Volume 13: Issue 1

The Ohio Constitution of 1803, Jefferson's Danbury Letter, and Religion in Education

That all men have a natural and indefeasible right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of conscience; that no human authority can, in any case whatever, control or interfere with the rights of conscience;

That all men have a natural and indefeasible right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of conscience; that no human authority can, in any case whatever, control or interfere with the rights of conscience;

that no man shall be compelled to attend, erect or support any place of worship or to maintain any ministry against his consent; and that no preference shall ever be given by law to any religious society or mode of worship and no religious test shall be required as a qualification to any officer of trust or profit.

But, religion, morality and knowledge being essentially necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of instruction shall forever be encouraged by legislative provision, not inconsistent with the rights of conscience.

Introduction

These statements come from the Ohio Constitution of 1803. They are from Section 3, the religion section of Article VIII, the Bill of Rights.1 This last sentence of Section 3, which addresses education, is taken directly from a statement in the Northwest Ordinance, passed by the Continental Congress July 13, 1787, which provided the framework for the admission of Ohio to the Union.2 It is the contention of this paper that these words express widely-held attitudes in regard to church and state, as well as religion and education, in the early days of the United States.3

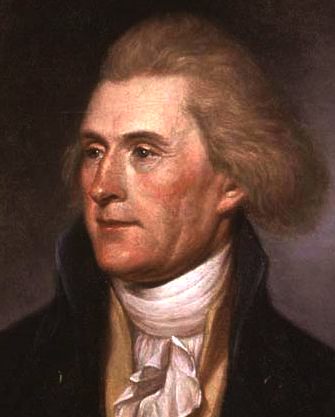

What gives added support to this argument is the political background of those who pushed for Ohio statehood and led the Constitutional Convention at the territorial level and those who supported statehood and approved the work of the Convention at the national level. At both levels the Republican Party, the party of Thomas Jefferson, was in the majority. Statehood came to Ohio by congressional vote and approval by President Jefferson on February 19, 1803.

The reason to attach importance to the political setting of the drafting and approval of the Ohio Constitution is that shortly before—in January 1802—Jefferson had written a letter to the Danbury Baptists of Connecticut interpreting the absence of religious establishment at the national level as a “wall of separation between church and state.” Such a wall, according to the letter, was to protect individuals from government interference in matters of faith and worship. Specifically, of course, Jefferson was referring to the First Amendment, which forbids Congress from enacting laws respecting an establishment of religion.4

This paper addresses the extent to which Jefferson’s support for the Ohio Constitution implies a lessening of the significance of his Danbury letter as an interpretation of original intent regarding the relationship of church and state and of religion and education. The education statement in the religion article of the Ohio Constitution does not seem to provide for a wall of separation between government, education, and religion.

The paper first examines the 1948 McCollum case in the United States Supreme Court. In McCollum, the Court rejected arguments defending the constitutionality of allowing a limited accommodation for religion in schools. The arguments by the defendant school district show the persistence of attitudes associated with the education statement in the 1803 Ohio Constitution 145 years after its adoption, and 159 years after the First Congress under the new Constitution in 1789 adopted in toto the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.5 The paper then examines the background for the inclusion of this provision into the Northwest Ordinance, the issues associated with the movement toward the adoption of the 1803 Ohio Constitution, the politics surrounding the Danbury Letter, and the non-controversial nature of the education provision of the 1803 Ohio Constitution. Together, the existing scholarship on these topics suggests that the Ohio Constitution well represents a consensus regarding religion, state, and education in the early days of the Republic.

Early Intent: The Wall of Separation or the Ohio Constitution?

The current fame of the Danbury letter stems from the use of Jefferson’s metaphor of a “wall of separation” by the U.S. Supreme Court as the basic statement of original intent in two landmark cases in the 1940s that shaped subsequent court decisions.6 In the 1948 McCollum case, in an 8-1 vote, the Court declared as an unconstitutional violation of the principle of the separation of church and state a “released time” program in the Champaign, Illinois public schools.7 The Court rejected the school district’s argument for allowing some limited accommodation of religion in public education, which was the approach of the up-to-forty-five-minutes-a-week program of providing religious instruction in the elementary schools in Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish classes. The prevailing argument was that the program was conducted on school time and in school buildings, signaling government support for religion, and that it breached the wall of separation between church and state that the U.S. Constitution was designed to protect. The plaintiff claimed that the program by its nature created an embarrassment for non-participating pupils such as Terry McCollum, thereby violating such person’s right to be free of any religious involvement.

