action in court” to the exclusion of arbitration.[27] The Court explained that “[i]t is utterly commonplace for statutes that create civil causes of action to describe the details of those causes of action, including the relief available, in the context of a court suit.”[28] Accordingly, “[i]f the mere formulation of the cause of action in this standard fashion were sufficient” to exclude arbitration, “valid arbitration agreements covering federal causes of action would be rare indeed. But that is not the law.”[29] The Court cited a lengthy list of federal claims arising under statutes referring to a right to bring a “civil action” that nevertheless had been found to be arbitrable.[30] Of particular note, the Court observed regarding another employment law that requires EEOC investigation:

In Gilmer we enforced an arbitration agreement with respect to a cause of action created by the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (ADEA) which read, in part: “Any person aggrieved may bring a civil action in any court of competent jurisdiction for such legal or equitable relief as will effectuate the purposes of this chapter.” 29 U.S.C. § 626(c)(1).[31]

Thus, despite the ADEA’s express reference to bringing a “civil action in any court,” the Supreme Court held that ADEA claims may be compelled to arbitration.

Under CompuCredit, Section 709(e)’s ever broader reference to “the institution of any proceeding” cannot reasonably be read to refer only to civil actions in court but must also include arbitration.[32]

In short, the EEOC’s first rationale for denying employer-respondents’ FOIA requests for charge files when the resulting claim proceeds in arbitration relies on FOIA Exemption 3, which applies where a statute requires that matters be “withheld from the public.” The EEOC contends that Title VII prohibits the disclosure of the agency’s charge investigation file to members of the “public.” The EEOC reasons that an employer-respondent is merely a member of the “public” unless and until a matter becomes a “proceeding under Title VII” and that an arbitration is never such a proceeding. Thus, in the EEOC’s eyes, an employer-respondent that uses employment arbitration agreements with its employees is just a member of the public for purposes of Title VII’s non-disclosure provisions, even if the charging party pursues a resulting claim against the employer in arbitration.

This rationale for denying employer-respondents’ FOIA requests fails for two reasons. First, disclosure of a charge file to an employer-respondent is never disclosure to the “public” as prohibited by Section 706(b). And Section 709(e)’s reference to a “proceeding under this subchapter” does not only “refer[] to a civil suit . . . filed in a court of law” but, under Supreme Court precedent, includes arbitration. So even if disclosure of charge-related information to an employer-respondent were a disclosure to the public, such disclosure would be permitted under Section 709(e) after the claimant had initiated a proceeding in arbitration.

FOIA Exemption 3 simply does not apply in these circumstances to justify the EEOC’s denial of employer-respondents’ FOIA requests.

B. EEOC’s Second Rationale for Denial

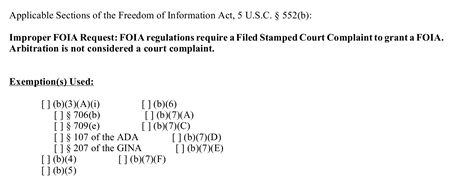

Other recent EEOC denials of FOIA requests where an employer-respondent is defending a resulting claim in arbitration have provided a different rationale. These denials do not even cite an applicable FOIA exemption but instead simply state:

U.S. Equal Emp. Opportunity Comm’n, District Office, Letter of FOIA Request Denial (on file with author).

This rationale for denying an employer-respondent’s FOIA request appears to rely on 29 C.F.R. § 1610.5, which governs “request[s] for records” submitted to the EEOC. Section 1610.5(b)(3) states in relevant part:

(b) Description of records sought. Requesters must describe the records sought in sufficient detail to enable Commission personnel to locate them with a reasonable amount of effort. . . . .

(3) A respondent must always provide a copy of the “Filed” stamped court complaint when requesting a copy of a charge file. The charging party must provide a copy of the “Filed” stamped court complaint when requesting a copy of the charge file if the Notice of Right to Sue has expired as of the date of the charging party’s request.[33]

This provision is obviously not intended to impose substantive limits on an employer-respondent’s right under FOIA to receive a copy of the EEOC’s charge file. Rather, § 1610.5(b) on its face informs employer-respondents (and other requesters) what information is to be included with records requests to assist the EEOC in identifying the records sought.

The EEOC does not point to any statutory basis for imposing a substantive requirement that an employer-respondent’s FOIA request include “a copy of the ‘Filed’ stamped court complaint when requesting a copy of a charge file.” That procedural requirement was first added to the EEOC’s regulations in 2013, and the rulemaking records do not refer to any statutory grounds for such a requirement.[34] Moreover, as a practical matter, there is no logical reason why attaching an arbitration demand in place of a court complaint would fail to serve the same purpose of “describ[ing] the records sought in sufficient detail to enable [EEOC] personnel to locate them with a reasonable amount of effort.”

