Volume 13: Issue 1

Bounty Hunters and the Public Interest - A Study of California Proposition 65

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Adopted by California voters in 1986, Proposition 65 was a revolutionary measure in a number of respects. Although titled “Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act,” the scope of the law was much broader than water pollution. The goal of the law was to protect Californians from exposure to cancer-causing substances and reproductive toxins. In addition to prohibiting introduction of such chemicals into the water, the law also required warnings so people could choose to avoid areas where they might come in contact with chemicals known to cause cancer or reproductive harm. Immediately after passage, the new law required the state to compile a list of substances known to cause cancer and reproductive toxins. This list has now grown to nearly 900 different substances. Because the law mandates warnings that allow consumers to avoid exposure to these chemicals, backers of the measure argued that it would reduce the incidence of cancer and other health problems in California.

The law had a darker side, however. Instead of leaving enforcement to politically-accountable public officials like the District Attorney and Attorney General, Proposition 65 allowed enforcement by “bounty hunters.”1 These bounty hunters could be anyone from concerned citizens or environmental groups, to groups merely seeking to cash in on a quick payoff in attorney fees and civil penalties. Indeed, the law specifically provided that a portion of the civil penalties collected in bounty-hunter actions would be paid to the group bringing the lawsuit, rather than the public treasury. These provisions provided a powerful monetary incentive to file claims alleging California businesses have failed to provide appropriate warnings—whether or not those claims had any merit.

Private litigants have not been satisfied, however, with their share of the civil penalty. With the approval of former California Attorney General Bill Lockyer, organizations that bring this type of litigation have switched their focus to requiring payments directly to themselves or another organization “in lieu” of paying a civil penalty. Monies that would have gone to the public treasury to pay for public enforcement of Proposition 65 have instead been diverted to private organizations so that they could pursue their own aims—whether those be appropriate enforcement or pursuit of future payments (or both). What is missing from the debate on Prop 65 is a thorough and thoughtful examination of the bounty hunter provision and the legality of diverting civil penalties from the state treasury to the private accounts of environmental groups.

This paper will lay out a succinct argument focused on the purpose and intent of Proposition 65 as originally enacted. Given these purposes, the paper will then examine the record of settlements under the law—how much is collected from businesses and to whom it is paid. Next, this paper will analyze the legality of the move to divert civil penalties from the state treasury to the private accounts of the litigating organizations. Finally, this paper offers recommendations to reform Proposition 65 litigation.

HISTORY AND PURPOSES OF PROPOSITION 65

Proposition 65 was adopted by California voters after it appeared on the ballot in the November 1986 election. As described in the voter pamphlet, the measure required warnings before exposing any person to a chemical “known to the State of California” to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity.2 The proposition also prohibited discharging those dangerous chemicals into the drinking water supply.3 Under the new law, the Governor was ordered to designate a lead agency to produce a list of chemicals “known to the State of California” to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity.4 Although the Legislative Analyst could not provide an accurate estimate of the increased enforcement costs to state and local governments from the new measure, the Analyst expected that a portion of the increased costs would be offset by fines and civil penalties provided for in the new law.5

The proponents of Proposition 65 set out the purposes of the measure as follows:

• Keep known toxins out of the drinking water

• Require warnings to alert the public before they are exposed to the toxins

• Allow private citizens to enforce the measure in court

• Require government officials to notify the public when illegal discharges of toxic waste could pose a serious risk to public health.6

According to the proponents, all of this comes at a “negligible” cost because that cost would be offset by fines and civil penalties. The civil penalties were to be won in lawsuits brought by both public prosecutors and private citizens.7 The measure provided for civil penalties of up to $2,500 per day for each violation.8 Not all of the civil penalty went to the state treasury, however. To encourage suits by private citizens, a bounty reward was offered. One-quarter of the civil penalty that would ordinarily go to the public treasury was to be paid instead to the individual or organization that brought the suit.9 This payment, in addition to other laws providing for payment of attorney fees, established a profit motive for bringing litigation.

