United States v. Pheasant: A Rare Bird That Might Be a Good Vehicle to Revive the Nondelegation Doctrine

| Topics: | Administrative Law & Regulation • Federal Courts • Federalism & Separation of Powers |

|---|---|

| Sponsors: | Free Speech & Election Law Practice Group |

Respected jurists and scholars alike have lamented that the Constitution’s prohibition against Congress transferring its legislative power—including its power to write federal crimes—to unelected bureaucrats seems to be as dead as the Dodo. But that prohibition may yet rise like a phoenix to revitalize the health of our constitutional republic in a case that has largely flown under the radar: United States v. Pheasant. U.S. District Court Judge Robert Jones in Nevada dismissed a criminal indictment after finding that a provision of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) unconstitutionally delegated Congress’s legislative power to write crimes to a federal agency, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The government has appealed this ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

Pheasant involves an Icarus-like criminal prosecution of a dirt biker stemming from an alleged taillight infraction on federal land managed by the BLM. The incident occurred in the context of “a special operation” by BLM “to ensure a ‘family-oriented recreational experience’ at Moon Rocks,” Nevada. Mr. Pheasant and his companions were allegedly rooster tailing their dirt bikes at night without their tail lights on when a BLM officer gave chase, his feathers ruffled. Things went downhill from there, leading to Mr. Pheasant’s prosecution.

Here’s the snare: Congress has not passed legislation setting standards for dirt biker taillights, let alone chosen to criminalize the alleged infraction at issue here. Who, then, decided that failure to use a taillight at night while riding a dirt bike in a remote desert area should be a crime? The answer: unelected bureaucrats at BLM by administrative edict. How did this happen?

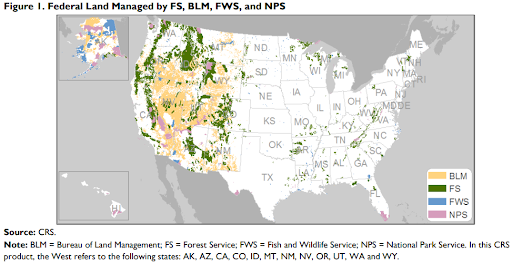

By way of background, the BLM is a federal land management agency that exercises law enforcement powers. The agency has “a massive reach” and “is today the nation’s largest land manager,” “manag[ing] 245 million acres of public lands . . . and 700 million acres of mineral estate.” This means the BLM manages 10 percent of the country’s land and 30 percent of its mineral resources. In Nevada, where these events took place, BLM manages 63% of the state’s land mass. A picture is worth a thousand words.

That is what 245 million acres of land looks like. Essentially, Congress has tasked an administrative body with managing an area of land that is almost as large as Texas and California combined.

In so doing, Congress has also purported to empower BLM to act as legislature and governor over this wide swath of land, effectively wielding the powers of a sovereign within the borders of its kingdom. A provision of the FLPMA grants BLM standardless, unchecked power to write crimes. Under the statute, to write a crime all the Secretary of Interior must do is find a regulation is “necessary.” There is no requirement for preliminary factfinding, nor any meaningful limiting criteria bounding the Secretary’s discretion and power. On top of this, BLM regulations purport to grant state BLM Directors discretion to issue supplementary rules that are binding within their jurisdictions “as he/she deems [them] necessary.” As Judge Jones observed: “In a state like Nevada, these State BLM Directors are essentially single-person legislators and governors because they promulgate regulations (laws) and enforce the regulations (laws).”

In short, Congress essentially empowered the BLM with the crime-writing powers of a state legislature and a state governor, outsourcing its nondelegable duty under the Constitution to “make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States” to unelected administrators. This delegation lets the agency “promulgate a plethora of rules from housing policies, to traffic laws, to firearms regulations, to mining rules, to agriculture certifications,” thereby granting it “unfettered legislative authority to promulgate rules for over 48 million acres of land [in Nevada.]” (Nevada is not unique in this regard. “Almost half the State of Utah, about 23 million acres, is federal land administered by” BLM.) For example, BLM has used its legislative authority to criminalize uncertified hay, mulch, or straw possession, camping longer than authorized, use of nonconforming seatbelts, and picking up rocks in certain areas. As Judge Jones observed, BLM has used its crime-writing power “to write regulations criminalizing behavior that the state would normally criminalize, like outdated vehicle registration, coal exploration, horse adoption, noisiness, fraud, discrimination, and homelessness.” And, as relevant here, BLM has criminalized failure to use a taillight at night on federal land.

BLM is not the only agency with such powers. Today, most federal criminal law is created by unelected bureaucrats issuing regulations. To put this in perspective, “[i]n contrast to the roughly 200 to 400 laws passed by Congress, the federal administrative agencies adopt approximately 3,000 to 5,000 final rules each year.” There are untold thousands of regulations governing private conduct in the 180,000 pages of the Code of Federal Regulations.

Why are unelected bureaucrats allowed to write federal crimes? After all, our Constitution exclusively tasks the people’s elected representatives with making policy choices, subject to constitutional limits on federal power. And under the Constitution, the political branches may only do so through duly enacted legislation that survives bicameralism and presentment, a deliberately difficult process designed to ensure such laws reflect broad political consensus.