The proponents countered that the program was constitutional because there was no coercion to take part; rather, participation was voluntary, parental permission being necessary, and the classes were educational, not devotional or ceremonial; nor was tax money used. It did not favor one group over another. The Board of Education intended that all interested groups could have a class. Providing constitutional support for the “released-time” program, the defense cited the “no preference” principle set forth in early state constitutions as a basic statement of original intent, Ohio being one example.

The lawyers for the defendant school district contended that the U.S. Constitution was not designed to give the national government authority over such matters at the state and local level. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected this argument, reiterating its position in the Ewing case that the 14th Amendment incorporates the Establishment Clause, thus making it applicable to the states. However, if Section 3 of Article VIII of the Ohio Constitution rather than the Jefferson Danbury Letter’s wall of separation had been viewed as a statement of original intent, then the Supreme Court’s decision could have been more favorable to the defendants.

The program had been put in place to meet a secular goal of reducing juvenile delinquency in the Champaign community, on the assumption that religious influences tend to improve behavior and citizenship. This assumption links the “released-time” program with the assumptions of the education provision of the Northwest Ordinance and the Ohio Constitution and shows the persistence of the attitudes expressed by the provision. However, neither the provision nor its inclusion in the 1803 Ohio Constitution was cited at any time by any party involved with the case. Still, the defendant’s case, in essence, contended that the program did not have elements of a religious establishment and that it was “not inconsistent with the rights of conscience.”

The Northwest Ordinance and Its Statement on Education and Religion

The Ordinance created the Northwest Territory and permitted the formation of three to five states in the territory. As people moved into this territory, there eventually were formed, with final approval of Congress and the President, the Midwest states of Ohio (1803), Indiana (1816), Illinois (1818), Michigan (1837) and Wisconsin (1848).8

In Congress, Jefferson had a role in the process leading to the Northwest Ordinance, notably his leadership in developing some resolutions in 1784. However, he was not a member when Congress approved the Ordinance in 1787; neither was he a member when Congress proposed the Bill of Rights in 1789.

It is evident that one group and one individual provided the catalyst for the final shaping of the Northwest Ordinance.9 The group, based in New England, was the Ohio Company of Associates and the individual was Manasseh Cutler, the Company’s agent and lobbyist with Congress and a clergyman. Congress was willing to go along with the Company’s insistence on a strong, centralized colonial government committed to orderly development that would encourage its stockholders and other entrepreneurial and skilled people from the East to risk moving into a wilderness area full of dangers from Indians and unexplored terrain.

In later years Cutler was recorded as explaining why “the recognition of religion, morality and knowledge as the foundations of civil government were incorporated into the Ordinance.” It arose from the fact that “he was acting for associates, friends and neighbors who would not embark in the enterprise unless these principles were unalterably fixed.” He included the prohibition of slavery among these principles.10 In the writings on the development of the Ordinance, there is no evidence that the education statement was controversial.

It is generally held that the Constitution of Massachusetts was the starting point for the words in the Ordinance. The Calvinist-inspired Article III, in the Declaration of Rights, asserted that to secure “the happiness of a people and the good order and preservation of civil government essentially depends upon piety, religion and morality and [as] these cannot be generally diffused through a community but by the institution of public worship of God and of public instruction in piety, religion and morality . . . .”11

Obviously there was a substantial simplification in the process of settling on words in the Ordinance. Dropped was any reference to institutions of religion with their implications of an establishment of religion and religion requirements.

The Ordinance also contained a statement on religious liberties, which seems also to have been drawn from the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780.12 The statement reads: “No person demeaning himself in a peaceable and orderly manner shall ever be molested on account of his mode of worship or religious sentiments in the said territory.”

The Ohio Constitution of 1803

Ohio was the first state to be formed from the Northwest Territory, and it was the only state admitted to the Union during the eight years of Jefferson’s presidency.