The EEOC’s reliance on 29 C.F.R. § 1610.5(b)(3) to deny an employer’s FOIA request where a resulting claim is proceeding in arbitration – because it would be impossible for such an employer to attach a file-stamped court complaint – is, at best, a gross misuse of the EEOC’s “request[s] for records” regulation. At worst, it is a bad faith circumvention of FOIA and the FAA.

III. The EEOC’s Longstanding Opposition to Employment Arbitration

The EEOC’s manipulation of FOIA to penalize employers that use employment arbitration, although baseless, is not entirely surprising. The EEOC has long harbored substantial hostility to mandatory employment arbitration. In 1997, the EEOC issued its Policy Statement on Mandatory Binding Arbitration of Employment Discrimination Disputes as a Condition of Employment (“Policy Statement”), denouncing mandatory employment arbitration as “contrary to the fundamental principles” evinced in “the nation’s employment discrimination laws.”[35]

The EEOC’s Policy Statement laid out a plethora of supposed defects in employment arbitration. The Statement asserted that arbitrators and employers using arbitration lack public accountability, arbitration does not allow for development of the law, discovery in arbitration is limited, arbitration is not suitable for class actions, arbitration systems are structurally biased against discrimination plaintiffs, and mandatory arbitration adversely affects the EEOC’s ability to enforce civil rights laws.

In leveling this broadside against employment arbitration, the EEOC largely ignored the federal policies supporting arbitration that animate the FAA as well as the detailed analysis of employment arbitration set out just six years earlier by the Supreme Court in Gilmer.[36]

In that landmark decision, the Court applied the FAA to require the arbitration of a federal discrimination claim. The Court made clear there was no “inherent inconsistency” between the “important social policies” that underlay federal discrimination laws and “enforcing agreements” to arbitrate discrimination claims. The Court swatted down many of the same objections to arbitration that the EEOC would repeat in its 1997 Policy Statement. The Court explained that “[s]uch generalized attacks on arbitration res[t] on suspicion of arbitration as a method of weakening the protections afforded in the substantive law to would-be complainants,” and as such, they are “far out of step with our current strong endorsement of the federal statutes favoring this method of resolving disputes.”[37]

Because the EEOC’s 1997 Policy Statement condemning employment arbitration was already outdated on the day it was issued, the statement was largely ignored. Over the following decades, the Supreme Court and the lower courts continued to find that the FAA’s liberal federal policy favoring arbitration required enforcement of mandatory employment arbitration agreements, including with respect to the full range of federal discrimination claims.

Finally, in 2019, the EEOC relented and rescinded its 1997 Policy Statement, conceding twenty-two years after-the-fact that it “does not reflect current law.”[38]

Despite rescinding the 1997 Policy Statement, the EEOC’s deep-rooted antipathy towards employment arbitration apparently endures. While the agency has no power to ban employment arbitration, it has evidently decided it can burden employers that exercise their right under the FAA to use arbitration by nullifying their rights under FOIA.

This burden is significant. In fiscal year 2020, the EEOC received 67,448 charges of discrimination.[39] In the same year, 16,287 FOIA requests were made to the 17 EEOC offices nationwide.[40] Of those, 1,456 were denied by way of Exemption 3 of the FOIA.[41]

At the same time, according to one study, “more than half—53.9 percent—of nonunion private-sector employers now have mandatory arbitration procedures.”[42] “Among companies with 1,000 or more employees, 65.1 percent have mandatory arbitration procedures.”[43]

The EEOC’s denial of these employers’ FOIA rights in apparent retaliation for their exercising their FAA rights thus poses a significant, and almost certainly growing, problem.

[1] 5 U.S.C. § 552.

[2] Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20, 25 (1991) (quoting Moses H. Cone Memorial Hosp. v. Mercury Constr. Corp., 460 U.S. 1, 24 (1983)).

[3] N.L.R.B. v. Robbins Tire & Rubber Co., 437 U.S. 214, 242 (1978).

[4] Id. at 220.

[5] 5 U.S.C. § 552(b)(1)–(9).

[6] 5 U.S.C. § 552(b)(3).

[7] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–2(a)(1).

[8] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–5(e)(1), (f)(1).

[9] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–5(b).

[10] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–5(b).

[11] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–5(f)(1).

[12] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–5(b), f(1); 29 CFR § 1601.28.

[13] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–5(f)(1); 29 CFR § 1601.28.

[14] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–5(f)(1).

[15] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–5(b).

[16] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–8(e).

[17] 29 C.F.R. § 1601.22.

[18] Id.

[19] 29 C.F.R. § 1610.17(g).

[20] EEOC’s Section 83 disclosure provide an alternative to the procedures for disclosure under FOIA. The Compliance Manual states: “Process any request labeled ‘FOIA request’ as such unless the requester agrees that it can be handled under § 83 instead.” EEOC Compliance Manual § 83.1. EEOC explains that it is authorized to establish these special disclosure rules because “providing information to parties from their files is not ‘making public’ as meant by” Title VII §§ 706(b) and 709(e). Id. Any limitations that EEOC choses to place on the disclosures it is willing to make to parties under Section 83 should not (and could not, in any event) be read as limiting the disclosures that EEOC is required to make to parties under FOIA.