Enforcement by Bounty Hunter

While Proposition 65 may have been well-intentioned, it has been overshadowed by the controversial “bounty hunter” provisions. As all sides of the debate acknowledged, California already had significant regulations on the books governing toxic pollution, and many of those laws carried stiff criminal and civil penalties.10 Further, a number of existing environmental laws had “citizen suit” provisions, authorizing ordinary citizens and environmental organizations to bring enforcement actions on their own.11 The difference, however, lies with the near impossible task for businesses to defend themselves against private bounty hunters. Courts have noted that “bringing Proposition 65 litigation is . . . absurdly easy.”12 The bounty hunters are almost assured of getting an award of attorney fees at the end of litigation.13 By contrast, the business is almost guaranteed that it will never recover its cost of defense even if it prevails.14 In addition to the cost of the litigation (paying for the attorneys on both sides of the case), businesses face the possibility of ruinous civil penalties under the law.

In addition to authorizing citizen suits (and allowing the collection of attorney fees), the initiative diverted public monies to pay a further reward to the individuals and organizations bringing the suit to enforce the measure. Unlike attorney fees, which are at least theoretically tied to actual costs, the civil penalty does not pay for any cost incurred by the private organization. The payment is pure profit. There is no requirement under the law to show that the organization had costs in bringing the case. Nor is there any requirement to establish that the organization has been injured in any way by whatever violation of the law they are claiming. Anybody actually injured by environmental pollution already had the right to bring litigation for damages.15

These bounties are unique in the law. Civil penalties are public monies. Indeed, the initiative identified these monies as the source of revenue to pay for the costs of the new law. To give a portion of these penalties as a reward for bringing litigation, in addition to massive attorney fees, establishes a lucrative profit motive for litigation.

To be clear, these cases are not difficult for the bounty hunters to win. A business charged with exposing Californians to a chemical on the list of cancer-causing substances without warning cannot defend itself by showing a long history of safe use. In one case, for example, the business argued that there was a 150-year history of safe use with no scientific evidence of adverse health effects.16 The court ruled that under the law the century and a half of safe use is irrelevant. Instead, under Proposition 65, the business bears the burden of proving that any exposure to a chemical on the list is 1000 times below the level of no observable effect.17 Faced with such an impossible burden of proof, many companies determined that the most prudent business decision is to pay any demanded attorney fees and penalties to the bounty hunter rather than contesting the case in court. As California soon learned, this was a recipe for abusive litigation tactics by the bounty hunters.

THE LEGISLATURE ADDRESSES LITIGATION ABUSES

The bounty hunter provision of Proposition 65 offered a profit incentive for lawsuits to enforce the measure. That profit was balanced against a very low risk. Other than paying for your own attorney, the cost of bringing a Proposition 65 enforcement action was very low and the risk of being assessed attorney fees incurred by a business that successfully defended the action was negligible.18 The cost of sending out a threatening demand letter was even lower. With these demands, private groups could, and did, coerce settlements by playing on the fears of the business of a potentially ruinous civil penalty and attorney fee award.19 The authors of the demand letters could price their settlement demands at or below the cost of what it would cost the business to defend the lawsuit. As noted above, however, the business owner could not win a case by showing the product at issue was safe, or even that nobody had been injured in the history of the product’s use. To prevail against a failure-to-warn charge, the business must prove that any exposure to a listed chemical is 1000 times lower than the “no observable effect” level.20

Abuses soon followed. In one case (Consumer Defense Group v. Rental Housing Industry Members), a law firm created an “astroturf” environmental group to be a plaintiff in Proposition 65 litigation. As the court explained, the so-called environmental group consisted of partners from the law firm.21 Using this front group, the law firm sent out hundreds of demand letters charging businesses with failure to provide warnings.22 The firm would use these demand letters to, in the words of the court, “extort” payments of attorney fees or contributions to the front group.23

None of the purposes of Proposition 65 were served by these “bounty hunters.”24 The demand letters charged businesses with violating Proposition 65 because they had parking lots (thus inviting automobiles and their exhaust), swimming pools (thus using chemicals to keep the pools clean), roofs (the attorney claimed to be able to tell that the tar used on the roof was dangerous just by the smell), and gardens (fertilizers and insecticides might be used).25 The most astounding demand letters sought damages from businesses on the grounds that they had furniture and painted walls.26 The letters claimed that furniture potentially exposed customers to toxic chemicals used in paint or seat cushions.27

Only a few of these cases actually went to court, and prior to changes in the law, these demand letters were not filed with any public agencies. Therefore, there was no way to know if the abuses cited above were the norm or were simply an extreme example of one law firm seeking to maximize its profits. Nonetheless, Proposition 65 did provide a profit motive for bringing litigation and imposed no cost for bringing cases like those described above. Clearly a change in the law was needed.

