Volume 13: Issue 1

A Retrospective on the 1921 Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Establishing a strong system of constitutionalism is crucial for the development of modern statehood and the democratic institutions of Georgia. An indispensable prerequisite for this end is the existence of a constitution that ensures the principles of democratic governance, human rights, and rule of law. The Constitution of Georgia, adopted on August 24, 1995, is an endeavor in this direction. At the same time, we must analyze those political and legal traditions and documents, which, along with the modern global experience in constitutionalism, laid the ground for the present supreme law of Georgia and its future development.

In this respect, the Constitution of February 21, 1921, ninety years old, is of utmost importance. Soon after its adoption, Georgia was occupied by Russia and the Constitution was suspended. Correspondingly, during Soviet rule, analysis and evaluation of the Constitution were taboo, and only minor works on this theme by foreign and Georgian authors working abroad have been preserved. Having this in mind, I deemed it pertinent to recall the Constitution of 1921 and make a brief analysis and evaluation for interested readers.

It is not coincidental that the 1995 Constitution now in force states in the preamble that it is based on the historical and legal bequest of the 1921 Constitution, thus acknowledging the political and legal hereditary link between modern Georgia and the then-independent Republic of Georgia. The 1921 Constitution symbolizes aspirations of Georgia during that time toward the formation of a unified, democratic, and independent state. Despite the fact that the country did not have an independent legal and constitutional atmosphere and had languished for more than a century under the Russian empire, authors of the 1921 Constitution managed to create a legal document that stood out among the post-World War I constitutions in its uniqueness and vision.

A parliamentary governance system, the establishment of local self governance, the abolition of the death penalty, freedom of speech and belief, universal suffrage (pressing at that time for an equal right to vote for men and women), the introduction of jury trials and guarantee of habeas corpus, as well as many other provisions, were some of the features of the 1921 Constitution that distinguished it among the constitutions of that time, and among the modern European ones too, for its progressiveness.

This document, adopted by the Georgian legislators in 1921, can unquestionably be considered one of the most advanced and perfect supreme legislative acts oriented toward human rights in the world for its time—i.e. the beginning of the 20th century. It reflects the most advanced legal and political discourse and tendencies underway in the Western European countries or the U.S. at that time. In the words of Hans-Dietrich Genscher, the former Federal Foreign Affairs Minister of Germany: “At that time it [the 1921 Georgian Constitution] already advocated such values as liberty, democracy and rule of law, which the modern Europe is based on currently.”1

Ramsey McDonald, a prominent British politician, later twice Prime Minister of Great Britain, while speaking about the achievements of Democratic Republic of Georgia in the letter published in the magazine “Nation” on October 16, 1920 after his visit, stated: “I familiarized myself with its constitution, its social and economic reconstruction[,] and what I saw there, I wish I could see in my country too.”2

BACKGROUND

Legal culture in Georgia was being formed from the very early stages of its history. The legal works elaborated in ancient times provided for the important issues of civil, family, and criminal law, as well as state structure.

The most ancient compilation of laws that has come down to us is Bagrat Kurapalat’s The Book of Law, which dates back to the 11th century.

Important Georgian legal works were created in the 13th and 14th centuries. Written during the reign of King George V, The Brilliant, “The Order of the King’s Court” is the most noteworthy of all the legal works of the era. This unique book is also called the unified feudal Georgia’s Constitution.3

Another legal work of importance is “Dasturlamali.” Its creation laid a solid basis for elaboration of the state law.4 Old Georgian legal books were published as a single compilation by the order of Vakhtang the 6th, and he drafted this particular work in 1705-07. Dasturlamali reflects the aspiration to develop law5 and aimed at regulation of the state governance characteristics of a feudal system.6

It is noteworthy that during the 19th and 20th centuries, when the adoption of a constitution was considered, political points of view of Georgian lawyers and politicians were greatly influenced by Georgian public figures and statesmen, like Solomon Dodashvili, Ilia Chavchavadze, Niko Nikoladze, Mikhako Tsereteli, Archil Djordjadze, and others, who were acquainted with the advanced political-philosophical thinking of not only the Russian empire of that period, but also of Western Europe and Northern America.7 As they were advocates of modernization, democratization, and self-determination, they called on Georgia to embark on the road toward Europe and the U.S.8