The Ohio Constitution of 1803 was primarily the work of Republicans, at both the national and Ohio levels.13 Federalists, in Ohio as well as nationally, were a waning influence following the elections of 1800, which elected Jefferson President and gave Republicans the majority in Congress.

The governor of the part of the Northwest Territory that was to become the State of Ohio was Arthur St. Clair. As a Federalist, St. Clair was skeptical of representative democracy and specifically of the capability of frontiersmen to assume the reins of government, and thus was inclined to continue to support orderly development by means of centralized control as prescribed in the Northwest Ordinance. It was the desire to throw out an executive unaccountable to the people that broadened the demand for statehood and stimulated the growth of a group of politically-active Republicans to oppose him. Frontier Ohio was heavily populated by people from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Kentucky, places where sentiments favored individualism, local control, and democracy.

St. Clair’s strategy was to split the Ohio territory into an eastern and western part. As Republican sympathizers were particularly strong in south-central Ohio, this boundary change would dilute their strength. It was this plan to divide Ohio that caused an outcry by Ohio Republicans and motivated them to press national party leaders for statehood as soon as possible and for removing St. Clair from the office of governor. They emphasized that statehood for Ohio under existing territorial boundaries would very likely create two Republican Senators and one Republican House member and thus add three electoral votes for Republican presidential candidates—a particularly appealing argument given the closeness of the 1800 presidential elections.

On March 4, 1802, Ohio Republicans sent an application to Washington seeking statehood.14 They sought a promise from the national government that it would continue to help finance schools as originally provided for in the Land Ordinance of 1785, which set up a system that created six-square-mile townships. Authored by Thomas Jefferson—one of his many statements supporting education—the Ordinance required that revenue from “section No.16 in every township, sold, or directed to be sold by the United States, shall be granted to the inhabitants of such township for the use of schools.”15 In support of this position, the Committee cited without comment the education statement in the Ordinance.

In direct response to the concerns of Ohioans seeking statehood, Congress passed the Enabling Act for Ohio, and Jefferson signed it on April 30, 1802. This signature occurred only four months after his sending his “wall of separation” letter to the Baptists in Danbury Connecticut. The Act rejected any splitting of Ohio, set the guidelines for constitution-making, and supported the educational use of Section 16 revenues.16 However, neither the report of the Committee of Ohioans requesting congressional authorization for a constitutional convention nor the Enabling Act by Congress allowing the convention contained any comment or elaboration on, objections to, or justification for any part of the statement in the Ordinance that addresses the general content of education (religion, morality, and knowledge) or its purposes (happiness and good government).

Republicans carried four-to-one the October election for delegates to the constitutional convention thanks to the vote of a public already favorable to the party of Jefferson. At the convention, in a reversal of positions, St. Clair took a Republican position on this issue and strongly defended states’ rights and strict construction. He argued that the national government under the Ordinance did not have the power to authorize a constitutional convention or to set conditions for its operation. He argued that such an initiative could only come from people in the territory of the proposed state. In approving the Enabling Act, Jefferson was also involved in a reversal of position. His 1784 resolutions stated that the procedure for calling a state constitutional convention be democratic and decentralized; thus, the call should come from the people in the territory seeking statehood.17

The Convention that met in November 1802 placed the education provision of the Northwest Ordinance in Section 3, the religion section, of the Bill of Rights. The constitution contained no separate article for education, indicating that religion was seen as an integral part of schooling. The journal of the Convention contains only the votes on various proposed provisions. The delegates left no record of the debates. There is nothing in the journal of the Convention indicating that any part of Section 3 was controversial.18

With only three additions, the education statement was taken word-for-word from the Northwest Ordinance. The additions were: 1) the word “But” precedes the statement, indicating that the framers of the Ohio Constitution thought that these words represented a different perspective from one or more of the previous parts of the Section; 2) the necessity of a role for religion, along with morality and knowledge, in education is enhanced to be “essentially” necessary; and 3) the General Assembly is given a role in encouraging schools as long as it actions are “not inconsistent with the rights of conscience.” The entire statement follows with the additions underlined: “But religion, morality and knowledge being essentially necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, school, and the means of instruction shall forever be encouraged by legislative provision not inconsistent with the rights of conscience.” Following the completion of their work in late November, the drafters submitted their constitution to Congress.19 Thereupon, Congress recognized the State of Ohio as a member of the Union, and President Jefferson approved statehood on February 19, 1803.

