Volume 14: Issue 2

EPA’s Retrospective Review of Regulations: Will It Reduce Manufacturing Burdens?

Introduction

Introduction

|

Through a series of Executive Orders, President Obama has encouraged federal regulatory agencies to review existing regulations “that may be outmoded, ineffective, insufficient, or excessively burdensome, and to modify, streamline, expand, or repeal them in accordance with what has been learned.” This paper examines the initial results of that review to understand whether actions pursued under this initiative are likely to be successful at reducing regulatory burden. Since reports suggest that the manufacturing sector bears greater regulatory burdens than other sectors,1 and that regulations issued by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) impose particularly high costs on this sector,2 the focus here is on the expected effects on the manufacturing sector of EPA’s identified reforms. |

The paper first reviews the President’s directives to agencies, and EPA’s retrospective review action plan. It then examines the effect of EPA regulations on the manufacturing sector through several different lenses. Finally, it evaluates the regulatory actions EPA identified through its retrospective analysis to determine whether they can be expected to reduce regulatory burdens on the manufacturing sector.

I. President Obama’s Initiatives

Building on the efforts of previous presidents, President Obama issued three Executive Orders (EOs) during his first term that direct agencies to conduct retrospective analysis of existing regulations.

On January 18, 2011, President Obama signed Executive Order 13563, Improving Regulation and Regulatory Review, which reaffirmed the regulatory principles and structures outlined in President Clinton’s Executive Order 12866. In addition to the regulatory philosophy laid out in EO 12866, EO 13563 instructs agencies to

consider how best to promote retrospective analysis of rules that may be outmoded, ineffective, insufficient, or excessively burdensome, and to modify, streamline, expand, or repeal them in accordance with what has been learned. Such retrospective analyses, including supporting data, should be released online whenever possible.

EO 13563 additionally instructs executive branch agencies to develop and submit to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) retrospective review plans “under which the agency will periodically review its existing significant regulations to determine whether any such regulations should be modified, streamlined, expanded, or repealed so as to make the agency’s regulatory program more effective or less burdensome in achieving the regulatory objectives.”

On July 14, 2011, President Obama took another step toward retrospective review when he issued Executive Order 13579, encouraging independent regulatory agencies to develop and make public plans for retrospective review of their regulations.3

Following these two Executive Orders, OIRA Administrator Cass Sunstein issued guidance to the heads of executive branch agencies and independent regulatory commissions with instructions for the implementation of the Executive Order’s requirements:

Executive Order 13563 recognizes the importance of maintaining a consistent culture of retrospective review and analysis throughout the executive branch. Before a rule has been tested, it is difficult to be certain of its consequences, including its costs and benefits.

The guidance instructs agencies to use the principles established in EO 13563 §1–5 to orient their thinking during the process of retrospective analysis and specifies elements their review plans should include, and timelines for sharing them with the public. Both President Obama’s Executive Order and Sunstein’s guidance on its implementation call for agencies to identify rules that are “excessively burdensome” when evaluating the effects of existing rules.4

On May 10, 2012, President Obama issued Executive Order 13610, Identifying and Reducing Regulatory Burdens, “in order to modernize our regulatory system and to reduce unjustified regulatory burdens and costs.” The Executive Order makes clear that regulations play an important role in the protection of public health, safety, and welfare, but also that they have the potential to impose “significant burdens and costs” on the public. The EO emphasizes the importance of public participation in the retrospective review process, sets a schedule for agencies’ retrospective review status reports, and sets the President’s priorities for the identification of rules for review:

In implementing and improving their retrospective review plans, and in considering retrospective review suggestions from the public, agencies shall give priority, consistent with law, to those initiatives that will produce significant quantifiable monetary savings or significant quantifiable reductions in paperwork burdens while protecting public health, welfare, safety, and our environment. To the extent practicable and permitted by law, agencies shall also give special consideration to initiatives that would reduce unjustified regulatory burdens or simplify or harmonize regulatory requirements imposed on small businesses.

As did EO 13563 and the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) implementation guidance, EO 13610 emphasizes the reduction of regulatory burdens.

Reviews of existing regulations have already been undertaken in past administrations, with mixed results.5 What will separate the Obama administration’s review of existing rules from previous efforts will be the ability of major regulatory agencies, such as the EPA, to successfully use retrospective review as a tool to reduce the burden on the regulated public.