A Short History of THE ELABORATION AND ADOPTION of the Constitution

The period during which the first Republic of Georgia and later the 1921 Constitution were being formed coincided with a crucial time in world history. The major European empires—Austro-Hungarian, Russian, Ottoman, and others—were breaking up, and smaller nation states were taking their place. In the chaos caused by the First World War, the ultra-left and right political forces jeopardized democratic values. The economic crisis brought about by the results of World War I rendered the socialist ideas rather popular in much of the world, and this, in its turn, led to the formation of communist and later totalitarian-fascist regimes in Europe. They came to power in some countries using socialist-populist slogans.

The successful national emancipatory movement that brought an end to the almost century-long annexation of Georgia, and led to the formation of the first Republic, were to a great extent facilitated by external factors, including the political and military cataclysms underway in Russia. Following the 1917 February Russian revolution, a convention (the so-called “National Council”) of political parties of Georgia (excluding Bolsheviks, who boycotted the Council) and representatives of public organizations was held, and it was chaired by Noe Zhordania.

By the time of the establishment of the National Council, the whole Georgian political spectrum (except for Bolsheviks, who did not exert serious influence upon society) had embraced the idea of independence, without serious contradiction.9

It was the above-mentioned National Council that on May 26, 191810 declared the independence of Georgia.11 The act, which founded an independent Georgian State, declared that “the political form of governance of independent Georgia is a democratic republic.” The final article of the act stated that, before convoking the Constituent Assembly, “the rule of the whole of Georgia was assumed by the National Council . . . .,” which was later called the Parliament of Georgia. The government of the newly-created democratic republic had actively begun democratic reforms, reconstruction of the country from scratch, as well as the creation of different institutions.12

In 1919, the Constituent Assembly (Parliament) was elected by exercising the most democratic suffrage in that period. It was marked by equal suffrage, women’s participation in the elections, and other democratic elements. A governance model that ensured efficient control of the Parliament over the government was put into practice. The Parliament adopted more than 100 laws regulating different spheres. Some of the measures included recognizing private property, creating a positive environment for foreign investors, introducing agrarian reform, mandating judicial reform, putting in place jury trials, and providing for the election of lower judges by the local governments.

Despite unfavorable external factors, Georgia managed to gain recognition in the international arena. In 1920, it was de facto recognized by the major Western countries,13 and in January 1921, the same countries and the League of Nations recognized it de jure.14

The social democrats represented an absolute majority in the National Council (as in the Constituent Assembly, they were elected by direct vote). Therefore, naturally, the government had also been composed of social democrats, and thus the Georgian government of 1918-1921 can be considered the first social-democratic-orientated government in Europe and, in fact, the world.15

The primary objective of the government of that time was to create an exemplary democratic state in the Southern Caucasus. Karl Kautsky, a prominent European politician, when speaking about the successful political, legal, and economic reforms launched by Georgian social-democrats, noted that the Georgian democratic road of 1918-1920 had fundamentally differed from the Bolshevik path, which consisted of dictatorship and tyranny.16 Creation of an exemplary democracy in the Southern Caucasus should have been, to a certain extent, an antidote and even an effective alternative to the Bolshevik tyranny in Russia. But in hindsight, Kautsky’s impression seems a little idealistic, as later, the Bolshevik aggression against Georgia could not be stopped solely by democratic values.

The crowning achievement of the entire process was the adoption of the 1921 Constitution. During the three years before the occupation by Soviet Russia, Georgia acted speedily to adopt democratic reforms and commence work on a new draft Constitution based on democratic principles. The goals of the new Constitution were to streamline the internal legal and political system as well as represent Georgia in the international arena as the most democratic country not only in the region, but in all of Europe. This factor was important as the country embarked on the road to restoration of its historical independence.

