Volume 14: Issue 2

The Financial Crisis and the Free Market Cure: A Conversation with John A. Allison

Note from the Editor:

Note from the Editor:

The following is a transcript of a Federalist Society Practice Group Teleforum Conference Call that took place on Thursday January 10, 2013 featuring John A. Allison, President & CEO of the Cato Institute. The audio recording of this call is available at: http://www.fed-soc.org/multimedia/detail/the-financial-crisis-and-the-free-market-cure-podcast. This transcript is mostly unedited.

As always, the Federalist Society takes no position on particular legal or public policy initiatives. Any expressions of opinion are those of the speakers. The Federalist Society seeks to further discussion about the issues involved.

Additionally, John A. Allison; Henry T.C. Hu, University of Texas School of Law; Jonathan R. Macey, Yale Law School; and Jide Okechuku Nzelibe, Northwestern University School of Law, participated in a related panel on “Crony Capitalism” at the Federalist Society’s Annual Student Symposium in March 2013. The panel is available here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ynurTedhcV4

Guest Speaker:

John A. Allison IV, President and CEO,

Cato Institute

Moderators:

Wayne Abernathy, Chairman,

Financial Services Executive Committee, The Federalist Society

Dean A. Reuter, Vice President and

Director of Practice Groups, The Federalist Society

ANNOUNCEMENT: Welcome to The Federalist Society’s Practice Group podcast. The following podcast hosted by The Federalist Society’s Financial Services and E-Commerce Practice Group was recorded on Thursday, January 10, 2013, during a live telephone conference call held exclusively for Federalist Society members.

DEAN A. REUTER: Welcome to The Federalist Society’s Practice Group Teleforum Conference Call featuring Mr. John Allison. I am Dean Reuter, Vice President and Director of Practice Groups at The Federalist Society.

All expressions of opinion are those of the experts on today’s call. Also, please note that this call is being recorded for use as a podcast in the future.

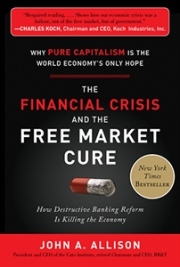

Today, Mr. John Allison will speak about his new book, The Financial Crisis and the Free Market Cure. A link to the book was provided to you in a notice of this call and is also available on The Federalist Society’s website.

Our call today, we are going to mix things up a little bit. It’s going to take the form of an interview to be conducted by the Chairman of The Federalist Society’s Financial Services Executive Committee, Mr. Wayne Abernathy. The interview portion of the call is going to last for about the first half of the call, the first 30 minutes or so, and after that, we are going to get to the questions from you, the audience.

So, with that, Wayne, please go right ahead with your questions for Mr. Allison.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: Great. Thank you very much, Dean, and many thanks to all of you on the call and especially our thanks to John Allison for taking this time out of, I’m sure, an always busy day to participate in this call with us.

Let me give you a very brief introduction of our distinguished guest today. John Allison is the longest-serving CEO of a top 25 financial institution, having served as Chairman of BB&T for 20 years. He currently serves as President and CEO of the Cato Institute and is a former distinguished professor at the Wake Forest University Schools of Business. He is also one of the lead spokesmen for banking and policy reform today, appearing at universities and business groups nationwide. He received a lifetime achievement award from American Banker and was named one of the decade’s top 100 most successful CEOs by Harvard Business Review. We could go on extensively, but what I’d really like to do is get to John and get an opportunity for him to talk a little bit about not only his book, but a lot of the thoughts and ideas that went behind it and additional observations that he has in connection with what we see unfolding in the financial and policy world today.

John, I’ve read your book. I will note that the full title of the book is The Financial Crisis and the Free Market Cure: How Destructive Banking Reform is Killing the Economy. That’s the full title. I found the book insightful, informative, well worth reading, and stimulated a lot of questions, but the first question I’d like to put to you, if I may, is, as you know and as I think many of us do who have been following these issues, a lot of books and thousands of pages of newspaper and magazine articles have been written about the financial crisis, what caused it, how it developed, what its lessons are. Why did you feel that you needed to write a book about it?

JOHN A. ALLISON: Well, thank you, Wayne, and thanks for that introduction.

I guess, basically, Wayne, I thought it would be interesting to have a book written by somebody that actually knew what happened.

All these commentators and academics have no idea what happened. I was the longest-serving CEO of a major financial institution in the United States, so I got to see the book from the inside. And related to that, I think that the statists have done a wonderful job in creating a very destructive myth, and the myth is that the financial crisis was caused by deregulation of the banking industry and that what we need is a highly regulated environment along with “greed on Wall Street.” The banking industry wasn’t deregulated, and of course, we’ve had greed on Wall Street in my 40-year career, and it wasn’t like a greed plague that swept out of the north that caused the financial crisis.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: Let’s dig in then to some of the substance of that, because I think that’s one of the things that I noted, not only reading your book, but in reading some of the others, the various other books that are out, and I was thinking, “What does this person really know about what he’s writing about?” I got into your book, and I’m thinking, “Well, here I’m going to look at the point of view from somebody”—I mean, you were—not only were you involved with the unfolding of the crisis itself, but unfolding of the steps that led up to it, and I think that’s what’s really interesting in what you have to say.

I want to jump to the concluding chapter, not that I read it that way. I went from the beginning, and I was very disciplined and went all the way through, but in the concluding chapter of your book, you make what some would say is a very bold statement. And I’m going to quote now, and this is a quote, “Government policies are the primary cause of the recent great recession and the related slow economic recovery,” end quote. Now, that would seem to trump the public narrative that was all about greed on Wall Street, as you mentioned, and the failure of complex investment strategies and so forth. I think while few would deny that there’s a government involvement and even culpability, you’re assigning top billing to government policies. How do you figure that?