II. EPA Retrospective Review Plan

One month following the issuance of EO 13563, EPA solicited public input through dockets and listening sessions on the design of its preliminary retrospective review plan, which the agency published in May 2011. Following publication, EPA solicited public comment on the preliminary plan and released the final plan three months later. Since the plan has been finalized, EPA has published four progress reports tracking implementation of these actions.

In its August 2011 final retrospective review plan, EPA outlined the regulatory actions underway or pending that conformed to the requirements of EO 13563 and OMB’s implementation guidance for agencies. The Agency summarized its goals for a 21st century approach to environmental protection early in the retrospective review plan, with an emphasis on an outcome of burden reductions:

During our 40-year history, EPA and our federal, state, local, tribal, and community partners have made enormous progress in protecting the Nation’s health and environment through EPA’s regulatory and stewardship programs. However, just as today’s economy is vastly different from that of 40 years before, EPA’s regulatory program is evolving to recognize the progress that has already been made in environmental protection and to incorporate new technologies and approaches that allow us to accomplish our mission more efficiently and effectively. A central goal, consistent with Executive Order 13563, is to identify methods for reducing unjustified burdens and costs. (emphasis added).

The plan outlined 35 regulatory actions that would reduce paperwork burdens, streamline existing rules, and update regulatory requirements to reduce regulatory overlap. Ultimately, EPA anticipates $1.5 billion in savings over the next five years as a result of ongoing retrospective review, or about $300 million annually. Electronic reporting, improved transparency, innovative compliance approaches, and systems approaches and integrated problem-solving comprise the core of EPA’s approach to reducing burdens through regulatory review. The following sections address manufacturers’ regulatory burdens, with an emphasis on EPA regulatory burdens, and what effect EPA’s retrospective review actions will have on burdens borne by the regulated public and manufacturers.

III. Regulatory Burden: Manufacturing

Research from sources both within6 and outside7 the government suggests that manufacturers bear a heavy burden from the existing regulatory framework. During the George W. Bush administration, reform of regulations applicable to the domestic manufacturing sector was a component of OMB’s multi-year effort to modernize or rescind outmoded rules. In its 2004 report to Congress on the costs and benefits of regulation, OIRA observed that “the cumulative costs of regulation on the manufacturing sector are large compared to other sectors of the economy.”

In response to this large burden, OMB requested public nominations of promising regulatory reforms relevant to this sector. In particular, commenters were asked to suggest specific reforms to rules, guidance documents, or paperwork requirements that would improve manufacturing regulation by reducing unnecessary costs, increasing effectiveness, enhancing competitiveness, reducing uncertainty, and increasing flexibility.8

OMB received 189 distinct nominations for reform in response to this solicitation, illustrating the need for reforms to reduce regulatory burdens on the manufacturing community. According to a 2005 OMB report, a majority of these suggested reforms “address programs administered by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Labor, a pattern that reflects the large impact of environmental and labor regulation on this sector of the economy.”9 Of the 76 reform nominations that were accepted by agencies, exactly half were related to EPA rules, and about 15 percent were related to DOL rules.

A. MAPI Report

A recent report commissioned by the Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation (MAPI), Macroeconomic Impacts of Federal Regulation of the Manufacturing Sector, tracks the number of regulations promulgated since 1981 that apply to manufacturers, and examines the particular burden of environmental regulations on the manufacturing sector. It finds that manufacturers have been subject to 2,183 unique regulations since 1981, of which 972 (or 45 percent) were EPA rules.

In fact, according to the MAPI report, EPA imposes the largest number of regulations on the manufacturing sector, followed by Departments of Transportation (880 rules), Labor (214 rules), and Energy (106 rules). Figure 1 illustrates the number of total rules affecting manufacturers from EPA, DOT, DOL, and DOE.