The “National Council of Georgia” began the elaboration of the 1921 Constitution through the activity of the Constitutional Commission created in June 1918. The Commission consisted of members of different political parties. Election of the Constituent Assembly by direct vote and universal suffrage was marked by the participation of women and the absence of a property census and was held on February 14-16, 1919. The Georgian social-democratic party earned the vast majority of parliamentary seats (109 seats out of 130). The remaining seats went to national-democrats, social-federalists and Essers (social-revolutionaries). Bolsheviks earned very few votes and did not receive a single seat.17

The newly-elected Constituent Assembly set up a Constitutional Commission consisting of fifteen members, the majority of whom were social democrats.

The authors of the Constitution, who had the experience of studying and working in Europe, naturally knew the texts of contemporary world constitutions, their underlying principles, and associated work. Experience gleaned from these constitutions significantly influenced the Georgian legislators. Common approaches on different issues are clear when compared to the Swiss Constitution of 1874, Belgian Constitution of 1831, United States Constitution of 1789, German Constitution of 1919, Czechoslovakian Constitution of 1920, and French Constitution of 1875. Almost all existing constitutions had been translated into Georgian and published in the press between 1919-1920, and concurrently in various issues of the newspaper Ertoba. Members of the Constitutional Commission and other lawyers had also published articles and reviews on the essence of different constitutions.

The process of working on the new draft Constitution had taken the newly-created commission considerable time as it endeavored to study as much international experience as possible, and also reach a political consensus on important issues. In July 1920, the draft Constitution was published for review. And in November 1920, the Parliament started the procedure of its review and adoption.

At the same time, Russia tried to hamper Georgia’s aspirations to become an independent state. In February 1921, Soviet Russia occupied and subsequently annexed the country. The Russian army offensive prioritized the adoption of the draft Constitution, with certain amendments on February 21, 1921. By this time, almost all chapters of the Constitution had been reviewed and adopted by the Parliament, and the article-by-article review process had already started. Given the existing situation, it became necessary to speedily adopt a full-fledged Constitution that represented a sovereign country before the world and the enemy. On February 25, 1921, the 11th Army of Soviet Russia occupied Tbilisi and declared Soviet power in Georgia. The government of independent Georgia was forced to move to Western Georgia—the Black Sea town of Batumi. It was in this town that the official text of the 1921 Constitution of Georgian Republic was first published.

The Structure and Legal Nature of the 1921 Constitution

The landmark 1921 Georgian Constitution consisted of 17 chapters and 149 articles.

Based on the fact that, practically speaking, the 1921 Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia was never implemented, it is hard to say whether or not it would have worked. Nevertheless, article-by-article study and research of its contents gives us an opportunity to draw interesting conclusions. The importance of these conclusions is not defined solely by historical and legal points of view, as the basic principles recognized by the norms of the 1921 Constitution and the majority of relationships regulated by it are also relevant to modern constitutional law. It is also possible to draw many political-legal parallels between the 1921 and present Constitutions and between the stages of development of Georgia now and then.

It must be mentioned that the 1921 Constitution belongs to the first wave of constitutions drafted as a result of the historical evolution of justice. The date of its adoption coincides with the end of World War I and the emergence of new states in place of empires like the Russian, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian Empires. The countries that adopted new Constitutions at that time include Austria, Germany (the Weimar Republic), Czechoslovakia, Finland, and the Baltic Republics.

The Basic Human Rights Stipulated by the 1921 Constitution

The constitutional provisions reflecting human and citizens’ rights can be considered the greatest achievement and the prominent symbol of progressiveness of the 1921 Constitution of the Georgian Democratic Republic. The authors of the 1921 Constitution tried to establish a system under which these rights were based on the traditional principle of individual liberty.

Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution provide a liberal approach to human rights for that period, defining the principle of habeas corpus. Unlike in other democratic countries during that time, the provisions provided for expedited court hearings for those arrested for alleged crimes. An arrested person had to be brought before a court within twenty-four hours of arrest, but, as an exception, this term could be extended for twenty-four hours more if the court was too far away and it took more time to bring a suspect before it (forty-eight hours in total). A court was also given twenty-four hours to either remand an arrested person to prison or release him immediately. The present Constitution provides for similar terms.