JOHN A. ALLISON: Well, that’s a great question, Wayne. Basically, you have to begin with the concept that we don’t live in a free market in the United States. We live in a mixed economy, which varies a lot by industry. Technology is largely deregulated and has done very well. Financial services is the most regulated industry, and it’s done very poorly. It’s kind of an oxymoron to argue that the most regulated industry caused these problems and therefore that was market failure. It’s kind of a crazy idea. The three primary culprits that caused the financial crisis were: errors made by the Federal Reserve, errors by the FDIC, and then finally government housing policy.

We don’t have a private monetary system in the United States. In 1913, when the Federal Reserve was created, the government nationalized the monetary system. They owned the monetary system just like the government owns highways—if the interstate highway bridges were falling down, people would say, “Well, hey, the government owns the highways. It’s their fault. They own these bridges.” Well, the Federal Reserve owns the monetary system in the United States. They make all the rules. The Federal Reserve was created in theory to reduce volatility in the economy, but in practice, what they do is reduce volatility in the short term and create bigger problems in the long term.

In a free market, businesses are being created, and businesses are being destroyed. The destruction process is, interestingly enough, as productive as the creation process, because it frees up resources that are being used poorly and allows them to be used better. When you stop the downside of the process, all you do is push problems into the future, and that’s exactly what the Fed has done.

And then specifically, leading to this crisis, in the early 2000s, Alan Greenspan, who was the long-term head of the Fed and wanted to be a hero, because he was getting ready to retire, printed too much money, i.e., he kept interest rates way low, that incentive excess leverage, and that excess leverage is what really led to the financial crisis.

It got helped. Well, the Fed got help from the FDIC, because the FDIC insurance destroys market discipline, and what happens in that case—and resources will go to the people that use FDIC insurance to buy, use FDIC insurance, pay the highest interest rate from deposits because people don’t worry about how risky their deposits are because the government is guaranteeing them, and those are the people that finance the high-risk lending activities—people like Countrywide.

And then the bubble ended up in the housing market because of government housing policy that really goes back 50 years, but went exponential based on the decision made by Bill Clinton in 1999 to require Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, these giant government-sponsored enterprises, to have at least half their loan portfolio in what’s called affordable housing, i.e., subprime lending. And Freddie and Fannie were so big, they dominated the housing market. When they failed, they owed $5 trillion, and they had $2 trillion in subprime mortgages. And they also had such a large market share, private competitors—now, some of them did make mistakes, and I’ll talk about that in a minute, but how did you compete against somebody this big that was lowering the lending standards trying to reach this arbitrarily imposed guideline by the government, and it sucked the home market down. Freddie and Fannie would never exist in the free market. They only existed because their debt was guaranteed by the U.S. government, and they were leveraged 1,000:1. That means it would be like having a net worth of $10,000 and owing $10 million, and you can only do that if the government guarantees it.

In a fundamental sense, the Federal Reserve printed too much money trying to avoid a natural market correction that was happening in the early 2000s. That created a bubble. The bubble got pushed into the housing market because of these affordable housing policies that sounded good, and it was executed through Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. The bubble burst, destroying trillions of dollars of wealth and millions of jobs.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: Now, in saying that, you’re not trying to say that there were no mistakes made by the industry in this process, are you?

JOHN A. ALLISON: No. No. A lot of banks made large mistakes, and I would have allowed those banks to fail. In fact, it’s frustrating to me that Citigroup has been saved three times in my career, and every time, they get bigger and worse. And I believe as long as the government continues to bail what I call “crony capitalist institutions” out, like Citigroup, they will get bigger and worse, because if you have an implicit government guarantee, then you are going to take a lot of risk in the good times.

So, yes, a large number of financial institutions made really serious mistakes, should have been allowed to fail, their resources being reallocated, but those mistakes would not have caused the financial crisis without the government policy, without the errors made by the Federal Reserve, FDIC insurance that allowed those mistakes to take place in smaller institutions, and this huge push of government policy encouraging people to make high-risk home loans.

I mean, it’s ironic that people like Dodd and Frank, who wrote the reform legislation 2 years before this happened, were putting enormous pressure on the whole industry to do subprime lending, i.e., affordable housing lending.

So, yes, individual institutions did bad things. Countrywide did some really crazy stuff—should have been allowed to fail— but it was always in the context of government policy, and it never could have been a systemic problem without the Federal Reserve and Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: Let me ask a question about the bailouts and government assistance and so forth. Maybe if I can be permitted to make an historical allusion, Frederick the Great is reportedly mocked, having mocked the delicacy of the Austrian Empress, Maria Theresa, over the 18th century dismemberment of Poland, and these are the words he said, “She weeps, but she takes her share.”

Aren’t you vulnerable to a similar criticism? You roundly fault the TARP investment in banks in your book, and yet BB&T under your leadership joined in and received Treasury TARP money. Not all banks did, but BB&T did. How do you respond to that criticism?

JOHN A. ALLISON: That’s a great question, Wayne, and a lot of people have asked me that, that issue.

When TARP was announced, when they were getting ready to try to get it done in the legislation, I was the only CEO of a large financial institution that was adamantly opposed to TARP. I actually lobbied Congress. I thought that they were fixing the wrong problem, and I still—and I’ll draw a circle around this at the end of this section here.