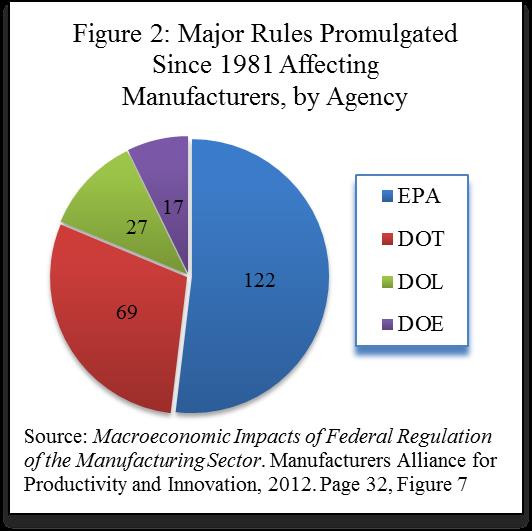

A “major” rule is a rule which the Administrator of OIRA has determined will have an annual effect of $100 million or more, will cause a major increase in costs or prices for consumers, or have significant adverse effect on competition, employment, investment, productivity, innovation, or trade.10 EPA leads the other agencies both in total rules affecting manufacturers and in major rules affecting manufacturers.

OMB’s data, as identified in the MAPI report, also point to the cumulative impact on manufacturers of these major rules. Figure 2 illustrates the major rules promulgated since 1981 from multiple agencies that affect manufacturers. According to MAPI’s aggregation of OMB data, EPA leads with 122 major rules affecting manufacturers, followed by 69 major rules from DOT.

According to the MAPI aggregation of OMB data, the cost of major EPA rules affecting manufacturers is higher than the cost of major rules from all other agencies. Including major rules from 1993 to 2011, the costs of EPA major rules affecting manufacturers totaled $117 billion annually, more than twice as much as the cost of DOT, HHS, DHS, DOE and DOL major rules combined ($50 billion). According to the MAPI report, major regulations could reduce manufacturing output by up to 6.0 percent over the next decade, with the largest burden coming from EPA rules. It estimates GDP losses from this output reduction ranging from $240 billion to $630 billion in 2012 alone.

B. Regulatory Burden by Sector

Our analysis of a different dataset corroborates this concern that the manufacturing sector is particularly burdened by regulation generally, and regulations issued by EPA in particular. Using the RegData database11 developed by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, we compared regulatory constraints imposed on the manufacturing sector with constraints on three other sectors (utilities, health care and social assistance, and finance and insurance). RegData measures regulatory “constraints” by compiling the frequency of command words such as “must” and “shall not” in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), the text where final regulations are recorded. According to its developers, RegData “allow[s] for industry-specific quantification of federal regulation, permitting within-industry and between-industry analyses of the causes and effects of federal regulations.”12

Figure 3 graphs information compiled from the RegData database to track the change in regulatory constraints for four sectors starting in 1997, with a starting point of 1 for all industries measured. This measure of regulations suggests that the manufacturing sector is subject to a higher rate of growth in regulatory constraints than utilities, health care, or the finance and insurance sector.

Further breaking down the commands by section of the CFR allows us to examine the frequency of constraints generated by environmental regulations relative to other regulations. Figure 4 shows increases in constraints in Title 40: Protection of the Environment versus three other Code of Federal Regulations titles spanning energy, labor, and transportation. This comparison suggests that the increases in regulatory constraints from environmental regulation by far outpace increases in regulatory constraints from energy, labor, and transportation regulations, further highlighting the importance of EPA’ retrospective review efforts.

Figure 5 shows the growth in Title 40 regulatory constraints applicable to manufacturers compared to the average growth in Title 40 regulatory constraints that apply to all industries (including to the manufacturing sector). According to this dataset, manufacturers have consistently shouldered a higher burden from environmental regulation than most other industries. The disparity of this burden is especially apparent after the year 2008, when Title 40 regulatory constraints applied to manufacturers leapt ahead of Title 40 regulatory constraints applied to all other industries. These increases in regulatory constraints and the burdens that accompany them invite a close look at the progress and efficacy of EPA’s retrospective review efforts to reduce regulatory burdens.

IV. Effects of EPA’s Retrospective Review Implementation

In January, 2013, EPA released an EO 13563 Progress Report listing 45 different regulatory actions both planned and underway to review existing rules. We were able to classify these regulatory actions into separate categories, based on the primary purpose of the regulatory action as described in the progress report or in the Federal Register for completed actions. It should be stressed that for the majority of these regulatory actions, the only information available for the purposes of classification is the information provided in EPA’s Progress Report. Because these are short descriptions that do not always contain all relevant information, we relied on descriptions in the proposed/final rule text where available to allow for the most accurate classification possible based on the available information.