Because it was enacted as an initiative measure, the California State Legislature is not entirely free to amend the law. Under California’s Constitution, initiative measures may only be amended by another initiative—unless the proposition provides a different method.28 Proposition 65 does permit legislative amendment, but imposes significant restrictions on the power of the Legislature to change the law. Any amendment must “further the purpose” of the initiative and must be approved by a two-thirds super majority vote.29

Even with this restriction, the Legislature was convinced of the need to address the abuses of the law by the bounty hunters. Thus, in 1999 the Legislature amended the measure to require the bounty hunters to file copies of their settlements with the Attorney General.30 Because of this amendment, neither the organization bringing the suit or the business defending it could hide the settlement. If a business was engaged in a practice that endangered public health, the terms of the settlement ending those practices was now available to the public. By the same token, however, private organizations could not use the threat of publicity or promise of a quick settlement in exchange for a quick, confidential payment. The payments to the bounty hunter are now also subject to public disclosure.31 These settlements are posted on the Attorney General’s website and provide an important source of information for the public today.32

These changes to the law only required disclosure, however. The amendments did nothing to address the charge that unscrupulous groups were extorting settlements from businesses on the basis of frivolous claims.

In 2001, the measure was amended again, this time to require the bounty hunters to provide a “certificate of merit” before proceeding with their action.33 This gave the Attorney General the authority to demand the underlying information behind the certificate in order to investigate the merit of the action.34 The 2001 amendments also attempted to impose some restrictions on the bounty hunters’ ability to settle cases. Under the amendments, courts are now required to make specific findings that the warnings required under the settlement comply with the law and that any imposed civil penalty meets specific standards.35 The Attorney General is given special authority to participate in settlements of bounty hunter litigation to help enforce these provisions.36

One would have expected these changes to lead to fewer questionable lawsuits and a well-supervised process for the assessment and collection of civil penalties. While the requirements for a certificate of merit have led the Attorney General to oppose some claims, the Attorney General has done little to ensure that any civil penalties assessed are related to any actual danger that Californians are subjected to an increased risk of cancer based on the failure to post a warning sign. Indeed, former California Attorney General Bill Lockyer enacted regulations that gave permission to private groups to accept a higher, private payoff in exchange for having no civil penalty assessed against the alleged violator.37 Any money that would have gone to the public treasury to help pay for enforcement of the law can now be diverted to the organizations that bring the legal challenges.

WHERE HAS THE MONEY GONE?

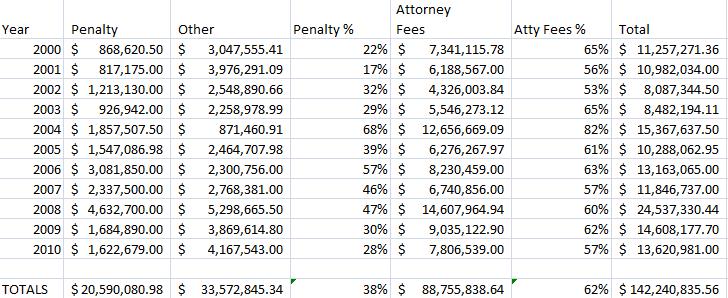

Between 2000 and 2010, more than $142 million has changed hands as a result of settlements in lawsuits brought pursuant to Proposition 65. That is just the amount of money that businesses have paid to settle cases. It does not include legal or other costs imposed on business. Nor does it include the costs of cases that actually went to trial.

As shown in the chart below, the vast majority of those payments have gone to pay the attorney fees of groups filing challenges. Nearly $90 million of the total, or 68 percent, is listed as payments for attorney fees. Civil penalties, by contrast, account for only 14 percent of the total. The remaining 24 percent—nearly a quarter of all the money collected—is listed as “other” payments—that is, payments that are made directly to the organization that brought the suit or some other organization designated by the filing organization.