Jefferson’s Danbury Letter

In signing off on the Ohio Constitution, President Jefferson was by implication supporting its various provisions. Yet only a year earlier he wrote the now-famous letter to the Danbury Baptist Association of Connecticut that contained a strong statement of the individual’s right to liberty of conscience: “that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship . . . .” According to Jefferson, this right was set forth with the adoption of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which stated that Congress should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” The result was, according to Jefferson’s interpretation, the creation of a “wall of separation between church and state.”20

Jefferson’s letter was a response to one from the Baptist Association. The Association expressed dissatisfaction with the continuing establishment of the Congregational Church in the state, and the fact that those religious liberties Baptists did then enjoy were granted by the legislature and thus not inalienable rights. They hoped Jefferson’s support would help shape public opinion in their favor as they sought to break up the alliance of the Congregational Church and the General Assembly of Connecticut and thus overcome what they considered to be their subordinated position.21

According to Philip Hamburger, the Jefferson letter to the Danbury Baptists must be considered in the political context of the national presidential election of 1800. Jefferson had a reputation for anti-clerical attitudes, objecting to conventional and organized Christianity, questioning the civil value of religion, and sympathizing with deism and Unitarianism. His efforts to disestablish the Anglican Church in Virginia were widely known. Notable among the opponents to Jefferson were members of the establishment clergy in Connecticut, who tended to hold Federalist sympathies. In response, Jefferson’s Republican supporters in that state advocated the separation of church and state. They meant by “separation” that members of the clergy should not take part in any way in politics, arguing that politics and government were not their area of expertise. Given this context, writes Hamburger, the letter can be viewed as a political statement “written to assure Jefferson’s Baptist constituents in New England of his continuing commitment to their religious rights and to strike back at the Federalist-Congregational establishment in Connecticut for shamelessly vilifying him as an ‘infidel’ and an ‘atheist’ in the rancorous presidential campaign.”22

Jefferson wanted his statement to have a wide impact, and his words that an individual “owes account to none other for his faith or his worship” and “that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only and not opinion” surely found favor with these Baptists. They opposed establishment. They thought that laws should not require the payment of taxes to support religion, or to favor one religious group.

However, the Danbury Baptists failed to publicize and promote Jefferson’s response to them, very likely because the opinion held by Baptists and others was that people and the government itself should be subject to religious influences. Along with other religious groups, Baptists wanted the legislature to prohibit amusement, travel, and unnecessary labor on Sunday. Thus, a “wall of separation” was not their goal. As Hamburger states:

Tactically, dissenters could not afford to demand separation, for a potent argument against them had been that they denied the connection between religion and government—a serious charge in a society in which religion was widely understood to be the necessary foundation for morality and government. Nor could Baptists or other evangelical dissenters, whose preachers had long campaigned for religious liberty, accept separation’s implications that the clergy had no right to preach politics . . . . Many Baptists seem to have held that all human beings and all legitimate human institutions, including civil government, had Christian obligations, and some Baptists felt obligated to remind Americans and their government of their Christian duties . . . . At the very least, in their social attitudes, Baptists seem to have had no quarrel with the commonplace that religion was essential for morality, republican government and freedom.23

This “commonplace” found expression in the education provision of the Northwest Ordinance.

Recognizing the radical tone of the Danbury Baptist letter, Jefferson took measures to “protect himself from what he assumed would be a clerical onslaught.”24 After issuing his letter on Friday, January 1, 1802, two days later on Sunday, “contrary to all former practice,” he went to his first church service in the House of Representatives and “attended it consistently for the next seven years.” By attending church services in Congress, “Jefferson intended to send to the nation the strongest possible symbol that he was a friend of religion.”25 “Being . . . . as cautious in person as he was bold in his imagination, Jefferson balanced his anticlerical words with acts of personal religiosity.”26

The Baptists, understanding federalism, knew that the national government could not force disestablishment upon a state (or, for that matter, force an establishment) because to do so would violate the provision that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”27 Still, they wanted the President to make some sort of statement that would encourage disestablishment in those states where an establishment still existed, notably in their own state of Connecticut. Jefferson may have intended that the Danbury Baptists could interpret his letter to mean that a wall of separation is also the proper design of the relationship between state government and religion. But Jefferson seems to have realized that it is up to the states to bring about that relationship. According to Dreisback, “a careful review of Jefferson’s actions throughout his public career suggest [sic] that he believed as a matter of federalism, that the national government had no jurisdiction in religious matters, whereas state governments were authorized to accommodate and even prescribe religious exercises.”28 Supporting such distinct roles for the states is well in line with Jefferson’s reputation of favoring strict construction, states’ rights, and local autonomy.