We classified each action into one of the following categories:

- ·Paperwork reductions: Actions classified as “Paperwork Reductions” are those that reduce reporting and recordkeeping obligations, or initiate a transition from paper to electronic reporting.

- ·Streamlining: “Streamlining” actions are those that develop uniform standards or improve coordination.

- ·Updating Regulatory Requirements: “Updating Regulatory Requirements” includes actions that modify existing standards to better reflect technology or best practices.

- ·Reduced Burden: “Reduced Burden” includes regulatory actions that EPA states will reduce some costs to regulated entities by reducing existing regulatory requirements.

- ·Additional Burden: “Additional Burden” refers to actions that have cost increases for the regulated entity.

- ·Other: This classification includes regulatory actions that primarily increase transparency, reduce testing burdens, integrate planning, or commission studies.

- ·None: Refers to one action from EPA’s Progress Report, which EPA does not expect to have an impact on the regulated community.

Some of these classifications may be subject to change, as the final regulatory action may be very different than it was described in the EPA’s Progress Report. For example, the first regulatory action listed in EPA’s progress report (EPA’s Tier 3 proposed rule, RIN 2060-AQ86) is described as an action “where recordkeeping and reporting obligations can be modified to reduce burden,” and based on this description could be classified primarily as a Paperwork Reduction. However, after the text of EPA’s Tier 3 proposal became available, it was clear that the rule would incur substantial new costs without providing offsetting paperwork reduction benefits. Therefore, based on the text of the proposed rule, we categorized the Tier 3 rule as an Additional Burden.

Appendix A of this paper contains each of the regulatory actions in EPA’s January 2013 Progress Report, along with how each action was classified using the above categories.

The most prevalent regulatory actions EPA listed in this report fall into the category of Paperwork Reductions, which comprise 38 percent of all actions. As can be seen in Figure 6, Updating Regulatory Requirements and Other occur with the next highest frequency, at 15 percent, and Streamlining follows at 13 percent.

None of the 7 listed Updating Regulatory Requirements actions have an accompanying savings or cost estimate, and only one-third of the 17 Paperwork Reductions have any savings or cost estimate, making the effect of these actions difficult to estimate. Even for actions initiating Reduced Burdens—the primary goal of this retrospective review—EPA provided savings estimates for only half.

In fact, EPA provides no estimate of savings for the majority of its listed actions, making it difficult to gauge expected burden reduction. As shown in Figure 7, EPA did not include any savings or cost estimate for 60 percent of the regulatory actions listed in its progress report.13 Less than one-third of the regulatory actions that EPA lists have any cost or savings information, and of those, 31 percent include cost increases.14 Addition-ally, EPA anticipates 11 percent of the actions in its progress report will have no impact on regulatory burdens.

V. Will EPA’s Efforts Reduce Regulatory Burdens on Manufacturers?

Of the regulatory actions listed in EPA’s progress report, just over half target rules that burden manufacturers. Of these, EPA provides no cost or savings information for nearly half. Of the 42 percent of actions for which EPA quantifies costs or savings, 40 percent are estimated to increase costs to manufacturers.15 In fact, all of EPA’s regulatory review actions which increase costs will fall to manufacturers.

As impact estimates are only available for 42 percent of the regulatory actions affecting manufacturers in EPA’s progress report, this may understate the burden on the manufacturing sector. Because EPA did not provide cost or savings information for the remaining 46 percent, it is unclear whether any of those regulatory actions will reduce or increase the burden on manufacturers. The majority of regulatory review actions that will affect manufacturers are paperwork reductions which, while meaningful, do not substantially reduce regulatory burdens.

EPA has estimated that the total five-year savings from all review actions either underway or already completed is $1.5 billion—1.3 percent of EPA’s annual regulatory burden on the manufacturing sector. Even if all of these reforms were targeted at manufacturers, the effect is not substantial enough for EPA to claim credit for seriously reducing regulatory burdens on heavily-burdened sectors, such as manufacturing.

Conclusion

An examination of EPA’s retrospective review plan and progress report does not reveal the unprecedented cost savings and burden reductions for which many observers had hoped. Only one-fifth of the regulatory actions in EPA’s retrospective review progress report are expected to reduce costs. EPA provides no information on the effects of the majority of its retrospective review actions. It expects 11 percent of them will have no effect, and a number of regulatory actions will actually increase burdens on regulated entities.