Summary Chart38:

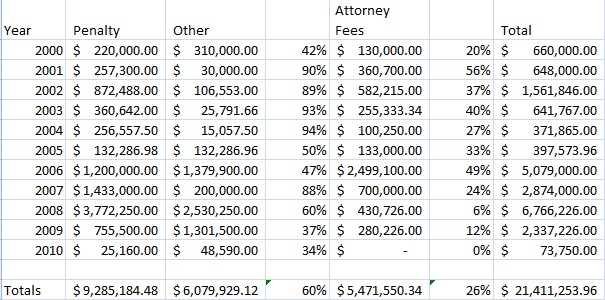

Actions brought by the Attorney General are included in these statistics and provide a good point of comparison. How do the private bounty hunters compare in terms of efficiency (the ratio of attorney fees to civil penalties) and in terms of diverting civil penalties meant for the state treasury to private organizations?

Attorney General Chart39:

During the 11-year period of 2000 to 2010, the Attorney General accounted for total collections of more than $21 million—a little less than 15 percent of the total amount of money collected from Proposition 65 litigation settlements in this time frame. Of that $21 million, only 26 percent was collected as attorney fees. Nearly half of all money collected by the Attorney General was designated as civil penalties. The remainder of the money, about $6 million, was categorized as “other,” presumably payments directed to private organizations that helped identify the problem that led to the litigation.

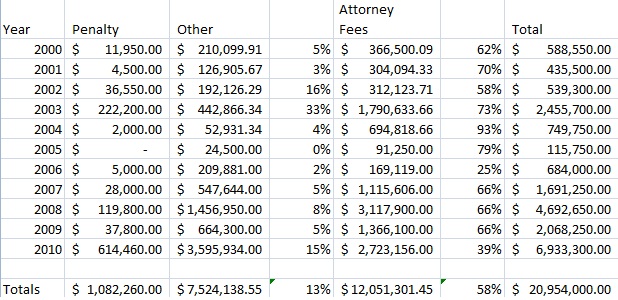

One private organization that accounted for nearly the same amount in Proposition 65 settlements as the Attorney General was the Center for Environmental Health. Between 2000 and 2010 this group accounted for nearly $21 million in payments. However, the Center for Environmental Health’s attorney fees collections were more than double those of the Attorney General. Although it collected nearly the same amount of money as the Attorney General, the Center for Environmental Health only took in a little more than 10 percent of the civil penalties collected by the Attorney General. A full 35 percent of the money collected by the Center for Environmental Health—about $7.5 million—was designated as “other” payments. Combining the categories of civil penalty and “other” should have resulted in a bounty of about $2.1 million and a civil penalty paid to the state treasury of nearly $6.4 million. Instead, the state treasury received only $1 million, and the “other” payments totaled more than $7.5 million. Nearly all of this $7.5 million went to the Center for Environmental Health.

Center for Environmental Health Chart40:

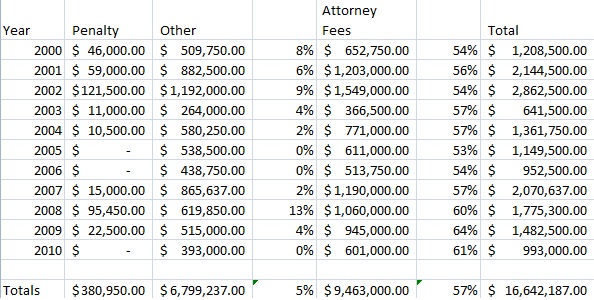

The contrast is even more stark when other groups are compared to the Attorney General. Mateel Environmental Justice Foundation collected $16.6 million in settlements from Prop 65 litigation between 2000 and 2010. Of that, 57 percent, or $9.4 million, were designated as attorney fees. Only $380,950 were designated as civil penalties, however. The remaining nearly $7 million went toward “other” payments. These “other” payments were generally directed to other organizations that performed the research necessary for future Proposition 65 litigation. As written, Proposition 65 would have allowed only $1.8 million to be diverted to these other organizations as Mateel’s “bounty” payment. The remaining $5.3 million would have been paid to the state treasury to fund the cost of the law.

