Mississippi v. Tennessee: Equitable Apportionment of an Interstate Aquifer

| Topics: | Environmental & Energy Law • Supreme Court • Environmental Law & Property Rights |

|---|---|

| Sponsors: | Environmental Law & Property Rights Practice Group |

Water is finite. Especially the usable kind. And the Middle Claiborne Aquifer holds lots of it. Unsurprisingly, both Mississippi and Tennessee want it. Luckily, instead of war, the law requires they share it. – Report of the Special Master, p. 32

In Mississippi v. Tennessee—a case of original jurisdiction and first impression—the Supreme Court held that the waters of the Middle Claiborne Aquifer (MCA) are subject to the judicial remedy of equitable apportionment, and Mississippi’s complaint was dismissed without leave to amend. The doctrine of equitable apportionment, Chief Justice Roberts writing for a unanimous Court explained, allows for the allocation of rights to a disputed interstate water resource.

For this complicated matter of environmental science and law, the Court appointed a Special Master: Judge Eugene Siler of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. The Special Master considered whether the MCA is an interstate water resource; and if so, whether equitable apportionment is the appropriate remedy. Following motions practice, discovery, and a five-day evidentiary hearing, the Special Master issued a report with recommendations on how the Court should proceed.

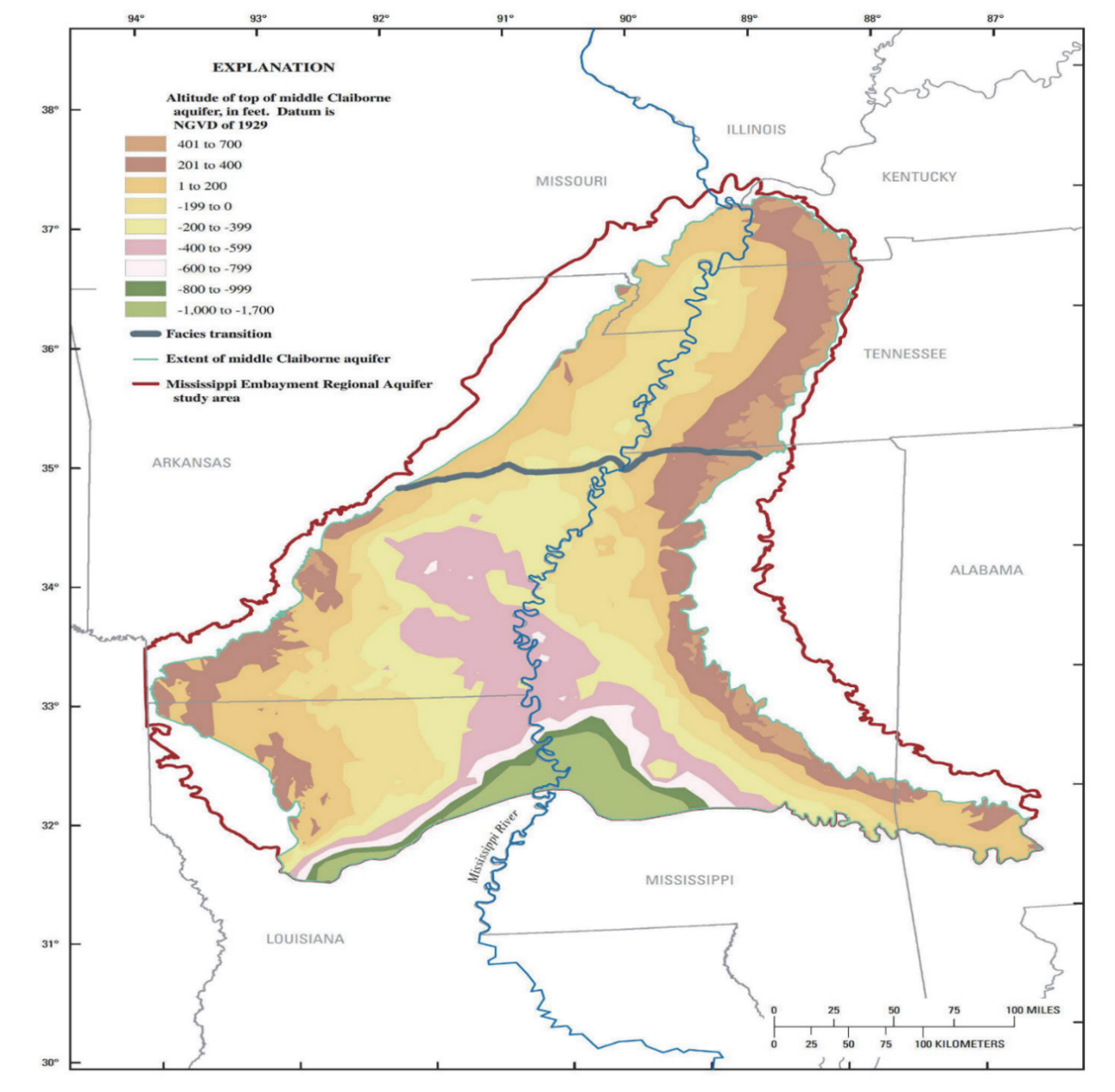

Figure 1: State boundary map with an MCA overlay. This map demonstrates the MCA’s multistate character. – Report of the Special Master, p. 16

The Special Master recommended finding that: the MCA is a single hydrological unit holding groundwater beneath eight states; equitable apportionment is the exclusive judicial remedy; and because Mississippi expressly disclaimed equitable apportionment in its complaint, the Court should grant it leave to amend. Mississippi objected to the Special Master’s recommendation that equitable apportionment applies. Tennessee, the City of Memphis, and Memphis Light, Gas & Water Division (all three defendants) subsequently cross-objected, but on the grounds that the Court should not grant Mississippi leave to amend.

The Court has considered matters of equitable apportionment before, including twice last term in Florida v. Georgia and Texas v. New Mexico. The Court typically applies the doctrine of equitable apportionment to rivers and streams, even if ephemeral. However, here, the Court was called upon to decide whether equitable apportionment applies to an interstate aquifer, a matter of first impression.

With its equitable apportionment jurisprudence, the Court intends to produce a fair allocation of shared water resources. In so doing, the Court is guided by three principles. First, whether a transboundary water resource is at issue. Second, whether the water at issue flows naturally between states. Third, whether one state’s use of the shared water resource affects the other’s use of the same. All three principles cut in favor of equitable apportionment in this case.