The Education Provision’s Non-Controversial Character

As indicated, there is nothing in the official documents associated with the development and approval of the Ohio Constitution to indicate that the inclusion of the language from the Northwest Ordinance was in any way a contentious issue in general or among the various elements of the Republican Party, either in Ohio or in Washington. For example, Ruhl Jacob Bartlett, drawing mainly on the Annals of Congress, gives no indication that Congress in considering the Enabling Act had any concern about the inclusion of the education statement from the Ordinance in the petition for statehood from Ohio Republicans.29

Nor is there any such indication in books covering this period in Ohio history and cited in footnote 13 of this paper. None of them makes a reference to Section 3 in the Bill of Rights. Rather, they focus on how the constitution was a reaction to the centralization of authority of the governor under the Ordinance, thus creating a strong legislature and a weak executive and judiciary in Ohio. It limited the governor to two terms, denied him the veto power, and gave the legislature the power to appoint judges and approve all executive appointments.

For example, the biography of Thomas Worthington makes no reference to any record of a discussion of any specific provisions of the proposed constitution that Worthington or anyone else had with Jefferson when he was in Washington to lobby for statehood.30 Worthington was a leading Republican at the Convention and the Republicans’ principal liaison with Washington. He did write that the work of the Convention was well-received in Washington and that “our business is before a committee of Congress and I hope it will very soon pass through . . . .Our friends here are generally well pleased with our constitution.”31

Although very brief and subject to Federalist biases, the principal source of substantive information on Article 3 is the biography of Ephraim Cutler, written by his daughter Julia Cutler.32 A member of the committee on Article VIII, the Bill of Rights, Ephraim Cutler takes credit for preparing and introducing the provision relating to education and religion as well as to slavery. The son of Manasseh Cutler, Ephraim Cutler was a member of the minority Federalists in the Convention and shared his father’s support for public education, a religion-influenced civil morality, and strong opposition to slavery.33

The Cutler biography provides some evidence that Jefferson took an interest in several parts of the constitution. This book quotes the recollections of Jeremiah Morrow, recorded many years later, about an 1803 conversation this Ohio politician had with the President. Although commending the Ohio Constitution highly in its main features, Jefferson expressed several misgivings about it. The only two that stood out in Morrow’s recollections were the ones related to the structure of the judiciary and the exclusion of slavery. According to Morrow’s memory, Jefferson supported a proposal at the Convention allowing a male under the age of 35 and a female under 25 to be held in slavery in Ohio, and that Jefferson thought the total exclusion of slavery, the position finally adopted by the Convention, “would operate against the interests of those who wished to emigrate from a slave state to Ohio.”34 Cutler also claimed to have evidence of such support from his own observations at the Convention.35

A related issue that also generated much controversy was suffrage for black males, which lost by only one vote. The record of votes at the Convention indicated that there were also differences of opinion on the judicial article, annual or biennial sessions of the legislature, the submission of the constitution to the people for ratification, the salaries of officials, and qualification of voters. Not included among those matters upon which there was disagreement was the incorporation of the Ordinance’s education provision into the constitution.36

One could hypothesize that Jefferson and his supporters might have considered crafting wording to implement the wall of separation so recently endorsed by placing such words into the Ohio Constitution. However, support for these two constituency groups—the Danbury Baptists and the Ohio Republicans seeking a state constitution—called for distinct responses due to distinct and unrelated political circumstances.

For example, it is reasonable to assume that the widely-held view that religion was important as a foundation for morality and good government was also held by the strongly religious men who were centrally involved in creating the constitution for Ohio; and that they specifically wanted the education provision of the Ordinance to be included in the Ohio Constitution.37 Whatever the extent of Jefferson’s involvement with the shaping of the constitution, the predominant view of the day was that the First Amendment guaranteed that states had considerable leeway in how they related to religion. And Jefferson often supported states’ rights and local control.