But anyway, even though I was opposed to TARP, it passed anyway, obviously, and then when TARP passed, we did take the money. And here’s what happened, and this tells—I think this is important for attorneys to understand. It tells you about the lack of rule of law we have in the United States today. When TARP passed, the day afterwards, I got a call from our regulator, because I was a known opponent to TARP, the only large bank that was vocally opposed to TARP, and I got a very interesting message. This is a regulator of the FDIC. He says, “Listen, you know, John, BB&T has way more capital than you need by traditional capital standards; however, we decided we need new capital standards. We don’t know what those new capital standards are going to be; however, we’re confident that you don’t have enough capital under these new standards unless you take the TARP money. And we’ve got an audit team ready to come in tomorrow, and we’re pretty confident you will fail this audit unless you take the TARP money,” and we said, “We’ll take the TARP money.”

Now, here’s the question. Why would government policy people want us to take the TARP money? All right, [Ben] Bernanke, who is the head of the Federal Reserve, he is a student, he is an academic. He knows very little, frankly, about commercial banking. He’s an academic, and he wrote a paper about the Great Depression in which Roosevelt tried to save individual banks, and it didn’t work. The market jumped on him when the government tried to help him. The three large banks getting ready to fail, Bernanke believes that if he tries to save these individual institutions, it won’t work. So he needs to force the large banks. He doesn’t care about the small bank. That’s why the small banks who did—all large banks participated. A lot of small banks didn’t, and all he cares about is $100 billion and over banks, and he’s particularly concerned that the healthy banks participate, because if the healthy banks don’t participate, it’s going to be obvious what he’s doing. And this happened to some other large, healthy banks. He puts intense pressure on the large healthy institutions to participate.

The other factor, and I think this is interesting, now, [Hank] Paulson who is running the Treasury is an investment banker. Now, if you’re an investment banker, and you know you’re going to be judged after the fact about how good your investment is and you have the power of the government, you have a gun, effectively, who do you want to participate in this program? The people you know can pay you back, right?

So you radically improve the odds of TARP looking good after the fact by forcing banks that don’t need the money to take this money, and it was an enormously high interest rate. There were penalties in terms of warrants they took on our stock. It cost BB&T between 50- and $100 million for money we absolutely did not need, we never used, and then when they came back afterwards and they did something called the “stress test,” they said, “Well, you didn’t really need this capital, after all.” So it was a very interesting experience, but it tells you a lot about the rule of law, which there isn’t any.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: Well, tell me if you think I’m wrong with this, but it seems to me that Dodd-Frank has increased the leverage of the government to force banks to do what they might not want to do.

JOHN A. ALLISON: Oh, absolutely. It’s really scary because Dodd-Frank instead of—you can argue about the bankruptcy laws, but Dodd-Frank is basically giving the regulators the right to make up the total rules after the fact and decide the distribution of assets and creditors. It’s a really scary assignment of power to regulators. I don’t see how the market can even figure out what’s going to happen under the Dodd-Frank rules.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: Well, in that connection, you’ve said in your book and also on the call today that the banking industry is perhaps the most heavily regulated industry in America, maybe in the world. Some assert that this regulation is necessary to protect everyone else’s freedom, that if we don’t have a strong public oversight of how banks do their business, that bankers through their control of private and public finances would exert undue influence over everything that everyone does. While anyone may criticize this or that particular regulation, isn’t the overall heavy regulation necessary on the banking industry to protect all the rest of us from what bankers can do to us?

JOHN A. ALLISON: You know, that’s a very interesting question. From 1870 to 1913, there was no central bank in the United States. There was nothing like the FDIC, obviously. We had a totally private banking system, and those private banks operated based on trust and confidence in the market, and they operated, they had to operate, were forced to operate with the gold standard, because nobody would—if they couldn’t convert their species to gold, nobody would have done business with them.

During that period of time, we did have some economic corrections. They were all short. They were very severe, but they were very short, and we had the greatest economic growth in the history of man. There are huge economic incentives, of course, for banks to try to allocate resources rationally, because that’s the optimal return to their shareholders. They don’t bank as free private entities, would never do something like get involved in the irrational distribution that affordable housing, i.e., subprime lending, did because those []would have never been good investments in the free market. Individual institutions make mistakes, but they don’t tend to make the same mistake.

Under regulatory policy, what happens is you actually radically increase the system’s risk because you force people into the same kind of wrong decisions if they turn out to be wrong. For example, the way government policy, government regulations had us allocate capital in the business, you had to have one-half as much capital for a subprime loan as you did for a loan to Exxon. So, of course, resources went into subprime home lending. So regulations actually increase the risk.

Now, here’s the issue: The real risk in the banking industry is the Federal Reserve. It’s when the Federal Reserve makes errors, like it probably is doing today, when it prints money willy-nilly, leads people to make poor investments, typically leads people to over-consume, and that’s what housing was. It was overconsumption. You consume a house just like you consume an automobile, and so the Federal Reserve, trying to keep us from having the rational economic cycles and the rational economic corrections, encourages overconsumption, and that creates the risk in the industry. So it’s kind of a Catch 22, because we don’t have a private banking business based on a gold standard that the government can’t fool with. And we have this government-created “they can print money any way they want to.” That creates the risk in the system, which then periodically banks do systematically fail, which then justifies more regulation.

So if you’re going to have FDIC insurance and the taxpayers are going to guarantee people’s liabilities, then, of course, you’re going to have regulations to go with it, but it never ends. The regulatory cycle—banks get blamed for public policy errors, which justifies more and more irrational regulations, until eventually you have the really serious problems in your financial system, which we’ll have in 10 or 15 years if we continue where we are.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: So I think in part, what I’m hearing you say is that if a heavy-handed regulation is justified in terms of making sure that banks don’t have undue influence on the rest of the economy, in practice, it’s allowed government officials working through the banking system to have undue influence on what the rest of us do.