Of the rules affecting manufacturers, one-quarter will reduce costs. EPA does not indicate whether half of the regulatory actions affecting manufacturers will increase costs, reduce costs, or have any impact at all, making it difficult to gauge whether EPA is successfully reducing excessive burdens on the regulated public. Additionally, all of the regulatory review actions which increase costs will fall to manufacturers, adding to the already significant regulatory burdens which exist in that sector.

*Sofie Miller is a Policy Analyst at The George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center. She would like to thank Art Fraas, Susan Dudley, and Randy Lutter for their rigorous comments and suggestions on this working paper. The help of Art Fraas in particular was crucial to the development of this idea and the many drafts that led to this paper. Additionally, she would like to thank Patrick McLaughlin for developing the RegData database and for answering her questions about it in such a timely manner, and Sam Batkins for making his research available.This article is adapted from a working paper for the Regulatory Studies Center at George Washington University. It reflects the views of the author, and does not represent an official position of the GW Regulatory Studies Center or the George Washington University. The Center’s policy on research integrity is available at http://research.columbian.gwu.edu/regulatorystudies/research/integrity.

Endnotes

1 United States Office of Management and Budget. Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Progress in Regulatory Reform: 2004 Report to Congress on the Costs and Benefits of Federal Regulations and Unfunded Mandates on State, Local, and Tribal Entities. [Washington, DC]: Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, 2004.

2 Macroeconomic Impacts of Federal Regulation of the Manufacturing Sector. Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation, 2012. Print.

3 Executive Orders governing regulatory oversight have generally not covered “independent regulatory agencies” (such as the Federal Communications Commission, the Securities and Exchange Commission, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission).

4 Office of Management and Budget. Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. MEMORANDUM FOR THE HEADS OF EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTS AND AGENCIES, AND OF INDEPENDENT REGULATORY AGENCIES. By Cass Sunstein.

5 Government Accountability Office. Regulatory Reform Agencies’ Efforts to Eliminate and Revise Rules Yield Mixed Results : Report to the Chairman, Committee on Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate. By L. Nye Stevens. Washington, D.C.: Office, 1997. Print.

6 Crain, W. Mark, and Thomas D. Hopkins, 2001. The Impact of Regulatory Costs on Small Firms. U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, www.sba.gov/advo/research/rs207 tot.pdf; United States. Office of Management and Budget. Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Progress in Regulatory Reform: 2004 Report to Congress on the Costs and Benefits of Federal Regulations and Unfunded Mandates on State, Local, and Tribal Entities. [Washington, DC]: Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, 2004.

7 Macroeconomic Impacts of Federal Regulation of the Manufacturing Sector. Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation, 2012. Print.

8 Ibid. 3

9 Regulatory Reform of the U.S. Manufacturing Sector. [Washington, DC]: Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, 2005. Print.

10 5 U.S.C. §804(1), Congressional Review Act: Definitions.

11 Al-Ubaydli, Omar and McLaughlin, Patrick A., RegData: A Numerical Database on Industry-Specific Regulations for All U.S. Industries and Federal Regulations, 1997-2010 (July 3, 2012). George Mason University Mercatus Center Working Paper No. 12-20. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2099814

12 McLaughlin, Patrick, and Omar Al-Ubaydli. “RegulationData.org.” Home. The Mercatus Center, 2012.

13 The regulatory actions which included a savings or cost estimate are those which, in the progress report or in the regulatory docket, EPA specified quantitative measures for either savings or costs incurred by the action. Some of these actions did not have any quantitative measures included in EPA’s progress report, but quantitative measures could be found in the regulatory text, accompanying RIA, or in EPA’s previous progress reports. To see how these regulatory actions were categorized, refer to Appendix A of this paper.

14 This includes one rule which developed uniform standards for equipment leaks (RIN 2060-AR00) that incurred both savings and costs to regulated entities.15 See supra note 14.

16 These are the author’s classifications based on the information provided in EPA’s report, EO 13563 Progress Report, January 2013. Where regulatory actions were published elsewhere (e.g. Federal Register, Unified Agenda), those sources were also used for the classifications in this appendix. The regulatory actions which include a savings or cost estimate are those which, in the progress report or in the regulatory docket, EPA specified quantitative measures for either savings or costs incurred by the action. Some of these actions did not have any quantitative measures included in EPA’s progress report, but quantitative measures could be found in the regulatory text, accompanying RIA, or in EPA’s previous progress reports. In the Cost/Savings column, red text indicates a cost increase, and green text indicates a cost savings. One rule, which developed uniform standards for equipment leaks (RIN 2060-AR00), incurred both savings and costs to regulated entities, and features both red and green text.