Moreover, party conflict was not prominent at the Convention. Federalists presented themselves as friends of republican government, democracy, personal freedom, and local control. Cutler wrote that Federalists “wished to encourage democracy, by having townships to manage local business; and to encourage schools and education, by providing that it be imperative on the legislature to make laws for that purpose; and that all should enjoy perfect religious freedom, as their conscience should dictate.”38 Was this statement by Cutler and the language adopted in the religion section emphasizing freedom of conscience an effort to address Jefferson’s concerns for the rights of conscience, such as those expressed in the Danbury letter? Was this emphasis part of a compromise that gave Federalists and others what they wanted: authority for a governmentally-supported education system that gave religion a role in schooling? A reasonable assumption perhaps, but the scanty remembrances left by participants in the Convention provide no evidence of it. Further, a compromise seemed unnecessary. As indicated, party divisions in the Convention were not prominent. Cutler and his friends supported religious liberties and anti-establishment principles. Jefferson wanted to demonstrate that he was a friend of religion, and one could hypothesize he saw the inclusion of the words from the Ordinance as a chance to demonstrate such friendship.

Perhaps the inclusion of the Ordinance language was simply the sense that because the education provision was in the Ordinance, it should be in the constitution of a state formed from the Ordinance. However, those who wrote the constitutions for Indiana (1816) and Illinois (1818), the next two states to be formed from the Northwest Territory, did not include the education section from the Ordinance, even as they copied much from the other parts of the religion article of the Ohio Constitution.39

Conclusion

This article has examined the circumstances surrounding the development of two well-known statements on the role of religion in relation to government from early in the nation’s history. One is found in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, encouraging a role for religion in education; the other is Jefferson’s 1802 Danbury Baptist “wall of separation” letter. While the Ohio Constitution makes no reference to such a wall, it certainly rejects any kind of religious establishment, stating:

[N]o man shall be compelled to attend, erect, or support any place of worship or to maintain any ministry against his consent and that no preference shall ever be given by law to any religious society or mode of worship and no religious test shall be required as a qualification to any office of trust or profit.

As indicated, the Danbury letter, however, did not focus specifically on such anti-establishment principles, but rather on the right of conscience. This right was cited at the beginning of the religion section of the Ohio Constitution. A perceived tension between such a right and a role for religious influences in the schools is indicated by the word “But” in the Ohio constitution that precedes the statement taken from the Northwest Ordinance. However, they are not inconsistent, the constitution states, as long as implementation of the education provision is “not inconsistent with the right of conscience.”40

The education provision brought together two widely-held perspectives. One supported the individual’s liberty of religious conscience—a perspective emphasized by Jefferson’s letter. The second wanted religion to exert moral influence on people and government, specifically through schools and the means of instruction—a perspective emphasized by religious leaders in New England.

There is nothing in the official documents associated with the development and approval of the Ohio Constitution to indicate that the inclusion of the language from the Ordinance was in any way a contentious issue in general or among the various elements of the Republican Party, either in Ohio or in Washington. Nor is there any such indication in the books covering this period in Ohio history or in the scanty recollections of participants.

In summary, the implication of the information provided in this paper is that the single best statement of early intention in regard to church and state, religion, and education is a little-known and seldom-cited provision in an early state constitution—Section 3, the religion section, in the Bill of Rights of the Ohio Constitution of 1803. It includes Jefferson’s central perspective, but not his “wall of separation” interpretation in his letter to the Danbury Baptists. In contrast to Jefferson’s letter, it was an official act of government. Thus, according to the evidence and analysis presented in this paper, Section 3 represents the consensus of the early days of the United States.

* David Scott has a Ph.D. in political science from Northwestern University and has taught American government courses at a number of Illinois colleges and universities. In retirement he was the president of the Illinois State Historical Society and attended Federalist Society meetings in St. Louis.

Endnotes

1 Constitution of the State of Ohio—1802, in From Charter to Constitution, 5 Ohio History 132-153 (D.J. Ryan ed., 1897). The work of the conventions concluded in November 1802. February 19, 1803 was the date that Jefferson approved statehood.