In its complaint, Mississippi alleged Tennessee unlawfully siphoned hundreds of billions of gallons of groundwater using roughly 160 wells located in Tennessee. Mississippi contended that in so doing, Tennessee took groundwater which would have otherwise remained beneath Mississippi for centuries. Indeed, Mississippi argued that Tennessee committed a tortious taking of its groundwater and therefore sought $615 million in damages as well as declaratory and injunctive relief.

In making its argument that the judicial remedy of equitable apportionment should not apply, Mississippi attempted to distinguish groundwater from other mediums the Court has previously considered (e.g., interstate rivers and streams). Mississippi argued that because the MCA’s groundwater has a natural transboundary flow of only one to two inches per day, it should not be subject to sharing in the same way rivers and streams are. The Court was not persuaded by this argument, for even at a mere one to two inches of natural transboundary flow per day—given the MCA’s cavernous size—the overall flow of groundwater is roughly ten billion gallons per year. Thus, the Court found the MCA’s relatively slow speed of flow did not place it beyond equitable apportionment.

Mississippi also tried to analogize the instant action to Tarrant Regional Water District v. Herrmann, a case in which the Court found one state may not physically enter another to take water in the absence of an express agreement. Again, the Court was unpersuaded by Mississippi’s argument because Tarrant concerned the interpretation of an interstate water compact, and no such compact was at issue here.

Generally, Tennessee countered Mississippi’s arguments by stating that its pumping, filtering, and piping of the disputed groundwater took place on wells located entirely within its sovereign boundaries. The Court did not reach the merits of Tennessee’s argument, but it did state in dicta that Tennessee’s pumping of MGA groundwater contributed to a “cone of depression” extending miles into northern Mississippi. If Mississippi were to pursue further action on this matter, it could attempt to tie the Court’s reasoning on this point into a finding that any such cone of depression reduced Mississippi’s groundwater storage and pressure.

At bottom, the Court found equitable apportionment of the MCA would be sufficiently similar to past applications of the doctrine concerning rivers and streams and therefore that it should apply. It did not award Mississippi tort damages. As such, the Court overruled Mississippi’s objections, sustained Tennessee’s, and dismissed Mississippi’s complaint without determining whether it should be granted leave to amend.

The Chief Justice went on to explain that if Mississippi were to seek leave to amend, then its complaint would be subject to the Court’s longstanding rule that a state seeking equitable apportionment must prove by clear and convincing evidence some real and sustained injury or damage. For Mississippi, satisfying this heightened standard could be a difficult task.

Note from the Editor: The Federalist Society takes no positions on particular legal and public policy matters. Any expressions of opinion are those of the author. We welcome responses to the views presented here. To join the debate, please email us at [email protected].