Mateel Environmental Justice Foundation Chart41:

These organizations are not singled out because of the merits of their settlement demands. No analysis has been made of the types of challenges they made or the value to public health of their actions. Instead, this analysis shows the vastly increased costs due to bounty hunter enforcement when compared with enforcement actions brought by the Attorney General. The analysis also shows the massive diversion of civil penalties from the public treasury to private organizations. It bears emphasis that these diversions of civil penalty payments to private organizations were approved—and even encouraged—by the regulations put in place by former California Attorney General Lockyer. Those regulations, however, are themselves illegal.

DIVERSION OF CIVIL PENALTIES TO PRIVATE ORGANIZATIONS IS ILLEGAL

Neither Proposition 65 nor any of its legislative amendments permit reducing the civil penalty in order to make a direct payment to the organization bringing the case or some other organization. Nonetheless, former Attorney General Lockyer issued guidelines expressly stating that no objection will be lodged against proposed settlements that include such a private payment. Apparently this has become the preferred style of settlement, as civil penalties continue to shrink and the “other” category of payments has grown larger. Notwithstanding the popularity of redirecting public funds from the state treasury to private organizations without involvement of the Legislature, these “payments in lieu of civil penalty” settlements are illegal. Redirecting public funds to private purposes is contrary to the language of the measure, and it is doubtful that even the Legislature would have the authority to amend Proposition 65 to authorize such payments.

As already noted, the Legislature does not have a free hand to amend initiative measures. Proposition 65 specified that any amendments must be approved by a super-majority vote of the Legislature and must promote the purposes of the measure. The ballot arguments sent to California voters emphasized that one of the purposes of Proposition 65 was for the measure to pay for itself. Civil penalties that would be collected under the law would be used to offset the cost of enforcement and would be available for other environmental enforcement purposes.42 As shown above, however, collection of civil penalties has dwindled to a small percentage of the total settlements collected. The money intended to pay for public enforcement and other public purposes has been diverted to private organizations.

The idea that private litigants might be able to bargain away payments to the state treasury in favor of payments directly to themselves appears nowhere in Proposition 65. In fact, any such action is in stark contrast to what voters originally enacted. Proposition 65 states that any person who violates its provisions “shall be liable for a civil penalty not to exceed $2,500 per day for each such violation in addition to any other penalty established by law.” Section 5 of the initiative apportioned the civil penalty between various funds and noted that 25 percent of the penalty was to be paid to a private individual that brought the action. The measure thus sets clear limits on the financial liability of businesses violating the law (civil penalties of up to $2,500 per day in addition to other legally-established penalties) and sets a clear limit on how much the organization bringing the action can receive (25 percent of the penalty). There is no room in this language to permit a system of allowing environmental organizations to bargain with an alleged violator for the imposition of a lower penalty in exchange for direct payment to the environmental organization.

As noted earlier, the Legislature may only make changes that further the purposes of the initiative, and then can only do so by a two-thirds super-majority vote.43 Any change to allow private organizations to determine, on their own, whether to keep some or all of the civil penalty for themselves is not such a change furthering the initiative’s purpose. One of the purposes of the act was to lessen the fiscal impact on state and local government through the assessment of fines and penalties. This point was mentioned in both the Legislative Analyst’s and the Attorney General’s analysis of the measure. That purpose cannot be met if a non-governmental entity has the discretion to divert civil penalties to their own private purposes. The trend toward substituting direct payments to non-governmental entities instead of civil penalty payments to the state treasury violates the provisions of Proposition 65. The Legislature has never authorized this diversion of public funds, and it has no power to do so.

Former Attorney General Lockyer’s regulations authorizing diversion of public funds to private organizations do not purport to be binding legal requirements. Instead, the regulations are characterized as “guidelines” for private litigants and courts. In point of fact, however, these regulations serve as a “green light” for private organizations who wish to divert civil penalties from the public treasury to private uses. They are an announced policy that the Attorney General will not enforce the law. Attorney General Lockyer did not have the authority to issue such regulations because he only has authority as delegated by the initiative. Any regulation in excess of that authority is void.44

The Attorney General has the legal duty under Proposition 65 to police the legal actions brought by bounty hunters, and to oppose in court those proposed settlements that violate the law. Far from having authority to authorize diversion of civil penalties to private organizations, the Attorney General has the legal duty to oppose any settlements with such a provision.