JOHN A. ALLISON: Exactly. It destroys the rational allocation of capital. It really does.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: We’re talking, again, here with John Allison, who is currently the President and CEO of the Cato Institute and very recently was CEO of BB&T, one of the largest banks in the United States, and talking about his book, The Financial Crisis and the Free Market Cure.

I’d like to ask you, John, if I could, more of a forward-looking question, if I may. You argue about the Federal Reserve policy and how it fed the housing mortgage bubble, and that Federal Reserve policies during and since the recession are feeding the next bubble. Do you see signs of that bubble forming now, and if so, where should we look?

JOHN A. ALLISON: You know, it’s very hard to see bubbles in advance, because you tend to get rationalizations around them. They usually are always seen after the fact, but clearly, we are experimenting with Fed policy in something that’s never been done in history. We’ve been running a global experiment that probably in the long term—and I’m not predicting immediately—it doesn’t end well, because since 1971, the reserve currency of the world, the U.S. dollar, has not been tied to a commodity that’s not manipulatable by politicians, i.e., there’s no gold standard. For 5,000 years, the reserve currency always could be tied back to a commodity, traditionally gold, that was not manipulatable—at least it was harder to manipulate it than just printing money like the Federal Reserve can.

So what we’ve got going on today, the global currency war, for lack of a word, it’s almost like a trade war. As the Fed debases the U.S. dollar and the Europeans debase the euro, the Japanese are now debasing the yen, the Swiss are debasing their currency, it’s kind of a race to debasement, and the history is not good, because if you just print money without improving productivity, you lead people to make bad economic decisions, misinvestments. The misinvestments today, certainly one area you could look at would be agricultural land values that make no economic sense based on likely commodity prices. There may be a misinvestment in the stock market. It’s hard to know.

But here’s what’s ironic, and here’s what may create more of a Japanese-looking phenomenon than the traditional inflation phenomena. On one side, the Federal Reserve is printing money like crazy, but what’s happening is banks are raising reserves like crazy. They aren’t lending the money out. They aren’t lending the money out because there’s no loan demand for two reasons. One, the typical successful businessperson is very cautious today, because he’s looking at our government running huge debts and saying, “What does that mean?” He’s cautious because he knows the Fed prints money, and he doesn’t know what that means for prices. So the people that should and could borrow money are scared to. At the other end of the spectrum, the Federal Reserve regulators—the other end of the Federal Reserve—has tightened lending standards radically, so we don’t make these, quote, “bad loans” again. They’re the tightest lending standards in my 40-year career.

And they just issued some new lending standards for consumers. I haven’t seen the actual standards, but I guarantee you, they are going to be very tight standards. The regulators have pushed a lot of people out of the credit market. The credit is not available to them. So, on the one hand, the Fed is printing this money; on the other hand, it didn’t get used because the Fed itself has tightened the lending standards. And that can create more of a Japanese-style, really slow, low-growth rate without inflation, but a very destructive kind of economic environment in terms of real growth and improvement in standard of living. And I don’t think we’ve ever had the Fed make the combination of directional moves of this magnitude: print money so fast and tighten lending standards at the same time so fast.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: No, we’re on new ground. That’s for sure.

Let me ask a question now about the banking industry itself. Some people say that the biggest banks in the United States are too big and that they should be broken up. Do you agree, and if so, what is the optimal size for a bank in the United States?

JOHN A. ALLISON: Wayne, I don’t think anybody knows that question, because we don’t have a private market. There is no way that you can academically determine the optimal size of a bank, because only markets can determine that. In much of the rest of the world, the industry is actually more consolidated than in the U.S., but they have highly regulated banking markets too.

In addition, one of the ironies is that it’s very clear that the long-term policy of “too big to fail,” which has really gone back at least to the ‘80s, if not before, maybe much before that, has caused consolidation in the industry. As I mentioned earlier, Citigroup wouldn’t be here. We wouldn’t be worrying about this. They would have been broken up by the market long, long ago.

In addition, the incentive for institutions to stay large is very powerful when you have an implicit government guarantee. Go back to Citigroup. Citigroup has been trading for less than book value for years. Now, in a rational market, if you’re trading for less than book value, the signal to investors is break up your company, because you could be liquidated, but why don’t they do that? Well, who wants to give up a government guarantee? Now, there may be ego issues and other things, but who wants to give up a government guarantee? So this implicit government guarantee is causing banks to be bigger than the natural market.

I think we’ve got a horns of a dilemma, and here’s the horns of the dilemma. It is that there’s no way that government bureaucrats know how big banks ought to be. There’s no way to answer that. On the other hand, if “too big to fail” is being used as an excuse for Dodd-Frank and really very statist regulation of the whole industry, then I’d make a deal if I were in charge. Let’s set a cap on bank size, and I’ll just pick up a number, $750 billion, and simultaneously, let’s get rid of all 95 percent of bank regulation, because the justification is we’re protecting the taxpayers. Let’s force banks to have more capital, and then if they get in trouble, they just get to fail. And the market would really buy that if you really would let go of the regulatory side and the implicit guarantee. If you just broke them up and you kept Dodd-Frank and all this other stuff, then that’s very irrational, but it would be better to break them up for a tradeoff for the serious and material deregulation of the industry, so at least the rest of the banking industry could operate as private entities and allocate capital properly.