Appendix A: Classification of Rules in EPA’s January 2013 Progress Report16

|

EPA Retrospective Review Progress Report, January 2013 |

|||||||

|

RIN |

Description |

Sector |

Type |

Reasoning |

Cost or |

Cost/Savings |

|

|

2060-AQ86 |

Tier 3 vehicle & fuel standards |

Manufacturing |

Additional burden |

See “Cost/Savings” |

Yes |

$3.4 billion in additional costs yearly, with no monetized savings from paperwork reduction |

|

|

2060-AP66 |

Using optical gas imaging to streamline leak detection |

Manufacturing |

Stream-lining |

Allows multiple pieces of equipment to be monitored simultaneously |

No |

NA |

|

|

2060-AR00 |

Development of uniform standards for equipment leaks |

Manufacturing |

Stream-lining |

Develops and consolidates uniform standards for controlling equipment leaks |

Yes |

Savings of $6,780 - $31,400/year, also thousands in annualized costs and capital costs |

|

|

NA |

Voluntary water quality improvement |

Agriculture |

Other |

Develops voluntary standards for agriculture |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Prioritization of chemicals for workplace risk assessment |

Manufacturing |

Reduced Burden |

Reduced testing burdens |

No |

NA |

|

|

2070-AJ75 |

Online reporting of health & safety data (eTSCA Reporting) |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Electronic reporting |

Yes |

Savings of $66,834/year |

|

|

NA |

Improve NPL transparency, give localities more input |

State & Local Government |

Other |

Increased transparency |

No |

NA |

|

|

2040-AF25 |

NPDES permit process evaluation |

State & Local Government |

Updating regulatory require-ments |

Revise or repeal outdated or ineffective requirements for wastewater facilities |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Evaluating new approaches to maintaining clean water |

State & Local Government |

Other |

Efficacy |

___ |

No impact |

|

|

NA |

Integrated planning for municipal wastewater management |

State & Local Government |

Other |

Integrated planning approach |

No |

NA |

|

|

2060-AQ54 |

Harmonizing CAFÉ compliance requirements between DOT and EPA |

Manufacturing |

Additional burden |

Additional burden for the regulated entities (manufacturers) with benefits accruing elsewhere |

Yes |

Costs of between $134 billion and $140 billion |

|

|

2060-AQ41 |

Coordinating multiple air pollutant technologies |

Manufacturing |

Additional burden |

Additional burden through streamlining technologies |

Yes |

Nationwide capital costs of $5.9 million plus additional nationwide $2.1 million/year. Loss in economic welfare of $1 million for producers |

|

|

2060-AO60 |

Eliminate some NSPS reviews that would not result in environmental benefit |

Manufacturing |

Reduced burden |

Reduced testing burdens |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Simplifying and clarifying CAA Title V permitting programs |

Manufacturing |

Reduced burden |

Reduced permitting costs |

Yes |

Cost savings of $200 - $300 per permit |

|

|

NA |

Technology assessments in new rulemakings to encourage innovation |

Manufacturing |

None |

“This action is not designed to reduce costs or information burdens” |

___ |

No impact |

|

|

NA |

Improving regulatory cost estimates ex-ante by reviewing ex-post cost information |

None |

Other |

Study |

___ |

No impact |

|

|

2060-AQ97 |

Elimination of redundant gas station regulations |

Retail |

Reduced burden |

Eliminates requirements for gas stations to use redundant technology |

Yes |

Cost savings of $91 million total over the long-term |

|

|

2060-AP06 |

Updates to the NSPS for Grain Elevators |

Agriculture |

Updating regulatory require-ments |

Definitional change to ensure consistent application of standards |

No |

NA |

|

|

2050-AG20 |

Replace system for hazardous waste shipment with electronic system |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Electronic reporting |

Yes |

Paperwork burden reduction of $77 million - $209 million/year |

|

|

NA |

Electronic site ID form |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Electronic reporting |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Review of consumer confidence reports for drinking water regulations |