Even in the absence of an objection from the Attorney General, the courts also have a duty to reject settlements that do not comply with the terms of the initiative. Judicial approval of settlements is only available for those agreements that comply with the law. Settlements that divert civil penalties to private organizations cannot meet that simple test.

Even if these settlements do not comply with the terms of the initiative, the Attorney General has said that they are an appropriate form of “cy pres” relief. But such use of the cy pres doctrine is improper. Cy pres is a legal doctrine whose purpose is to prevent the failure of a charitable trust. Sometimes after a charitable trust has been created, the activity that trust was formed to fund becomes impossible.45 For example, if a trust was established to pay for the upkeep of a park, that purpose becomes impossible to fulfill if the park is converted to a different use. Instead of allowing the trust to fail, the courts have ruled that the money should instead be devoted to a charitable purpose as close as possible to the original purpose of the trust. This alteration of the trust preserves the donor’s charitable intent and allows the funds that were set aside to continue to fund charitable activities.

In modern times, the cy pres doctrine has also been applied to damage awards collected in class action litigation that cannot be paid to members of the class. This happens most often when it is impossible to identify all of the injured parties or the amount of recovery for each class member is too small for individual payments to be practical.46 Instead of allowing the money to go back to the wrongdoer, the courts have used a version of the cy pres doctrine to allow the damages award to be paid to private organizations whose activities will, in some manner, provide a benefit to members of the class. Both the original charitable trust and the modern class action version of the cy pres doctrine share one critical feature—the payments are diverted to a new purpose because something has happened to make it impossible to use the money for the originally-designated purpose.

In the case of Proposition 65 settlements, however, it is not at all impossible to pay the civil penalties to the California State Treasury. The State of California is more than willing to accept any and all payments to the treasury—especially payments that are meant to offset the cost of a regulatory program to protect the health and safety of California residents.

No matter how the question is analyzed, the answer is the same. Diversion of civil penalties to private organizations is not authorized by Proposition 65. The Attorney General has a legal duty to oppose any settlements that include such a diversion. Courts have a legal duty to reject any such settlements whether or not the Attorney General has filed an opposition.

THE BOUNTY HUNTER VERSUS THE PUBLIC INTEREST

It is no surprise that there have been abuses by bounty hunters under Proposition 65. Threats of litigation have been served without adequate justification. Civil penalties intended to help with the cost of the law have been diverted to private organizations. The law encourages that behavior, however, by offering a cash reward with little or no countervailing risk of loss. Individuals and organizations have every incentive to threaten and file litigation. Even with meritorious litigation, environmental organizations have the incentive to trade civil penalties that would be paid to the state treasury for payments to themselves or allied organizations that will be used to set up the next case.

There is a reason that bounty hunter provisions are so rare in the law. In California, the Attorney General is the top law enforcement official and the only one with the constitutional duty to enforce laws like Proposition 65. When the Attorney General brings an enforcement action, it is brought in the name of the “people of the State of California” indicating that it is an “exercise of the sovereign power” of the California. Such cases are not brought lightly. The Attorney General is expected to exercise sound judgment in choosing cases to prosecute in order to focus on the most serious violations and those cases where the public health and safety is truly at risk. The public interest, not profit, is the motivation for public enforcement actions. While individual public officials may make bad or even illegal decisions, there is a public expectation that officials will act, by and large, for the good of the public rather than for their own private profit.

This is the reason that government officials generally cannot be sued for failure to enforce a particular law in a particular situation. As the United States Supreme Court has noted:

This Court has recognized on several occasions over many years that an agency’s decision not to prosecute or enforce, whether through civil or criminal process, is a decision generally committed to an agency’s absolute discretion. See United States v. Batchelder, 442 U. S. 114, 123-124 (1979); United States v. Nixon, 418 U. S. 683, 693 (1974); Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U. S. 171, 182 (1967); Confiscation Cases, 7 Wall. 454 (1869). This recognition of the existence of discretion is attributable in no small part to the general unsuitability for judicial review of agency decisions to refuse enforcement.