It is noteworthy that the 1921 Constitution abolished the death penalty.

Like other democratic constitutions of that period, the 1921 Constitution upheld the freedom of belief and conscience (Article 31). The Constitution separated church from state. The political rights of citizens were also widely covered in the Constitution in such provisions as those recognizing the freedom of speech and printed media (Article 32), the abolition of censorship, and the freedom of assembly (Article 33). Chapter 3 also guaranteed the freedom of trade unions (Article 36) and the right of laborers to strike (Article 38). The Constitution separately provided for the rights to individual and collective petitions (Article 37).

Article 45 stipulated that “the guaranties listed in the constitution do not deny other guarantees and rights which are not listed here, but are taken for granted due to the principles recognised in the constitution.” Article 39 of the present Constitution of Georgia contains a provision with similar content. This once again underscores the inherent link that exists between the main principles of the 1921 Constitution and the present Constitution of Georgia. This provision is also similar to the Ninth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and origins of its inclusion presumably stem from that document.

The 1921 Constitution is one of the first documents in the world to reflect citizens’ socio-economic rights, which is not surprising given that social democrats were heading the government. At the same time, Georgian legislators naturally were aware of how the communist rulers in Russia had been lavishly distributing populist, social promises, and it was probably not desirable to “lag behind” the Bolsheviks in that respect.

Governance System

We can group the governance system defined by the first Constitution of Georgia with the European-type parliamentary systems popular by that time, albeit with many peculiarities.

The Constitution did not achieve a balance among the three branches of power, as its structure did not incorporate sufficient mechanisms through which the government could check the Parliament or vice versa. Some peculiarities of this governance system that distinguished it from other parliamentary systems of that time were the non-existence of a neutral institution (from the executive or legislative branches) like President (or Monarch, in the case of a constitutional monarchy), establishment of only the individual responsibility of the government, meaning that only individual ministers of the government, not the entire government as a collective body, could be replaced or dismissed by a vote of Parliament; and the government’s inability to dissolve Parliament in case of crisis.

The authors of the Constitution attempted to merge the Swiss type of direct popular democracy with the elements of a representational parliamentary system.18 Pursuance of popular sovereignty principles in the Constitution was fashionable at that time and was probably influenced by Rousseau’s ideas and the Swiss democratic experience. More precisely, in accordance with Article 52 of the Constitution, the principle of popular sovereignty was laid down: “Sovereignty belongs to the whole nation.”

Constitutional Review

The notion of constitutional review is to a certain extent provided in Articles 8 and 9. It underscores the principle of constitutional supremacy: “No law, decree, order or ordinance which contradicts the provisions and the purport of the Constitution can be issued.” The above-mentioned provisions unequivocally show the necessity of establishing consistency between the Constitution, the legal acts existing before adoption of the Constitution, and the legal acts issued after its adoption, which would have been impossible without exercising constitutional review. But the 1921 Constitution did not provide for a body of constitutional review, similar to a constitutional court in the classical understanding of this institution and its regulatory functions and authority, as was done in Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1920. It must be noted that the government, as it turns out, had already exercised some constitutional review leverage. Under sub-paragraph “B” of Article 72, one of the authorities of the government was “scrutiny and enforcement of the Constitution and laws,” although it is logical that such a function must be under the competence of a court. It is interesting that only the court had the right to repeal the acts of local governments (central bodies had only enjoyed the right to suspend these acts and appeal to the court by submitting the request for repeal of these acts). Hence, we can conclude that, though in such a case full constitutional review was not exercised, full court scrutiny of the legitimacy of legal acts was carried out, which manifested itself in courts examining the relevance of legal acts issued by local government bodies.

This is also corroborated by the function of the Supreme Court, the Senate, stipulated in Article 77, which is obliged to “scrutinise how the law is abided by.” This provision, adopted on July 29, 1919, gave the Senate the authority to examine the legitimacy of acts of all of the governmental institutions, high-ranking officials, and local governmental bodies, and, in case of aberrations from the law, the Senate was required to either suspend or repeal them. Another function of the Senate was the resolution of disputes between the state bodies concerning their competencies.