State & Local Government |

Other |

Transparency |

Yes |

Cost savings of $1 million/year in postage and paper costs |

|

|

NA |

Reduce state government reporting burden for water quality |

State & Local Government |

Paperwork reduction |

Identify approaches for reducing burden of water quality reporting requirements |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Export notification for chemicals and pesticides |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Changing standards for the reporting of chemical and pesticide exports |

___ |

No Impact |

|

|

NA |

Seek public feedback on the water quality trading policy |

Manufacturing |

Other |

Seek feedback on adoption of market-based approaches for Water Quality Trading |

___ |

No Impact |

|

|

2040-AF16 |

Review water quality standard to improve efficacy |

State & Local Government |

Updating regulatory require-ments |

Review of water quality standard to improve effectiveness |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Improvements to the SIP development process |

State & Local Government |

Paperwork reduction |

Reduce number of hard copies, minimize other paperwork requirements |

Yes |

Cost savings of $165,000 - $180,000 per year for affected states |

|

|

2040-AF15 |

Review and revision of Lead and Copper Rule |

State & Local Government |

Updating regulatory require-ments |

Simplify and clarify drinking water system requirements |

No |

NA |

|

|

2050-AF08 |

Revise threshold planning quantities for extremely hazardous substances |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

New threshold would allow facilities to have more hazardous materials on-site before reporting requirements are triggered |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Review of pesticide registration process |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Bundling chemicals for registration reviews reduces net paperwork |

No |

NA |

|

|

2070-AJ20 |

EPA regulations on required trainings for pesticide applicators |

Agriculture |

Stream-lining |

“Savings may result from streamlining activities which could reduce the burden on the regulated community by promoting better coordination” |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Review of guidance on PCB uses and cleanup |

Construction |

Updating regulatory require-ments |

EPA will review existing requirements to update and harmonize |

No |

Docket ID: EPA-HQ-RCRA-2011-0847 |

|

|

NA |

Review of regulations concerning pharmaceutical containers |

Retail |

Paperwork reduction |

New threshold for generator status would result in reduced paperwork |

No |

NA |

|

|

2050-AG39 |

Review of pharmaceutical waste data for rulemaking |

Retail |

Updating regulatory require-ments |

Review of data to inform rule-making updating waste management |

No |

NA |

|

|

2050-AG72 |

Hazardous waste requirements for retail products |

Retail |

Updating regulatory require-ments |

“EPA intends to analyze relevant information to identify what the issues of concern are for retailers, what materials may be affected, what the scope of the problem is, and what options may exist for addressing the issues.” |

No |

NA |

|

|

2040-AF29 |

Revise National Primary Drinking Water Regulations |

NA |

Stream-lining |

Multiple contaminants will be grouped into one regulation to streamline measurement and control |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Coordinate RFA §610 reviews with retrospective reviews |

EPA |

Stream-lining |

Section 610 reviews will be coordinated with other reviews to save agency resources |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Electronic reporting for hazardous waste exports |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Electronic reporting |

Yes |

$33,000 in cost savings to reporting entities in reduced courier fees and QA/QC costs. |

|

|

NA |

Convert financial assurance paper reporting to electronic |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Standardized electronic reporting across programs |

No |

Paperwork burden hours estimated, but cost/savings information is currently unidentified |

|

|

NA |

Hazardous waste e-Manifest |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Electronic reporting for tracking hazardous waste shipments |

Yes |

Implementation of e-Manifest could result in annual cost savings exceeding $75 million |

|

|

NA |

National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) e-reporting |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Electronic reporting |

Yes |

Permittees are estimated to save $1.1 million annually, and EPA $0.7 million annually. |

|

|

NA |

Pilot integrated portal |

Manufacturing |

Stream-lining |

Creation of an integrated portal to streamline reporting from regulated entities |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

Changes to pre-construction permitting |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

110,000 hours of paperwork burden expected to be reduced |

No |

Paperwork burden hours estimated, but cost/savings information is currently unidentified |

|

|

NA |

CAA stationary source electronic reporting |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Electronic reporting |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

CAA Title V clarification |

Manufacturing |

Paperwork reduction |

Expected to reduce paperwork burden by 120,000 - 180,000 hours |

No |

NA |

|

|

NA |

e-Reporting for the public water system supervision program |

State & Local Government |

Paperwork reduction |

Electronic reporting |

No |

NA |

|