The reasons for this general unsuitability are many. First, an agency decision not to enforce often involves a complicated balancing of a number of factors which are peculiarly within its expertise. Thus, the agency must not only assess whether a violation has occurred, but whether agency resources are best spent on this violation or another, whether the agency is likely to succeed if it acts, whether the particular enforcement action requested best fits the agency’s overall policies, and, indeed, whether the agency has enough resources to undertake the action at all. An agency generally cannot act against each technical violation of the statute it is charged with enforcing.47

These same considerations have convinced the Supreme Court to outlaw criminal prosecutions by attorneys with a financial interest in the case. The Attorney General or the District Attorney is not the attorney

of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done. As such, he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape nor innocence suffer.48

It is the job of the public prosecutor to seek justice—not a private bounty payment.49

When the decision to prosecute is handed over to the bounty hunter, however, there is no consideration of what is in the public interest or what priorities should be pursued. There is no “complicated balancing of a number of factors which are peculiarly within [the] expertise” of government regulators. Instead, “enforcement” actions are open to those motivated by private profit rather than the public interest. These are critical considerations because businesses are likely to settle cases even if there is no clear liability or violation of law. It is far better to settle an action for a payment of a certain sum to the organization bringing the suit than to risk financial ruin of costly litigation. It may even be that the cost of the settlement will be less than the cost of hiring attorneys to defend the case.

Finally, the bounty hunter does not play by the same rules as government officials like public prosecutors. The District Attorney and the Attorney General have a duty to represent the public interest and are, at least in theory, answerable to the voters for their behavior. The bounty hunter is under no such duty. The bounty hunter is motivated by its own private concerns, which may or may not be similar to the public interest. In the main, however, the bounty hunter operates in pursuit of the bounty. This can lead to actions inimical to the public interest, such as unwarranted claims (as documented by the court in Consumer Defense Group v. Rental Housing Industry Members50) and diversion of civil penalties from the state treasury to private organizations.

These considerations make it especially important that the Attorney General take a proactive stance to ensure proper enforcement and implementation of Proposition 65.

CONCLUSION

Enforcement by bounty hunters is subject to abuse—especially when the chief law enforcement officer of the state authorizes those bounty hunters to divert resources intended for the State Treasury to private organizations. The Legislature has recognized this flaw in Proposition 65 and has attempted to address those abuses. In 2001, the Legislature acted to address “abusive actions brought by private persons with little or no supporting evidence.” The 2001 amendments required bounty hunters to file a certificate of merit with the Attorney General attesting that they had consulted appropriate experts before filing their claims. The amendments also set out specific guidelines for determining an appropriate civil penalty. In approving any civil penalty, the court must consider the extent of the violation, its severity, the impact of the penalty on the violator, the good-faith actions taken by the violator, whether the violation was willful, what deterrent effect the penalty will have on other members of the regulated community, and other factors that justice may require. A central purpose of these amendments was to place the public interest in control of setting the amount of the penalty—not the profit motive of the bounty hunter.

The 2001 amendments also established an increased role for the Attorney General. Under the amendments, any proposed settlements must be served on the Attorney General so that a public officer serving the public interest can ensure that the purposes of Proposition 65 are being met. The law now authorizes the Attorney General to participate in any settlement to ensure that the civil penalty meets the legislative guidelines and that any proposed attorney fee award is not excessive.

The tools are in place for the Attorney General to reform Proposition 65 litigation in California. A first step could be for the Attorney General to repeal the regulatory guidance permitting civil penalties to be diverted from the public treasury to a private organization. As outlined above, this diversion of public moneys to private organizations violates Proposition 65. There are enough problems with the bounty hunter provision of the original measure. There is no need to increase the potential profit to the bounty hunter by the illegal diversion of public funds.

A second step would be for the Attorney General to actively oppose any proposed settlements that include a diversion of the civil penalty toward private organizations. Money designated by law for the state treasury should be paid to the state treasury for appropriation by the State Legislature.

Third, the Attorney General could reduce misuse of the bounty hunter provision by scrutinizing proposed settlements to determine whether the civil penalty meets the guidelines set out in the law. Low penalties that are traded for higher attorney fees violate the law, but so do high penalties traded for a quick settlement. The Attorney General must be active in this arena to ensure that the litigation and the penalty serve the public, not the profit motive of the bounty hunter and its attorneys.