Because the Constitution abounded in ideas and principles necessary for administering constitutional review, we can conclude that establishment of such a separate constitutional body in the future or granting the function of constitutional review to general courts would have been logical had the independent Georgia not ceased to function.

Such a concept was not alien to Georgian legislators. Giorgi Gvazava, a national democrat and one of the members of the Constitution Elaboration Commission, noted:

There is only one case, when a citizen has a right not to abide by law. Such a case is called disputing constitutionality of the law. A citizen has a right to lodge a claim with a court on the constitutionality of the law which restricts his liberties or threatens him with such a restriction. The court is obliged to review this case and if it deems that the plaintiff’s claim is well grounded, it can reject the law and not guide itself by it in deciding the case.19

Gvazava, who was well-aware of the constitutional review mechanisms of Western Europe and the United States, also noted: “The court is obliged to defend the Constitution, as the main law, and reject all new laws which contradict it. Such right of review is enjoyed by the court in the USA . . . .”20

Popularity of the concept of constitutional review in political and legal circles of Georgia of that time is emphasized by the views of K. Mikeladze, one of the famous public figures and attorneys in Georgia in that period. He expressed these views in his work on the process of the elaboration of the Constitution. Drawing mostly on the United States’ experience, he maintained that the role of a court must be more than just hearing cases: they must also “review[] laws elaborated by legislative bodies in terms of their compatibility with the Constitution.”21

Occupation and Annexation of Georgia and Suspension of the Constitution

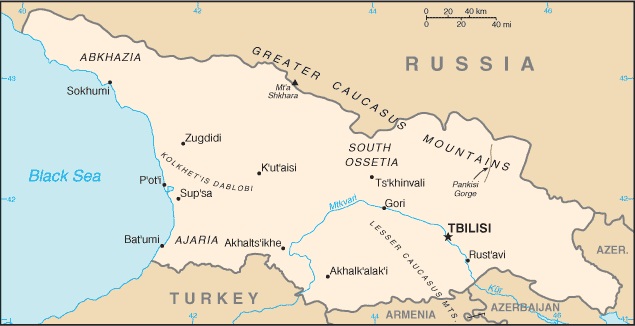

In 1918-1920, Russia had attempted a number of times, directly or indirectly,22 to trigger internal chaos on social grounds, and to foment ethnic strife in Abkhazia and Tskhinvali and other regions of Georgia. Due to the failure of these attempts and the complicated internal and external situation in Russia, it was forced to temporarily conceal its intentions. On May 7, 1920, Russia signed an agreement with Georgia and recognized its independence and territorial integity.

However, Soviet Russia managed to occupy and “Sovietize” Azerbaijan (April 1920) and Armenia (November 1920). It became evident that despite the signed agreement, soon it would attack the Democratic Republic of Georgia, too. The Georgian government still hoped that Russia would not breach the 1920 agreement and become discredited before the international community. However, the events took a different turn. In December 1920, at a meeting of the League of Nations in Geneva, Georgia was denied membership in the League (in the required two-thirds vote for admittance, ten members voted in support of Georgia, thirteen voted against Georgia, and seventeen abstained).23 Later, in January, the League and the leading states of the West recognized Georgia’s independence de jure.

After strengthening its positions inside the country and facing no sharp resistance in the international arena, despite the international recognition of Georgia, Russia violated the treaty and, with the pretext of supporting the rallying workers whom they had instigated in the district of Lore, invaded Georgia from the Armenian side in February 1921.24 On February 25, the government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia was forced to leave Tbilisi and move to the city of Batumi. Defeated by Bolshevik Russia, the last meeting of the Constituent Assembly of the independent Republic of Georgia was held on March 17, 1921, and the Assembly passed a decree temporarily suspending the operation of the Georgian Constitution.

