Facts of the Case

David Leon Riley belonged to the Lincoln Park gang of San Diego, California. On August 2, 2009, he and others opened fire on a rival gang member driving past them. The shooters then got into Riley's Oldsmobile and drove away. On August 22, 2009, the police pulled Riley over driving a different car; he was driving on expired license registration tags. Because Riley's driver's license was suspended, police policy required that the car be impounded. Before a car is impounded, police are required to perform an inventory search to confirm that the vehicle has all its components at the time of seizure, to protect against liability claims in the future, and to discover hidden contraband. During the search, police located two guns and subsequently arrested Riley for possession of the firearms. Riley had his cell phone in his pocket when he was arrested, so a gang unit detective analyzed videos and photographs of Riley making gang signs and other gang indicia that were stored on the phone to determine whether Riley was gang affiliated. Riley was subsequently tied to the shooting on August 2 via ballistics tests, and separate charges were brought to include shooting at an occupied vehicle, attempted murder, and assault with a semi-automatic firearm.

Before trial, Riley moved to suppress the evidence regarding his gang affiliation that had been acquired through his cell phone. His motion was denied. At trial, a gang expert testified to Riley's membership in the Lincoln Park gang, the rivalry between the gangs involved, and why the shooting could have been gang-related. The jury convicted Riley on all three counts and sentenced to fifteen years to life in prison. The California Court of Appeal, Fourth District, Division 1, affirmed.

Questions

Was the evidence admitted at trial from Riley's cell phone discovered through a search that violated his Fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable searches?

Conclusions

-

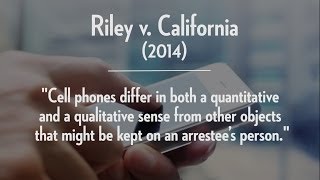

Yes. Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. wrote the opinion for the unanimous Court. The Court held that the warrantless search exception following an arrest exists for the purposes of protecting officer safety and preserving evidence, neither of which is at issue in the search of digital data. The digital data cannot be used as a weapon to harm an arresting officer, and police officers have the ability to preserve evidence while awaiting a warrant by disconnecting the phone from the network and placing the phone in a "Faraday bag." The Court characterized cell phones as minicomputers filled with massive amounts of private information, which distinguished them from the traditional items that can be seized from an arrestee's person, such as a wallet. The Court also held that information accessible via the phone but stored using "cloud computing" is not even "on the arrestee's person." Nonetheless, the Court held that some warrantless searches of cell phones might be permitted in an emergency: when the government's interests are so compelling that a search would be reasonable.

Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr. wrote an opinion concurring in part and concurring in the judgment in which he expressed doubt that the warrantless search exception following an arrest exists for the sole or primary purposes of protecting officer safety and preserving evidence. In light of the privacy interests at stake, however, he agreed that the majority's conclusion was the best solution. Justice Alito also suggested that the legislature enact laws that draw reasonable distinctions regarding when and what information within a phone can be reasonably searched following an arrest.

Learn more about the Roberts Court and the Fourth Amendment in Shifting Scales, a nonpartisan Oyez resource.

Cellphone Searches and the Fourth Amendment – Riley v. California and United States v. Wurie - Podcast

Criminal Law & Procedure Practice Group Podcast

On Tuesday, April 29, 2014 the Supreme Court held back-to-back hearings on cases testing the...

Big Win for Internet Privacy

Short video with Orin Kerr discussing Riley v. California decision

Riley v. California Post-Decision Commentary On June 25 the Supreme Court unanimously decided Riley v....

Searching Devices at the Border: What Does the Fourth Amendment Require?

In Alasaad v. Wolf, both the U.S. government and plaintiffs – 11 U.S. citizens and...

GEDMatch and the Fourth Amendment: No Warrant Required

He murdered 13 people, raped at least 50 women, and committed burglaries all across California...

Can Border Patrol Search Your Phone Without a Warrant? [POLICYbrief]

Short video featuring Matthew Feeney

The long-standing “Border Search Exception” to the Fourth Amendment allows Customs and Border Protection to...

Old Law, New Technology, and the Congressional Need To Update ECPA

Last week, witnesses before the Senate Judiciary Committee faced much more amicable questions than then-Judge...

StingRay Technology and Reasonable Expectations of Privacy in the Internet of Everything

Federalist Society Review, Volume 17, Issue 1

Note from the Editor: This article discusses cell site simulators, also known as StingRays, and...

2013-14 Supreme Court Round-Up

Summit Club (Ballroom on 30th Floor) 15 W 6th StTulsa, 74119

![Click to play: Can Border Patrol Search Your Phone Without a Warrant? [POLICYbrief]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/huBaKUs0jX4/mqdefault.jpg)