You know, if you want to control an economy, control how capital is allocated. This Dodd-Frank is the biggest statist move certainly since the Great Depression, since the New Deal, because basically government bureaucrats, through this consumer agency, can decide not only what kind of loans a bank can’t make, but they can also make you make certain types of loans, and therefore, they can allocate capital for noneconomic reasons. And that’s exactly what caused the mess we’re in, the subprime lending, affordable housing mess. What happens, of course, it’s worse than socialism in this sense. The regulators, the government bureaucrats, can make this happen, and then if it doesn’t work, they blame the banks, right? They don’t take responsibility for what they caused to happen. In a socialist environment, if they own the industry and it fails, at least they get some kind of blame for that. This is a very destructive form of statism.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: And all of the pieces of this nasty mix all fit together.

JOHN A. ALLISON: They really do. They really do.

Some people that wanted to move towards statism took advantage of the myth that deregulation caused the financial crisis, and by the way, that is a myth. Banks were not deregulated. There was a massive increase in regulation under George Bush. We had the Patriot Act, the Privacy Act, [and then later] Dodd-Frank. Banks were not deregulated. We were misregulated.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: You didn’t feel like you were being deregulated during those last couple of decades?

JOHN A. ALLISON: Absolutely not. It was unbelievable. They were threatening to put us in jail over the Patriot Act and over the Privacy Act, and so that was not deregulation. It was misregulation.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: Well, I want to ask you one more philosophical question, and then we’ll open up the questions to questions from the callers. So I will say, Dean, in a minute, we’ll turn the time over to you, and you can tell people how to call in with their questions, and if any of you listening have questions you want to ask, please get ready to do that.

So here’s a question I’ll put to you, John, and then we’ll go to the floor. A philosophical question, you called for the separation of business and state, as profound a rule of separation as we have between church and state. Would you elaborate on what you mean by that?

JOHN A. ALLISON: That’s a really important issue. You have to start with what you really view the proper role of government is, and the Founding Fathers of the United States’, I believe, view [was]—and I happen to agree with them—that the role of government was fundamentally to protect individual rights. Government really exists to protect the rights of individuals, and that means that government has a very important role, because it really has to prevent the use of force and fraud—which is a kind of force—a mental kind of force, but often more destructive than physical force, and that government is really in that business of preventing the use of force, fraud, preventing the use of physical force.

Now, that means government has got some pretty powerful and important obligations, and then it shouldn’t be doing anything else, because it’s only in the business of protecting individual rights. And the reason the Founding Fathers wanted that constraint is the government has a gun—and people with guns can do very destructive things. So there’s an important role for national defense to defend this from the bad guys. There’s a really important role for police to defend us from domestic bad guys, and then there’s a really important role for court systems, and we need a very effective and thoughtful legal process around courts.

But governments aren’t in the business of redistributing wealth. They aren’t in the business of controlling monetary policy. None of those things are what governments were designed to do. And even things in the U.S. government, they were talking about minting coins, but that didn’t mean they had no idea or would have dreamed of something like the role the Federal Reserve plays today. So I think it’s really important that you begin with the idea that the role of government is to protect individual rights. The Federal Reserve holding interest rates below what the market is a massive redistribution of wealth from savers to people that borrow money. Most of these savers are old people—we see it in the banking business. They’re largely older ladies who worked hard and saved, and now when they’re holding rates below and they can’t live on their interest income, that kind of redistribution of wealth is not a legitimate function of government.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: Hard to reward your cronies if there’s an ironclad rule against mixing the state and business, isn’t it?

JOHN A. ALLISON: Exactly. And what’s happening, of course, crony capitalism is what people think of as capitalism today, and that’s why there’s such an anti-business move, and they’re right. Unfortunately, our society is not—we don’t have a capitalist society. We have a crony capitalist [society]. I use the word “crony statist,” because it’s an oxymoron. Capitalism, that the government can’t redistribute wealth, and what it does, now it’s redistributing wealth to whoever has the most political—you saw that in this new tax bill. It was amazing how many crony capitalist provisions were included in this tax bill, and that’s really bad, and it’s unhealthy for our economy.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: We’re talking with John Allison, who is currently the President and CEO of the Cato Institute and recently, just recently retired from being CEO of BB&T, served for some 20 years as Chairman of BB&T and CEO. We’re now willing to pause the conversation where I put some questions to John, and I think, John, you’re ready and willing to take some questions from our callers.

JOHN A. ALLISON: Absolutely.

QUESTIONER: You identified all sorts of problems, and short of relying on our Second Amendment right to change government, what realistically can be done to start to fix the problem that we have with overregulation?

JOHN A. ALLISON: That’s a great question. I wish I had the absolute answer to that. I think it’s on a number of fronts.

The Institute I’m with now, Cato, we’re a libertarian organization, and our role is really to defend the concept of limited government, and it’s about liberty, individual rights, free markets. And we’re fighting on a number of fronts. What we try to do is philosophically defend basically what I believe were the ideas of the Founding Fathers of the United States: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. And we also try to do that by concretizing it in a way that people can understand the negative consequences of other behaviors, negative consequences of huge, massive deficits, the negative consequences of government spending more than 50 percent of the GDP of the United States. And what many people that, I would say, are of statist mindset, at least superficially, have good intentions, or they think they have good intentions, and what we are trying to do is convince that group that what they think is good in fact is bad. There historically have been a few success stories.

The welfare reform that happened under Bill Clinton, it happened not because conservatives have been opposed to welfare forever, but because a lot of the liberals—both opinion leaders[and] liberal thinkers— started seeing research that showed how destructive welfare had been for low-income families and low-income individuals, and they were open for welfare reform. The reform wasn’t as good as it ought to be, and it’s drifted back and all that kind of stuff, but basically because there was overwhelming evidence that the welfare reform wasn’t achieving the goal that they intended.

