Confirming that no good deed goes unpunished, a Brooklyn federal court just awarded $6.7 million to a collective of 21 graffiti artists who for years were allowed to spray paint an abandoned Queens warehouse. The owner of the 5Pointz building didn’t seem to mind that the artists were regularly painting and repainting the walls of the warehouse, though everyone involved knew the owner eventually was going to tear it down and build apartments. The problem, however, was that the graffiti art could be protected under the federal Visual Rights Arts Act because it had obtained some culturally significant status in the world of spray-can art.

And once the aerosol artistry attained this status, it transformed itself from graffiti to a protectable property interest belonging not to the owner of the canvas (i.e. the building) but to the artists.

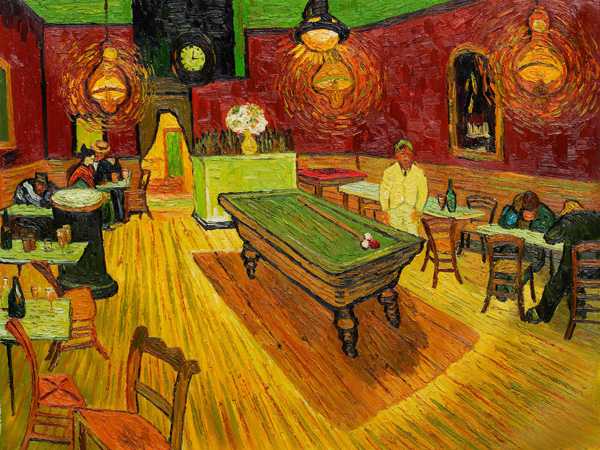

From a property rights perspective, this case is fascinating because the federal government has essentially created a new property right in artistic works that started out as trespasses against the property interests of the real estate owner. When the owner announced his intention to tear down the building, the artists tried to buy it – but they couldn’t afford the $200 million price tag. In the art world apparently $200 million can buy you either a graffiti-covered warehouse or a stolen Night Café by Van Gogh. Lacking a spare $200 million, the artists promptly sought an injunction to stop the demolition. When the artists failed to get an injunction, the building owner immediately whitewashed the entire collected works of the pop-art Picassos in the dead of night. That act of self-preservation eventually led to this week’s $6.7 million verdict.

It’s one thing to create a new private property right out of something new – like an apple crop in an orchard or a patent. And the government can create new private property from government property – like a homestead grant. But to create new private property out of other people’s private property is troubling. Unlike cases of adverse possession where the owners have essentially abandoned their rights, the owner here always intended to redevelop the property and told the artists about his intentions.

Indeed, when the government has done this in other contexts, the government has been forced to walk back its taking or pay for it. Thus, if the government takes your property for a highway, it has to pay you for it. And in Kaiser-Aetna v. United States, the Supreme Court rejected an attempt by the Army Corps of Engineers to allow trespassing boaters onto private property. And there are 4th Amendment concerns as well. When the City of Charlottesville published a map encouraging hikers to walk on private property, the 4th Circuit found in Presley v. City of Charlottesville that the City had violated the 4th Amendment. More recently, the Supreme Court mused that there could be such a thing as a “judicial taking.” Here the federal government has carved out a $6.7 million interest in property out of the hide of another property owner. If I were the owner of the one-time whitewashed warehouse Watteau, I’d seriously think about suing those responsible for this $6.7 million bill.