Finally, the courts are bound to give closer scrutiny to proposed settlements. Court approval is already required for all settlements under the law.51 To be effective, however, these provisions require parties to justify the complaint and the settlement award. Special vigilance against the diversion of civil penalties to private organizations is warranted. But local superior courts need the assistance and leadership of California’s top law enforcement official. The worst abuses of the bounty hunter provision can be controlled only with active oversight by the Attorney General and strict supervision of settlements by the courts.

* Associate Clinical Professor of Law, Chapman University School of Law

Endnotes

1 The term “bounty hunter” is technically incorrect. A true bounty hunter only pursues targets selected by law enforcement or judicial officers. As noted below, this law allows private citizens to select the targets of prosecution and gives a financial incentive for that incentive. There is no public oversight in the selection of businesses targeted for litigation.

2 State of California, Ballot Pamphlet, General Election, Nov. 4, 1986, at 52.

3 Id.

4 Id. at 53 (proposed Health & Safety Code §25249.8).

5 Id. at 52 (“A portion of these costs could be offset by increased civil penalties and fines collected under the measure.”).

6 Id. at 54.

7 Id. at 52, 54.

8 Id. at 53 (proposed Health & Safety Code §25249.7).

9 Id. at 63 (proposed amendments to Health & Safety Code §25192).

10 Id. at 54.

11 E.g., Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. §1365; Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. §7604. In California, citizens and taxpayers generally have the right to bring actions to force public agencies to enforce environmental statutes. See Cal. Code Civ. Proc. §1085.

12 Consumer Def. Group v. Rental Hous. Indus. Members, 137 Cal. App. 4th 1185, 1217 (2006).

13 See id. at 1220 (noting appropriate award of fees in one case in spite of 150-year history of safe use of the product).

14 DiPirro v. Bondo Corp., 153 Cal. App. 4th 150, 199 (2007) (defending business is not entitled to fees because it is defending its own personal interest rather than the public interest).

15 See Orange County Water Dist. v. Arnold Eng’g Co., 196 Cal. App. 4th 1110, 1126 (2011).

16 Consumer Cause v. SmileCare, 91 Cal. App. 4th 454, 466 (2001).

17 Id. at 467.

18 See Consumer Def. Group, 137 Cal. App. 4th at 1217; DiPirro, 153 Cal. App. 4th at 199.

19 See Consumer Def. Group, 137 Cal. App. 4th at 1216 & n.22.

20 Consumer Cause, 91 Cal. App. 4th at 467

21 Consumer Def. Group, 137 Cal. App. 4th at 1190.

22 Id.

23 Id. at 1210.

24 In oral argument before the court, the attorney proudly proclaimed that he was, indeed, a “bounty hunter.” Id. at 1189 n.1.

25 Id. at 1189.

26 Id. at 1194.

27 Id.

28 Cal. Const. art. II, §10.

29 Proposition 65, §7.

30 1999 Cal. Stats., ch. 599.

31 Id.

32 See Proposition 65 Enforcement Reporting, http://ag.ca.gov/prop65/index.php (last visited Feb. 27, 2012).

33 2001 Cal. Stats., ch. 578.

34 Id.

35 Id.

36 Id.

37 11 Cal. Code of Regs. §3203

38 See Proposition 65 Enforcement Reporting, http://ag.ca.gov/prop65/index.php (last visited Feb. 27, 2012).

39 See id.

40 See id.

41 See id.

42 Ballot Pamphlet at 52.

43 Proposition 65, §7; see People v. Kelly, 47 Cal. 4th 1008, 1025 (2010).

44 Cal. Gov’t Code §11342.2; Morris v. Williams, 67 Cal. 2d 733, 748 (1967).

45 Cundiff v. Verizon Cal., Inc., 167 Cal. App. 4th 718, 729 (2008).

46 Id.

47 Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. 821, 831-32 (1985).

48 Young v. U.S. ex rel. Vuitton et Fils S.A., 481 U.S. 787, 802-805 (1987) (quoting Berger v. United States, 295 U.S. 78, 88 (1935)).

49 Young, 481 U.S. at 804 (citing Model Code of Prof’l Responsibility EC 7-13 (1982)).

50 137 Cal. App. 4th 1185, 1217 (2006).

51 Cal. Health & Safety Code §25249(f)(4).