So what we do at Cato—and there’s lots of ways to approach this problem, but what we try to do is influence what we call “elitist communicators.” That’s people in academia, but it’s also people in the media, and we try to do it across the whole political spectrum because we think it’s important to talk to the choir, but you have to talk to other people too. Because the choir, the people that believe in liberty, unfortunately, I believe are a minority today, and we’ve got to convince a lot of other people that either hadn’t thought about these issues or their tendency is in the wrong direction.

And where we’re talking to people that philosophically agree with us, we reinforce the philosophical principles, and then we talk about the practical conclusions with very objective, analytical, mathematical research. When we start talking to people that are of statist nature, we try to present the facts in a manner that undermines their arguments, not necessarily believing that we can get them to agree with us, but we can at least get them to change their opinions and their positions or change the strength of their opinions and their positions.

And for me personally, this goes back to the first question that Wayne asked me. I wrote this book a lot to debunk these myths that deregulation caused the financial crisis and greed on Wall Street caused the financial crisis, because if statists can hold that myth, then there’s a whole set of conclusions that you come to—in government policy that you come to. If you realize that’s a myth, that it’s not true, that in fact government policies caused this financial crisis, you get a very different set of conclusions.

So we work with students. There’s lots of ways to have this fight, but where we’re focused and where I’m personally energized is trying to impact elite communicators across the political spectrum with objective refuting of statist ideas, because they are destructive.

QUESTIONER: I just want to ask you a quick question, and I think I know the answer to this, but I would love to get you to say this out loud. When you talk about errors in housing policy creating—or helping create the financial crisis , including pressure on banks to support affordable housing, implicitly you’re talking about Community Reinvestment Act, aren’t you?

JOHN A. ALLISON: Yes, yes. Community Reinvestment Act: this is where you have to be careful about this, because a lot of the statists will come back and will say, “Well, the numbers in the Community Reinvestment Act were not that big.” Well, mathematically, they weren’t huge, but they set an ethical context that really was the foundation for the whole mess. In other words, banks were not designed to do low-income lending. Banks are lending other people’s money, for goodness sake, and so we weren’t supposed to be high-risk lenders.

The Community Reinvestment Act put huge regulatory pressure on banks to get into a business that they shouldn’t have been in, in the first place, and then you couldn’t do mergers and acquisitions. But also, at some point, you were bad. You were morally out if you weren’t doing enough community reinvestment, i.e., making enough high-risk loans that you really shouldn’t have been making in the first place, and that really was kind of the beginning of the mess on Wall Street, created by two things. One was obviously there were economic incentives in lower income rate, but there was also ethical incentives. This was something you were supposed to be doing. Now, you combine something you’re supposed to be doing with something you can make a lot of money to do and you get a really interesting and very destructive incentive system, and that was what was going on here.

So, yes, the Community Reinvestment Act was really a big step in this process, and particularly for setting the foundation that banks should be in this business and that it was the right thing to do, and that was the foundation for a lot of the bad decisions.

QUESTIONER: I’m wondering if you would look into your crystal ball and tell us what you see happening in the next few years if the status quo is not changed, if the current trajectory doesn’t get altered.

JOHN A. ALLISON: I wish I had the absolute answer to that. I’m going to tell you what my most likely scenario is:

If you look at economic history, the single biggest driver of economic growth rates is how big government is in the economic system. Obviously, as I just talked earlier, there is a role, an important role for government, but once government gets over about 10 percent of the economy, it always becomes destructive, and the higher percentage it gets, the more destructive it is. And once you go over 35 or 40 percent, it becomes exponentially destructive. That’s exactly what’s happening in Europe.

If you look at federal spending, state spending, municipal spending, and particularly if you add in the cost of regulation, the total cost of government is way over 50 percent of the GDP of the United States. We’re in line with Greece and lots of those other places.

Now, what usually happens, unfortunately, in a way, is while you have these short-term fears of crises, you don’t usually get a crises until an extended period of time, and here’s what typically happens in history, and it’s happened to lots of countries throughout history. Our natural real growth rate is probably 3 percent, real growth rate. We will probably get a 1 to 2, more likely 1.5 kind of real growth rate going forward with this much government spending. What that means is we’re way suboptimizing what our economy ought to be doing, so that our real standard of living for lots of people will actually be falling in that kind of economy, and it’s kind of a slow death until you finally get a point where you create a social dysfunction and you get riots. And typically, then unfortunately, you move usually towards more statism. You get a Venezuela or an Argentina.

So if we don’t change direction, my own prognosis is we will still have some kind of economic recovery, but we will be stuck in low gear, stuck as a way higher than appropriate unemployment rate, even worse than that, in a way, stuck at a way underemployment rate—in other words, there’s people that aren’t even looking for jobs because they have given up, and now they’re on some form of welfare, food stamps, or whatever, and so you have an underproductive economy, which the compound difference between 1.5 and 3 percent over 15 and 20 years is huge, and it usually leads to some kind of really negative social consequences and an increase in government.

So we need to change the underlying policies, and how you finance government matters some, whether you pay taxes, whether you have deficits and debt related to that or whether you have inflation, but the big factor—and Milton Friedman knew this —but it’s not what he got the Nobel Prize for—we need to identify government spending. So fighting government spending is the single biggest thing we could do to keep this kind of economic slow death from happening to us.

I do worry a little bit about people—I mean, it’s possible we’re going to have some kind of economic upset because Europe falls apart or something, but people crying “wolf” too much is going to undermine our arguments. We have got to have a more sophisticated argument that really points out sometimes you have these short-term crises, but more likely, the crises are 10 or 20, 15 years down the road, but once we get so close to it, we won’t be able to fix it. We really need to move soon or the mathematics go against us because the demographics of the baby-boomers, and the real problem is the government spending related to Social Security and Medicare goes exponential in about 6 years. And if you don’t fix it now, wow, is it going to be hard to do.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: John, that economic malaise, you know, it’s one thing if we’re talking about a Greece or a second-level country in terms of size. What does it mean for the leader of the free world?