[21] Id. § 83.1.

[22] Id. § 83.3(a).

[23] Id. § 83.3(b). EEOC’s Compliance Manual policy requires that a lawsuit be filed against a respondent before EEOC will “[h]onor a Respondent’s Section 83 request.” EEOC may well be permitted by Title VII’s Sections 706(b) and 709(e) to impose this requirement for a Section 83 disclosure because those statutory provisions only state when agency disclosure is barred, not when it is required. Thus, in the absence of another requirement mandating disclosure (such as FOIA), Sections 706(b) and 709(e) leave EEOC some discretion to decide the conditions upon which it will makes disclosures under Section 83.

That calculus changes when FOIA is added to the mix. It appears that EEOC wrongly treats its narrower Section 83 procedures for making disclosures to respondents as also limiting its obligations to make disclosures to respondents under FOIA. Specifically, EEOC appears to believe that it can refuse to honor respondents’ requests under FOIA for charge files unless the respondent “is a named defendant in a pending private lawsuit.” But Sections 706(b) and 709(e) do not contain any requirement that a respondent be a “named defendant in a pending private lawsuit” in order not to be treated as the “public” for purposes of those provisions. EEOC’s attempt to use its narrower Section 83 policies to limit its FOIA disclosure obligations has no basis in Title VII. As one court has explained:

EEOC . . . argues that its long-standing policies prohibit production of the files to a party if no lawsuit was filed. While policies of an agency that are adopted in construction of a statute should generally be given some deference, I decline to do so in this instance where the policy is not supported by the statutory language at issue.

E.E.O.C. v. Albertson's, LLC, No. CIVA06CV01273WYDBNB, 2008 WL 511480, at *4 (D. Colo. Feb. 22, 2008).

[24] 449 U.S. 590, 598 (1981).

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] 565 U.S. 95, 100 (2012).

[28] Id.

[29] Id. at 100-01.

[30] Id. at 101.

[31] Id.

[32] See Raymond James Fin. Servs., Inc. v. Phillips, 126 So. 3d 186, 191 (Fla. 2013) (relying on Black’s Law Dictionary to conclude that “the term ‘proceeding’” is “a broad term and includes arbitration”). See generally Yellow Freight Sys., Inc. v. Donnelly, 484 U.S. 820, 823-824 (1990) (noting that “Title VII contains no language that expressly confines jurisdiction to federal courts or ousts state courts of their presumptive jurisdiction” and rejecting arguments that federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction over Title VII claims).

[33] 29 C.F.R. §1610.5(b)(3)..

[34] See Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 77 FR 53814-01, 2012 WL 3782971(F.R.) (Sept. 4, 2012) (explaining that Section 1610.5 “identifies the acceptable methods of submitting a FOIA request to the Commission [in person or via mail, email, Internet, or facsimile machine] including the required identification of the submission as a FOIA request and other content required for efficient processing” and that the new rule would add new subsection (3)(c) ); Final Rule, 78 FR 36645-01, 2013 WL 3009158(F.R.) (June 19, 2013). See also Final Rule 82 FR 45180-01, 2017 WL 4284059(F.R.) (Sept. 28, 2017) (further revising 29 C.F.R. § 1610.5).

[35] U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, EEOC Releases Policy Statement on Mandatory Binding Arbitration, https://www.eeoc.gov/newsroom/eeoc-releases-policy-statement-mandatory-binding-arbitration (last visited Nov. 24, 2021).

[36] 500 U.S. 20 (1991).

[37] Id. at 31-31.

[38] U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Rescission of Mandatory Binding Arbitration of Employment Discrimination Disputes as a Condition of Employment, https://www.eeoc.gov/wysk/recission-mandatory-binding-arbitration-employment-discrimination-disputes-condition (last visited Nov. 24, 2021).

[39] U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Charge Statistics (Charges Filed With the EEOC) FY 1997 Through FY 2020, https://www.eeoc.gov/statistics/charge-statistics-charges-filed-eeoc-fy-1997-through-fy-2020 (last visited Nov. 24, 2021.

[40] U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Fiscal Year 2020 Report of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on Its Administration of the Freedom of Information Act, https://www.eeoc.gov/fiscal-year-2020-report-equal-employment-opportunity-commission-its-administration-freedom (last visited Nov. 24, 2021.

[41] Id.

[42] Alexander J.S. Colvin, Econ. Pol’y Inst., The Growing Use of Mandatory Arbitration 2 (2018).

[43] Id.

Note from the Editor: The Federalist Society takes no positions on particular legal and public policy matters. Any expressions of opinion are those of the author. We welcome responses to the views presented here. To join the debate, please email us at [email protected].