This was by design. The Constitution’s separation of powers ensures that the American people know exactly who to hold accountable at the ballot box for failed or unpopular policy choices. More importantly, this system of checks and balances protects individual liberty. As James Madison famously warned in Federalist 47: “The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands . . . may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.” The power of government is at its zenith when it can jail or even execute citizens. Forty percent of the Bill of Rights is concerned with how government may go about prosecuting and punishing criminal acts. Of all powers then, the power to create crimes and punish citizens for criminal acts must be left to the peoples’ representatives in Congress.

One might think then that in this country Congress alone has the power to write federal crimes. As Chief Justice Marshall wrote, “the power of punishment is vested in the legislative,” which means “[i]t is the legislature . . . which is to define a crime, and ordain its punishment.” The Supreme Court has held that “[o]nly the people’s elected representatives in Congress have the power to write new federal criminal laws.” And as now-Justice Gorsuch has observed, “[i]f the separation of powers means anything, it must mean that the prosecutor isn’t allowed to define the crimes he gets to enforce.” Unsurprisingly, “[f]or many jurists, the question of Congress’s delegating legislative power to the Executive in the context of criminal statutes raises serious constitutional concerns.” For good reason: These delegations “mak[e]” the agency “the expositor, executor, and interpreter of criminal laws.” Yet the Supreme Court’s current precedent largely blesses this arrangement, allowing Congress to transfer its crime-writing power to unelected administrators so long as an “intelligible principle” exists to guide the agency.

Why is Judge Jones’s dismissal of the indictment in Pheasant important? To borrow a phrase from Lawrence of Arabia, big things have small beginnings. And Judge Jones’s ruling that the provision of FLPMA granting BLM unfettered power to issue any “regulations necessary to implement the provisions of th[e] Act with respect to the management, use, and protection of the public lands” backed by criminal penalties violates the nondelegation doctrine is the legal equivalent of a Golden Pheasant (apparently, the tenth-rarest bird in the world).

Respected federal judges have justifiably lamented that the “non-delegation doctrine has become a punchline” “more honored in the breach than in the observance.” And as Justice Alito has observed, “since 1935, the [Supreme] Court has uniformly rejected nondelegation arguments and has upheld provisions that authorized agencies to adopt important rules pursuant to extraordinarily capacious standards.” But even under the Court’s modern light-touch nondelegation test, there are at least theoretical limits on Congress’s ability to transfer its crime-writing power to federal agencies. And the Supreme Court has hinted at times, without definitively determining, that the test should be stricter in the criminal context. Indeed, the only two cases in which the Court found a nondelegation violation, Panama Ref. Co. v. Ryan and A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, involved standardless delegation of crime-writing powers.

Against this backdrop, Judge Jones held that FLPMA’s transfer of Congress’s crime-writing powers crossed the constitutional line. He found the statute’s “language provides the Secretary of the Interior with unfettered legislative authority.” Judge Jones continued: “Beyond the Secretary of the Interior’s ability to legislate for whatever they see necessary is the power to write regulations criminalizing behavior.” Judge Jones zeroed in on the constitutional problem: “The statute does nothing to cabin the Secretary of the Interior’s ability to choose what is a crime. With no limiting language, the statute gives the Secretary of the Interior the authority to promulgate its own criminal code on 68% of the land in Nevada, giving the BLM a larger jurisdictional area than the state police.” Put another way, “the BLM controls a majority of the land in Nevada and has the authority to write the laws on that area of public land, acting with as much authority as both the state legislature and the governor.” For Judge Jones, this was a bridge too far. The facts did not help the government’s cause, as Judge Jones previously warned the government at the status conference: “[I]n light of the current trend of the Supreme Court, you sure don’t want to die on this sword, especially when you don’t have a gun pointed at an agent, you just have a rooster trail of rocks. . . . This is not a very good case to die on the sword.” He wrote that “[t]he Court understands the gravity of this Order.” Yet he nonetheless concluded that “[w]ithout an intelligible principle, the statute is unconstitutional and the regulations promulgated thereunder that Pheasant allegedly violated are dismissed.”

That is a big deal. And if Judge Jones’s ruling is ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court, it could go a long toward improving the health of our constitutional Republic by restoring to the legislative branch the responsibility for lawmaking—especially the creation of federal crimes. In short, this is a case to watch.

It is also worth acknowledging and crediting the work of the federal defenders representing Mr. Pheasant in this case. It is particularly noteworthy that this case is not the product of nonprofit strategic litigation, but the work of a federal public defender zealously advocating for his client. As Judge Jones observed at the status conference, Mr. Pheasant’s counsel submitted a “[v]ery well-written brief on over delegation of legislative authority to the agency for the criminal counts.”

After he received the citation from the BLM officer, Mr. Pheasant “walked over to his vehicle, revved his engine, showed his taillight, put his fist in the air, and rode away yelling.” It paints an almost revolutionary picture reminiscent of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s song “Free Bird.” And perhaps an ideal case to demonstrate why our founders placed the power to create new federal crimes in the hands not of the magistrates who enforce them but of the peoples’ representatives in Congress.

Note from the Editor: The Federalist Society takes no positions on particular legal and public policy matters. Any expressions of opinion are those of the author. We welcome responses to the views presented here. To join the debate, please email us at [email protected].