JOHN A. ALLISON: I think it’s a global disaster. The United States has an odd situation. We have the world’s reserve currency; therefore, we can do what Bernanke is doing and what the federal government is doing. We can print money and—I mean, I don’t know if your audience would understand this, but last year, almost half of the government debt was bought by the Federal Reserve. That is a bizarre phenomenon, and it could only happen—Greece couldn’t do that, because they don’t have the world’s reserve currency.

Now, the good news is we’re able to do that, and good news in a very short-term superficial sense. The bad news, it means that we’re the emperor with no clothes, and when the rest of the world wakes up, which will inevitably happen if we don’t change direction, I would say, within 5, 6 years, we will have an unbelievable economic disaster, because we will have leveraged ourself off the chart with the level of debt we have.

So we have this strange temptation, which is helpful in the short term and incredibly destructive in the long term. One of the reasons that I am a huge advocate of forcing the Federal Reserve onto a monetary scene, which I’m sure would be gold, is because the discipline it implies. I do not believe that Congress, Republicans or Democrats, will actually control deficits. As long as the Federal Reserve can print money and buy the debt, I think we will go broke. Countries usually go broke by hyper-inflating, and you get to be Zimbabwe down the road. That’s what will happen unless the Federal Reserve is disciplined, and I think that’s why something like a gold standard is so important, because I don’t think it just disciplines the Federal Reserve—I think it disciplines Congress, because as long as Congress can print money through the Federal Reserve and buy back U.S. debt, we will keep leveraging until somebody says, “Hey, the emperor has no clothes.”

QUESTIONER: John, appreciate what you’ve said. I have this question for you. We understand that government policy has done a great deal to cause the most recent crisis. There’s also a lot of people who believe that private interests have a great deal to do with the formation of government policy, and you’ve indicated some ways that the policies that have been put in place have benefitted certain interests. And if you study Dodd-Frank, I think you would agree that these problems are getting worse in recent years, not better. The policies are getting even worse.

Do you think that business leaders are—as they advocate certain policies, some of these policies, are they showing less self-restraint? Are they advocating more aggressively in their private interest over time, over the 40 years that you’ve been observing? And if that’s true, how does it affect your strategy for improving the situation?

JOHN A. ALLISON: Well, that’s a great and, I think, very important question. I think, unfortunately, in my career, we’ve had a radical drift towards more crony capitalism, and again, I think the proper term is “crony statism,” and we’ve got what is a vicious reinforcement cycle. And I saw this in the banking business. The bigger the role the government plays in the economy, both the more temping and more necessary it becomes to focus on government relationships. In other words, if you aren’t part of the process, you get punished because you aren’t in the process. Not only do you not get a favor, you get a punishment, and clearly, the bigger government gets the more important role it plays, the more that both temptation, and one can argue the necessity, for businesses being involved in government, and that is very destructive.

I’ll give you some of kind of how that happens. For years and years, Microsoft had no government[relations]—they did no lobbying, and then their competitors, other businesses, went to the Justice Department—the government—and gave a bunch of information and encouraged the government to enter into an antitrust suit against Microsoft. Now Microsoft, out of self-defense initially, has a huge army, spends hundreds of millions of dollars on government relations, and now they often go to the Justice Department—or periodically go to the Justice Department and try to get them, the Justice Department, to act against some of the same competitors. So you create this vicious incentive system for business to be involved in government.

One of the things that I thought was really tragic in my industry: if you look at a lot of people that were selected, and I won’t name names, to replace some of the CEOs who went through the financial crisis, they were primarily selected because of their ability to deal with government regulators, and that is a terrible criterion . But the ability—boards are aware of that in a highly regulated industry like banking, and particularly in large institutions, it’s very—and even board selection now is driven to some degree by “these people will be acceptable to the regulators.” And I think that is a really bad trend.

In terms of how you to fight it, I think you have to fight it in principle and not defend business— defend free markets, and I think sometimes—and I don’t want to pick on—sometimes political parties, and let’s say specifically the Republican Party, defends crony capitalism things instead of defending free markets, and those are very differences in kind, and that’s when you get the pushback where the average Joe was saying, well, “Why in the world would they say to a very large financial institution to let my local builder go broke?” And that’s a fair question. And the answer is that the large financial institution had political clout, disguised the system’s risk, and the local builder didn’t, or why did they save the unions in General Motors? Because they had political clout, not because—and, you know, General Motors went through a bankruptcy. That’s this whole conversation. All that happened in the General Motors bankruptcy—they protected the union pension plans at the expense of all the other bondholders. That’s all that bankruptcy was about, because General Motors could have done a regular bankruptcy. And so you have to say “wow.” This goes back to the question. You’ve got to separate the government from economics, from business, and that’s the principle, because it always leads to these distortions.

I think, unfortunately—it’s going to be almost impossible to convince the CEOs of large public companies, because they’ve got such a vested stake in their relationship with the government. A lot of entrepreneurs, though, are really hurt by this process, and so small businesses are hurt by this process. The people that you might, get energized on this issue are the victims —because crony capitalism usually hurts somebody too. It’s not always consumers. It’s often other businesses, and helping other businesses that are actually victims of crony capitalism understand that they are being hurt can at least get some of the business community on the side of limited government.