2 Article the First, Section 14, An Ordinance for the government of the territory of the United States North west of the river Ohio, passed by Congress, July 13, 1787, in The Northwest Ordinance 1787: A Bicentennial Handbook 56-57 (Robert M. Taylor, Jr. ed., 1987).

3 John Eastman cites this statement in the Ordinance as perhaps the most significant of the many statements made in the founding period regarding the importance of morality and virtue underlying republican self-government. John Eastman, The Establishment Clause, Federalism and the States, Engage, May 2003, at 55-58.

4 U.S. Const. amend. I.

5 An Act to provide for the government of the territory North west of the river Ohio, approved August, 1789, First Congress, Sess I, ch. 8. 50-53.

6 Everson v. Bd. of Educ. of Ewing Twp., 330 U.S. 1 (1947); McCollum v. Bd. of Educ. of Champaign Dist. 71, 333 U.S. 203 (1948).

7 See David W. Scott, Religion in the Schools: Illinois Courts v. United States Supreme Court, 100 J. Ill. St. Hist. Soc’y 328, 328-359 (2007-2008). This article is an extensive analysis of the issues involved in the McCollum case and the major precedent used by the plaintiff, People ex rel Ring v. Board of Education of District 24, 245 Ill. 334 (1910).

8 There was a flurry of books and articles around 1987 generated mainly by Midwestern universities recognizing the Ordinance’s 200th anniversary. Treating the Ordinance in substantial detail are Peter S. Onuf, State and Nation: A History of the Northwest Ordinance (1987); and The Northwest Ordinance 1787, supra note 2.

9 See Ray A. Billington, The Historians of the Northwest Ordinance, 40 J. Ill. St. Hist. Soc’y 402, 402-408 (1947).

10 William Parker Cutler & Julia Parker Cutler, Life, Journal and Correspondence of the Rev. Manasseh Cutler, Vol. I, at 344-45 (1888).

11 Mass. Const. of 1780, art. III, Declaration of Rights.

12 See id. art. II, Declaration of Rights (“And no subject shall be hurt, molested or restrained . . . . for worshiping God in the manner and season most agreeable to the dictates of his own conscience, or for his religious profession or sentiments, provided he doth not disturb the public peace or obstruct others in their religious worship.”).

13 The following five books deal in detail with the events leading to the adoption of the Ohio Constitution of 1803: Onuf, supra note 8, at chaps. 4, 5; Randolph Chandler Downes, Frontier Ohio, 1788-1803, at chaps. V, VI, Vll (1935); R. Douglas Hurt, The Ohio Frontier: Crucible of the Old Northwest, 1720-1830, at chap. 9 (1996); Andrew R.L. Cayton, Frontier Republic: Ideology and Politics in the Ohio Country, 1780-1825, at chap. 5 (1986); and Alfred Byron Sears, Thomas Worthington: Father of Ohio Statehood, at chaps. vi, v (1958).

14 Application to Erect the Northwest Territory into a State, in From Charter to Constitution, supra note 1, at 69-73.

15 An Ordinance for ascertaining the mode of disposing Lands in the Western Territory, approved by Congress, May 20, 1785, in Onuf, supra note 8, at 22-24.

16 Enabling Act for Ohio, in From Charter to Constitution, supra note 1, at 74-78.

17 See Onuf, supra note 8, at 47.

18 First Constitutional Convention, Convened November 1, 1802, in From Charter to Constitution, supra note 1, at 80-131. That liberty of conscience was paramount and any aspect of a religious establishment was fully rejected by the Convention is indicated by a proposal at the Convention to strike from a draft of the Bill of Rights a prohibition on a religious test. To be substituted was the following: “No person who denies the being of a God or a future state of rewards and punishment shall hold any office in the civil department of this State.” The proposal was overwhelmingly defeated thirty to three. Id. at 111. The U.S. Constitution also has a prohibition on a religious test. See U.S. Const. art. VI. However, the original Constitution, as ratified, did not contain any other anti-establishment principles, such as those included in the 1803 Ohio Constitution.

19 Constitution of the State of Ohio—1802, in From Charter to Constitution, supra note 1, at 132-153.

20 The discussion that follows relies heavily on Chapter 7 of Philip Hamburger, Jefferson and the Baptists: Separation Proposed and Ignored as a Constitutional Principle, Separation of Church and State 144-189 (2002).