The Georgian government in exile (mainly in France) tried by means of internal resistance and support of the Western countries to stop Bolshevik Russia’s occupation and annexation of Georgia. Noe Zhordania, addressing the international community via the British newspaper The Times (commenting on the invitation of Bolshevik Russia to the international conference in Genoa in April-May of 1922), noted: “Unless Europe voices its concern about the flagrant injustice, with which the government of Soviet Russia treats Georgia, each major country will consider this as a consent to attack neighbour countries and occupy their territories.”25 But the international situation of that period did not allow for fending off Russian aggression. Major Western countries and the League of Nations had only been expressing their “concern and worry” about Russia’s actions.26 In 1924, the rallies against the Communist regime were quashed by military force.

Further Development of Constitutionalism

From that time on, the “Sovietized” Republic of Georgia “adopted” four Constitutions (1922, 1927, 1937, and 1978), based on the principles of the Communist party. In doing so, the Soviets legitimized the existence of a one-party communist system, which had nothing in common with the principles of constitutionalism associated with democratic governance. All of them had essentially been copies of their respective preceding USSR constitutions.

In 1990, after holding multi-party elections that ushered in the national-emancipatory political parties, Georgia declared independence from the USSR. The newly-elected multi-party Parliament made important amendments to the 1978 Constitution and expunged the provisions defining existence of the Soviet-type one-party system and other anti-democratic provisions.

The Parliament elected in 1992 set up a special commission for preparing the concept of and drafting a new Constitution on February 16, 1993.27 Eventually, the commission drafted a wholly new draft Constitution, as revision of the 1921 Constitution would have been very difficult seventy years after its inception, considering the new political-legal reality.28

On August 24, 1995, the Georgian Parliament adopted the present Constitution, the preamble of which reads that it is based on “many centuries old traditions of the statehood of Georgian nation and historical legacy of the 1921 Georgian constitution.”29

Thus, despite many vital differences between the present and the 1921 Constitutions, they have the same legacy, which had been forcefully interrupted for some seventy years by Soviet Russia.

The 1995 Constitution, by taking into account modern conditions and international experience, has defined fundamental principles of human rights, forms of governance, organization of state, and other crucial issues for the country.

Conclusion

The 1921 Constitution was unprecedented. As the supreme law of an independent democratic state, it established representational democracy as well as the system of democratic governance based on popular sovereignty by ensuring an independent judicial system. The provisions on human rights created the most progressive European mechanisms oriented toward protection and guarantying of human rights.

At the same time, this document reflected the democratic aspirations of the Democratic Republic of Georgia, which could have earned our country an important place in the civilized world. Though the conditions of occupation and the resulting Soviet suspension of the 1921 Constitution negated its immediate significance, it played an important role in the political and legal development of modern Georgia.

Unlike the tyranny of Bolshevik Russia, the adoption of the 1921 Constitution is a crowning achievement of the democratic and civilized traditions and methods of democratic Georgia. While trying to substantiate this choice, Noe Zhordania (Chairman of the government of the Democratic Republic in 1918-1921), who had a premonition about Bolshevik Russian occupation of Georgia, noted: “And if we do not achieve our goal and fail, one thing will be sure, and impartial history will attest to it—that we had been going in the right way and d[id] what we could.”30

* The President of the Constitutional Court of Georgia

A longer version of this article will appear in Volume 18(2) of the European Public Law Journal (2012).

Endnotes

1 Hans Dietrich Genscher, Introduction to Wolfgang Gaul, Adoption and Elaboration of the Constitution in Georgia (1993-1995), at 9 (IRIS Georgia 2002).

2 Malkhaz Matsaberidze, The Georgian Constitution of 1921: Elaboration and Adoption 171 (2008).

3 Valerian Metreveli, The History of Georgian Law 26 (2005).

4 Zaza Rukhadze, Georgian Constitutional Law 21 (1999).

5 I. Surguladze, The Sources of History of Georgian Law 131 (2002).

6 Ivane Javakhishvili, The History of Georgian Law, Book 1 (1928).

7 A. Demetrashvili & I. Kobakhidze, Constitutional Law 27 (2008).

8 Stephen Jones, Socialism in Georgian Colors 2 (2005).

9 The full support of the idea of national independence by the social democrats and N. Zhordania at that time was also pointed out by Geronti Kikodze,the politician of the nationalist sentiment and a prominent public figure. See G. Kikodze, National Energy 138-141 (1917).