QUESTIONER: I work in the accounting industry, and I would like to ask you to comment on the growth of compliance and the dedication of dollars and resources to pure compliance, with any kind of regulation, versus investment in core businesses. And I would also, as an addendum to that, comment that I’ve heard more Fortune 1000 CEOs say they just want certainty rather than take a stand against this increasingly invasive responsibility environment, except for people like Frank Sullivan of RPM International here in Northeast Ohio, who is alone among, I think, many of his Fortune 1000 brethren, but if you could comment on compliance,[and] if you could comment on again further what people can do to sort of educate those—if not the CEOs now, those who are up-and-coming middle managers, even accounting and business graduates about the efficacies of the free market, how to do this in an environment where professors have again a vested interested in not a free market.

JOHN A. ALLISON: Wow! That’s a very integrating and important question.

First, in terms of Fortune—particularly—I want to say Fortune 500 CEOs, most of them today, unfortunately, have a reason they don’t get excited: they’re unhappy about regulations, but while they would just as soon have certainty, regulations tend to benefit large firms, relatively, even if they have high regulatory cost.

When I started with BB&T, we were a really small bank, and we grew it into a large institution, tenth largest in the U.S., and even though regulation drove me nuts and it’s much worse today, the burden was still less for BB&T than it is for a community bank, because in a community bank, the CEO can’t hire other people to do that, and community banks have very limited real smart human beings. And if their energy is focused on regulation instead of production, it’s a killer for that small business.

Large businesses, [even] if they don’t like [regulation]— the reason they like certainty at some level, what regulation tends to do is stabilize the status quo and hurt the innovators and creators. So that’s why—so it’s almost protective in some ways of large businesses.

Second question, regulatory burden has gone up exponentially in my career and particularly, frankly, since the Obama administration, but, I mean, it was bad under Bush. But we’ve had a regulatory explosion, and you can’t even measure it by the increase in regulations.

As I was commenting earlier, we don’t have rule of law in the United States. We have rule of regulators, and what the regulators do, Congress passes some sound-good law and leaves huge discretion to the regulators to interpret it. They interpret it, intentionally, very broadly. So, in good times, they don’t put much pressure on this regulation, and then in bad times they tighten the regulatory standards, mostly driven by whoever is the president, who is actually, ultimately the boss of the regulatory structure. So if they know that the president believes in a lot of regulations, without changing a single regulation, the regulatory standards change radically. So it has been a—I know in my company, we’ve hired thousands of people to be involved in some kind of compliance program, but that hadn’t actually increased employment, because we couldn’t afford to do it, because they weren’t producing any revenue. They were just producing cost. So, effectively, what we’ve done is reduce our productive workforce. We’ve reduced investment and innovation. The banking industry, financial industry has practically had no innovation since Dodd-Frank was introduced. Partly, it was the uncertainty, but secondly, it’s the huge cost in risk and innovation.

So the price is less focus on production, less focus on innovation, less investment, and real productive systems. Most of our technology investment is some kind of regulatory design system. We are making technological investments to make regulators happy, but those investments don’t produce real wealth and well-being long term.

In terms of convincing people, I mentioned earlier what Cato does. When I was at Wake Forest—between the time I was with BB&T, I did teach in the graduate business school at Wake Forest—I put my focus on younger people. I find that once people get over a certain age, it’s difficult to convince them about a concrete policy. It’s very hard to convince them philosophically, and if you don’t have a philosophical foundation, then you have to take one policy at a time, which is a long, long struggle. But if we can get younger people to have the right ideas, we improve the probability of success.

The main obstacle we have that you described is the vast majority of professors in American universities today are statists, and there are many people that are devout socialists and communists that teach your students. I mean, it’s amazing how dominated the academy is by—and I don’t mean just liberal. I mean left wing people whose ideas are anti—they’re anti-American, and they’re certainly anti-free enterprise, but the one piece of good news is a lot of that stuff does come across as dogma, and a lot of smart kids, they kind of see that they’re not really being presented with the truth. They’re presented with kind of this dogmatic world view, and particularly the better and brighter ones [see that].

So I think it’s very important to introduce the ideas to them. I’m a big advocate of books. Personally, Atlas Shrugged was a book that changed my world view, and I find that when students read Atlas Shrugged, many of them have an “aha.” Friedrich Hayek wrote a very powerful book called The Road to Serfdom. That is another, what I call, conversion book. So there’s a book called—it’s a simple book, called Economics in One Lesson, which is not so philosophical, as it shows the issue of unintended consequences of sound, good policies and major economic fallacies. So the most powerful thing I have found with students is to try to get them to read some of the books of liberty, and Atlas Shrugged happens to be number one on my list, but The Road to Serfdom, Economics in One Lesson—there’s a series of books available that I think are really important in that regard.

WAYNE ABERNATHY: Well, I’d like to end with one sentence from almost the last sentence of your book. You say—and it gives me hope. You say, “The advocates of a free society based on individual rights and limited government have the moral high ground.” I always believed that if you got the high ground, you can win, so appreciate those comments. Appreciate you taking the time with us today, John.

JOHN A. ALLISON: Absolutely.

DEAN A. REUTER: Well, this is Dean Reuter again on behalf of The Federalist Society. I want to thank Wayne Abernathy, of course, and also John Allison very, very much for joining us today. We certainly appreciate your insightful comments, and to our audience, I invite you to join us for our teleforum conference call Tuesday at, I believe, 3 p.m. when we will be from the courthouse steps talking about a Supreme Court case being argued on Tuesday, but until then, we are adjourned. Thank you very much, everyone.

Thank you for listening. We hope you enjoyed this Practice Group podcast. For materials related to this podcast and other Federalist Society multimedia, please visit the Federalist Society’s website at www.fed-soc.org.