21 The group wrote that “our hopes are strong that the sentiments of our beloved President, which have had such genial Effect already . . . . will shine and prevail through all these States and all the world till hierarchy and tyranny be destroyed from the Earth . . . .” Id. at 158. The entire letter is at page 158, and Jefferson’s full response is at page 161.

22 Daniel Dreisback, Thomas Jefferson and the Wall of Separation Between Church and State 29 (2002), cited in Douglas G. Smith, Thomas Jefferson’s Retrospective on the Establishment Clause.. 26 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 369, 378 n.35 (2003).

23 Hamburger, supra note 20, at 177-180.

24 Id. at 162.

25 James H. Hutson, Religion and the Founding of the American Republic (1998), cited in Hamburger, supra note 20, at 162.

26 Id.

27 U.S. Const. amend I. The Danbury Baptists recognized, in their letter seeking support, that the President is not Congress and that the national government cannot “destroy the laws of each state.” See Hamburger, supra note 20, at 158.

28 Dreisback, supra note 22, at 59-60, cited in Smith, supra note 22, at 374.

29 Ruhl Jacob Bartlett, The Struggle for Statehood in Ohio, 32 Ohio History, supra note 1, at 472-506.

30 Sears, supra note 13, at chap. x. Sears states:

In the movement to secure Ohio’s admission to the Union and in the framing of an enlightened and democratic constitution, which excluded slavery, banished executive tyranny and safeguarded private and public liberties in a comprehensive bill of rights, no one displayed greater leadership than Thomas Worthington.

See id. at Preface, vii.

31 See David Meade Massie, Nathaniel Massie: A Pioneer of Ohio 220 (1896). Perhaps upcoming volumes of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson being published by the Princeton University Press will bring to light information on issues related to the education provision. According to the Press, “Jefferson’s letters are the largest component of the more than 70,000 documents that have been assembled as photocopies from over 900 repositories and private collections worldwide.” The first volume was published in 1950. The two most recent volumes are Volume 36: 1 December 1801 to 3 March 1802, and Volume 37: 4 March 1802 to 30 June 1802, which cover the period of the movement toward statehood through the Enabling Act. Neither volume contains papers addressing the education provision or any other aspect of the planned constitution for Ohio.

32 See Julia P. Cutler, Life and Times of Ephraim Cutler (1912).

33 Although Convention members were willing to follow Cutler’s lead in adopting a constitutional call for the legislature to encourage school, they were certainly aware that Ohioans were not ready to take the first steps in support of a state public school system. Such steps did not occur until the 1820s. In the meantime, schooling was strictly a local and often private matter with religious content common.

34 See Cutler, supra note 32, at 74.

35 Id. at 75. Such support by Jefferson goes against his reputation as an opponent of slavery. For example, he was the only Southerner to vote for an anti-slavery proposal when the 1784 resolutions were under consideration. Perhaps, however, Jefferson had in this case reversed his previous anti-slavery positions in response to pressure from slave-holding interests in his home state. On the other hand, it is possible that his position was misconstrued as part of the standard political rhetoric of Ohio Federalists that Virginia Republicans wanted statehood in order to extend slavery to Ohio. On this charge, see Hurt, supra note 13, at 281.

36 See Bartlett, supra note 29, at 498-501; Isaac Franklin Patterson, The Constitutions of Ohio; Amendments and Proposed Amendments 29-30 (1912).

37 On the strong religious beliefs of Thomas Worthington and other Ohio Republican leaders, see Cayton, supra note 13, at 58-59, and Sears, supra note 13, at 103-04. They tended to be Methodists, not Calvinists.

38 See Cutler, supra note 32, at 69-70.

39 Ind. Const. of 1816, art. I, § 3; Ill. Const. of 1818, art. VIII, §§ 3, 4.

40 The provision supporting religious influence in schools was retained in the 1851 Ohio Constitution with somewhat different wording: “[R]eligion, morality and knowledge, however, being essential to good government, it shall be the duty of the General Assembly to pass suitable laws . . . and to encourage schools and the means of instruction.” See Ohio Const. of 1851, art I, § 7.