10 May 26 has been celebrated as Georgia’s Independence Day since 1990.

11 Two days later Armenia and Azerbaijan also declared independence.

12 Stephen Jones, on the 90th Anniversary of the Democratic Republic of Georgia, Matiane (Aug. 30, 2009), http://matiane.wordpress.com/2009/08/30/stephen-jones-on-the-90th-anniversary-of-the-democratic-republic-of-georgia/; see also Karl Kautsky, Georgia: A Social-Democratic Peasant Republic—Impressions And Observations, Chapter IX (H.J. Stenning trans., International Bookshops Limited 1921), available at http://www.marxists.org/archive/kautsky/1921/georgia/ch05.htm.

13 Z. Avalishvili, Georgian Independence in the International Politics in 1918-1920, at 281 (Mkhedan 2011) (1924).

14 Id. at 260.

15 Social-democratic orientation parties may have been in coalitions together with other parties (e.g. in Great Britain, with the Liberal Party), but Georgia’s experience was novel in that the government was solely composed of one party—Georgian social democrats.

16 Karl Kautsky, Georgia: A Social-Democratic Peasant Republic—Impressions and Observations, Chapter IX (H.J. Stenning Trans., International Bookshops Limited 1921), available at http://www.marxists.org/archive/kautsky/1921/georgia/ch05.htm.

17 Out of 505,000 constituents, Bolsheviks received only 800 votes. See Report of Georgian Constituent Assembly of 11 April 1919, at 31.

18 For discussions of this issue, see P. Sakvarelidze, Georgian Republic, Feb. 4; see also N. Zhordania, Remarks at the Tbilisi Party Meeting: Social Democracy and Organization of Georgian State, at 14-17 (Aug. 4, 1918).

19 Giorgi Gvazava, Basic Principles of Constitutional Right 97 (1920).

20 Id. at 76.

21 K.D. Mikeladze, Constitution of Democratic State and Parliamentary Republic, Some Considerations on Elaboration of Georgian Constitution 47 (1918).

22 Karl Kautsky, Georgia: A Social-Democratic Peasant Republic—Impressions and Observations, Chapter XII, The Bolshevist Invasion (H.J. Stenning trans., International Bookshops Limited 1924), available at http://www.marxists.org/archive/kautsky/1921/georgia/ch08.htm.

23 Z. Avalishvili, Independence of Georgia During 1918-1920 International Politics 351-360 (Mkhedari 2011) (1924).

24 On the whole, in February-March of 1921, the Russian red army, which consisted of four military corps, simultaneously unleashed an attack in five directions. They dealt two main blows on Georgia from the East (Azerbaijan) and the South-East (Armenia); the other three attacks were launched from the North—from the mountains of Caucasus, through the Dariali and Mamison mountain ranges, and by occupying Racha and Tskhinvali regions and invading Abkhazia from the Black Sea side.

25 Noe Zhordania, Times, Mar. 21, 1922.

26 Walter Elliott, a famous Scottish politician, was ironically criticizing R. McDonald, the Prime Minister and foreign affairs minister of that time because, although McDonald knew the situation in Georgia and was one of the first advocates of Georgia’s independence and defense of the country against Russian aggression at the beginning of twenties, as leader of the government, McDonald preferred to recognize Soviet Russia and be silent on the Georgian issue. See Walter Elliott, Georgia and Soviets, Letters to Editors, 27, 09, 1924.

27 George Papuashvili, Presidential System in the Post-Soviet Countries: Georgian Example, Review of Georgian Law, third quarter, at 22 (1999).

28 In 1992-1995 the law on the “State Authority” was active, which, to fill in the vacuum, was temporarily considered as the so-called “minor constitution.”

29 The first version of the Constitution adopted in 1995 referred to “[t]he basic principles of the 1921 constitution . . . .”

30 Noe Zhordania, Social-democracy and the State Organization of Georgia 32 (1918).